A Quiet Stand

A Quiet Stand

book review by Paul Hunter

Perhaps we cannot raise the winds. But each of us can put up the sail, so that when the wind comes we can catch it. – E. F. Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful: a Study of Economics as if People Mattered, 1973

The environmental debate has been raging for half my lifetime now, though the jury is no longer out, and hasn’t been for over twenty years. Skirmishes and battles have been waged, with condescension on both sides, with scoffing and denial on the one hand, and increasing depression and bitterness on the other. There have been escalations and casualties on both sides, though on the losing side — which we tremble to think is mostly the side of life — there has also been despair.

Those scientists entitled to an informed opinion have with rare exceptions agreed that climate change is real, serious, and largely man-made. It threatens most species, a stable environment, and the complex dance of interactions of life as we know it. All around us appears evidence of accelerating change. Records for rainfall, drought, heat, cold and violent weather events are now routinely broken season by season, year by year. This past summer a piece of fossil ice the size of Delaware broke off of Antarctica in the middle of its winter, dwindling to nothing drifting north. The only real question for a generation has been What are we going to do about it.

Not What do we wish could be done, not What will the powers-that-be do, but down at a personal level, prepared or not, What is each of us going to do. My son expects social collapse, rioting and looting, and has a survival kit he calls his bug-out bag, prepared to deploy like an earthbound parachute. The headlines of the past thirty years have long let us know that we cannot expect help from corporate entities, whose CEOs plead their defense of stockholders’ investments and the bottom line, over the health of the customer and the environment. No corporation can accept a smaller profit or take a step back from the brink, in the interest of a commons (which includes the atmosphere, climate, watersheds, resources, and the myriad other species alongside us) which either belongs to no one but itself, or else to all of us. Most of us have long heard about “the Tragedy of the Commons,” chillingly described by Garret Hardin in his 1968 essay, but most have no eye or stomach for its slow-motion disasters, much less the ability to imagine a cure. And elected officials at the national level are so abundantly funded and successfully lobbied that most big industries get to write the legislation and nominate the officials that supposedly regulate them. Sure, studies are commissioned, only to be filed, shelved, forgotten. The fox is in charge of the henhouse, and guess what’s for dinner.

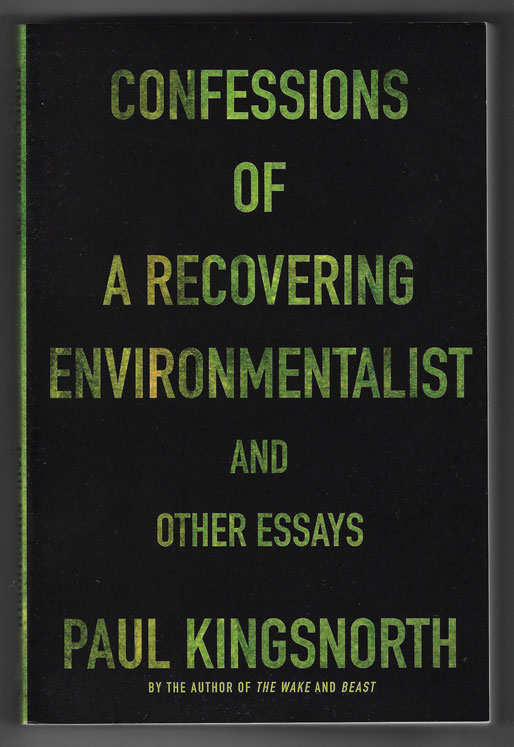

Maybe it’s time to see what there is still to be done, what lessons can be learned from the perspective of someone who has manned the environmental barricades for most of his adult life. Paul Kingsnorth is a British environmental activist and writer now in his midforties, still a young man, whose new book, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist and Other Essays (Faber & Faber / Graywolf Press, 2017, $16) leads us on a journey through his efforts in and around the halls of power, only to arrive with him at a dead end.

Burnout is common to idealists who invest deeply in their dreams. It is easy to overreach, and promise more than you have to give. Then too there is that tempered hidden anchor called hope, the mountain climber’s friend driven into cracks to belay and secure him as he goes, which still may fail first or last. So following the story that underlies these essays it is not hard to see how, as Kingsnorth says, finding himself increasingly mired in endless meetings with corporate spokesmen paid to resist him, enough futile effort might lead to despair. We are, after all, running out of time and breathing room, and can be driven mad by the smug resistance of those set against us for a fee.

Kingsnorth presents what he sees in blunt terms, and takes it personally. As he says:

Since my birth (1972), Homo sapiens sapiens has managed to kill off between a quarter and a third of all the world’s wild — i.e. nonhuman — life. This bald figure takes in 25 per cent of all land-based species, 28 per cent of marine species and 29 per cent of freshwater species. We’ve wiped out 35 per cent of the planet’s mangrove swamps and 20 per cent of its coral, over a quarter of all remaining Arctic wildlife and 600,000 square kilometers of Amazon forest. Extinction rates are currently between a hundred and a thousand times higher than they would likely be were humans not around. (85-86)

Given these losses in the past 40 years, in this report of a gasping, foundering planet there still is something to be said for how scientists work, for their admirable abundance of caution when setting forth the results of their research. Unlike politicians and corporate executives, most scientists are not addicted to tootling their own horns, or saying I told you so. But one might wish they spoke with a louder voice about such pressing matters, pumping up the volume. One might even want to hear them shout.

But Kingsnorth is no scientist, so his book documents the quest of a young man, like many a bright young person these days, stuck in a dilemma like quicksand, seeking to ground himself. Touch bottom, then reach up. Asking what is worth spending his life on, what is worth his attention, with his and his family’s and so many other lives at stake.

Kingsnorth points to a deeper malaise, to how the environmental movement itself has been co-opted, with the choices deliberately complicated, never either-or. In effect one can enjoy his tree-hugging impulses as long as they don’t interfere with a comfortable and entitled consumer lifestyle and its attendant corporate profits. He even dismisses the term sustainability as “a plastic word,” a mere manipulation to make us feel better, a way of keeping the global economic system and Industrial Agriculture and the consumer society firmly in place, spreading a grownup blanket of concern over some chilly realities, so we can get back to sleep.

It is not just a cautionary tale that Kingsnorth attempts to make out of a personal nightmare. Halfway though his journey he turns to buy a remote patch of wild land in the west of Ireland. There on two and a half acres he plants an orchard, a garden and a stand of fast-growing trees that will be harvested to feed his woodstove, while luring back the butterflies and birds. There he grubs out a living with his wife and two young children, there he finds an almost giddy joy in building and using a composting toilet, there he disconnects in every way he can, and takes a quiet kind of stand entirely new to him.

By now you might start to wonder what this review is doing in this magazine, although Paul Kingsnorth’s decision and recent actions should be familiar to readers of SFJ. This young man’s personal response answering his personal despair mirrors the grounded rural life Lynn Miller has been living, espousing and supporting in this magazine for over forty years. The implications are plain. It is eminently sane to find one’s place and commit to it, to take one’s life in both hands planting, weeding, harvesting. To feed one’s family, one’s neighbors, and oneself. To build and sustain community. To sharpen one’s own tools, keep the scale deliberately small, human and personal, to avoid relying on fossil fuels and expensive industrial inputs, to let nature help one make a modest living without self-congratulation or apology. Paul Kingsnorth’s way also mirrors Lynn Miller’s in how he senses that our civilization has been failing by repeating the wrong stories to itself. Like the editor of this magazine, Kingsnorth also believes that art has the chance to save us, if it will invent new stories, new poems and novels, songs and paintings and plays that value different ways of being and doing, that recall and espouse a vital connection with nature. In that notion he also mirrors Lynn Miller’s work painting and writing, sensing a deeper purpose, refreshment and renewal in the arts, that give us healthier and more honest ways of acknowledging our place in the scheme of things.

In his wide-ranging exploration there are four issues Kingsnorth addresses that may be of special interest to SFJ readers: Species, Science, Scale and Story. Considering Species, first there is the question of Nature, which is where do we fit into the teeming dance of life in all its forms. For most of our history humans have been told by their religious leaders and philosophers that we stand apart from nature, and that, in the biblical phrase, we have been given dominion over the rest of the living world, to do with as we please. Religious leaders try to recast this as man’s duty, an issue of stewardship, but that role is quickly muddied by the taint of profit, and how that profit seen as a mark of God’s favor too easily becomes an excuse for self-congratulation as we eat and pollute our way to heaven. We might well ask, do we need the rest of life to make us whole, or can we dismiss and destroy the myriad other lives in our quest for comfort and profit? What if we are only one more wild animal incapable of domestication, of being permanently bent to another’s will, and in that lies our salvation? The bedrock sanity for Kingsnorth would seem to be to accept one’s kinship with all other life forms, and attempt to harm no others by one’s living and doing.

The second issue, Science, is really mostly that of applied science, or technology. Which in recent years has been raised to a power that surrounds and consumes us. It is what Kevin Kelly in his book What Technology Wants has labeled the technium, which is a gathered and linked quasi-reality that has Kingsnorth wary, paying close attention to the internet, the smart phone, and a growing cyber-replacement of the faulty and flawed natural world:

“I think there is something bigger than us, rearranging itself around us now like a prison. It’s a prison we don’t seem to want to escape from, because there’s so much fun to be had in it; and anyway if we did want to escape we couldn’t, so why bother trying?” (pg 247)

There is a further threat he notes in a gathering of thinkers around Stewart Brand, whose answer to most environmental concerns is a technocratic solution. His slogan is, “We have become as gods, so we might as well get good at it.” This is where gene-splicing and GMO crops and other technical solutions meet with their greatest enthusiasm — and, to Kingsnorth, their nearest approach to madness. One example he offers concerns the problem of “colony collapse disorder” with honeybees, traced to the use of neonicotinoids. Rather than ban this pesticide as has been done in France, he notes that Harvard University is working on a ‘Robobees’ project — using nanotechnology to create tiny bots run by the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, with the ambition to replicate and replace an essential player in the reproductive dance of the natural world. It need hardly be noted that the project dismisses the obvious solution (which might impact the bottom line of the Bayer Corporation and its competitors) and seeks to develop an artificial mechanical replacement for the honeybee, at untold cost to plant and insect life, not to mention hidden and unpaid energy costs. But hey, robobees might come in handy should we want to colonize planets with atmospheres too hot or cold or poisonous for humans, never mind for the rest of nature.

Considering that third issue, Scale, a despairing Kingsnorth sees no answer to what he calls “the crisis of Bigness.” It’s not just the efficiencies of scale growing ever larger, but the irresistible exercise of corporate power that recognizes no other motive besides short-term profit, no trajectory but limitless growth. Ambition itself has soured. Successful start-ups these days mostly hope to be noticed by the handful of global players while they’re still relatively overvalued, and can be gobbled up. It may be that Bigness tips him over the edge. In the face of the endless and inappropriate accretion that is scale he has no strategy at last, but to step away.

Since his moment of resignation and release, what Kingsnorth has been doing hand-in-hand with his subsistence living, scythe-sharpening and mowing, is called the Dark Mountain Project, a website (www.darkmountain.net) and a journal that not only makes use of his arts as poet, essayist and novelist, but engages in an ongoing conversation with artists who are likewise stymied and seeking new ways forward. Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine have written a manifesto they call “Uncivilization,” which ends the book, and upends much of what we think of as a civilized and appropriate human life and responses.

Kingsnorth’s recent work moves away from tackling many of the big issues, that have been jettisoned as he takes a more personal and provisional stand. For instance, the book says nothing about population control, though a mounting global population can’t help but exacerbate every problem the earth faces. Increasing claims on resources that can’t be replaced and won’t be rationed except by the pricing of the marketplace just means worsening international tensions, and an accelerating race to the bottom that has no winners in the long run. Mounting inequality in the ownership of land and control of vital resources is yet another problem making environmental problems intractable. And as for the wealthy in their cocoons, living off of amassed wealth without working, spending by whim, addicted to the shopping spree, the comfort zone and restless global travel — well, Kingsnorth has no time to consider such inanities. The view is often dark and the hour is late.

Still, he does steer the reader toward the bedrock of some real solutions. For instance, how market capitalism utterly fails to contain environmental problems. He points out how in 1997 a team of economists calculated how much value was contributed to the global economy by nature, as opposed to human effort. Their results: “For every US dollar’s worth of goods and services consumed by humans each year, about 75 cents are provided free of charge by the Earth’s ecosystems.” (36) If we believe the true costs are factored into the price of, say, fossil fuels or industrial feedlot beef, we are only deluding ourselves and colluding in corporate welfare. The public always picks up the tab for industrial pollution dumped on lands and waters that supposedly belong to us all — those hidden costs that are never factored into optimistic estimates of economic growth. And species loss allows no calculations that make sense in a bottom-line economics approach to value.

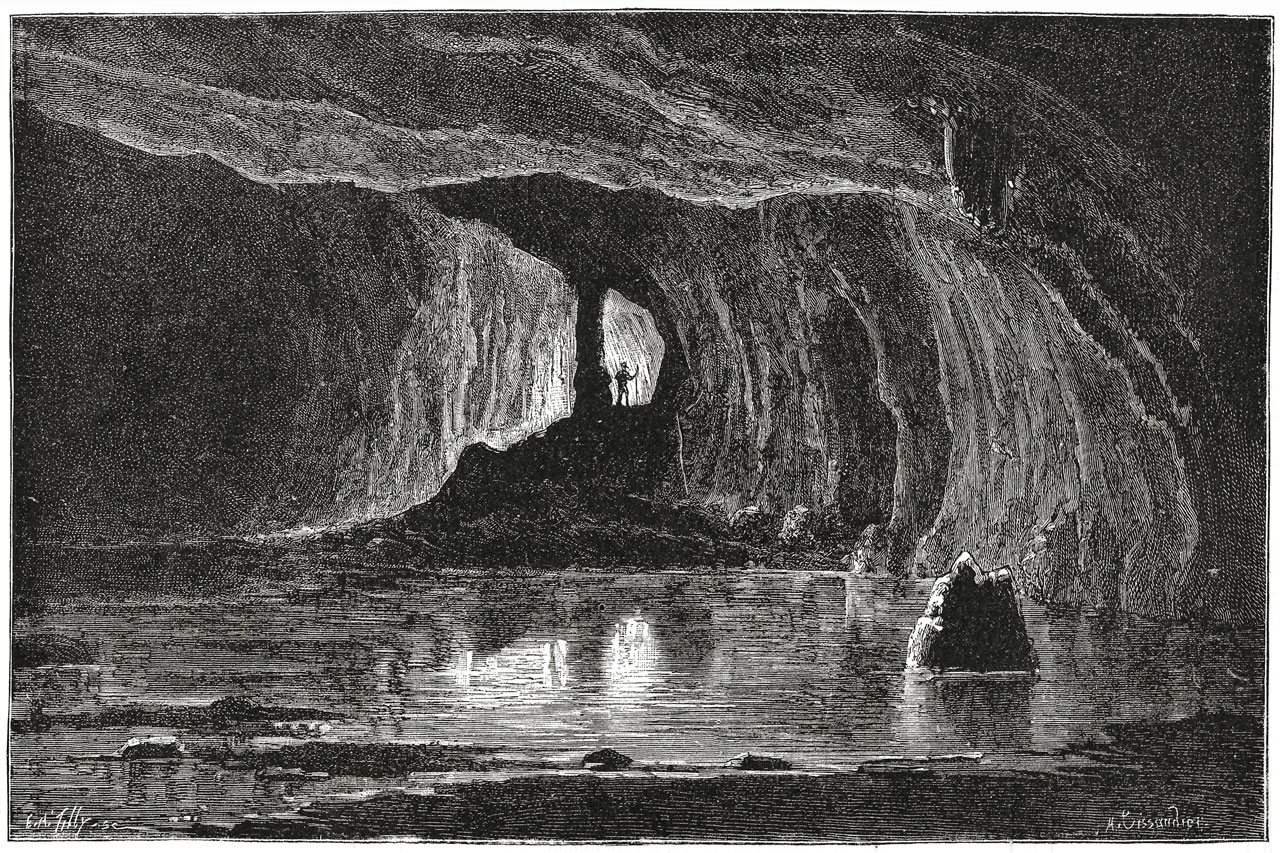

On a personal note, Kingsnorth’s description of his visit to Niaux Cave in the French Pyrenees did touch the core of the human mystery for me. The people classified by prehistoric anthropologists as ‘Magdalenians’ visited the cave about 15,000 years ago. They did not live in these deep caves, did not depict the animals they routinely hunted and ate, which were mostly reindeer. Unlike some other cave paintings, here are no hunting scenes, no signs of violence, no humans, no hunters and no weapons at all. As Kingsnorth says, “These are not triumphant paintings of vanquished prey,” but instead vivid life studies. Beautifully and accurately rendered, the great mammals float and hover on the walls — bison, mammoth and ibex — without their settings in nature, without a touch to suggest grass, plants, trees. In places the artist’s palette of paints and drawing materials still lie at the foot of the walls. Kingsnorth wonders if these weren’t “depictions of, or aids to, shamanic journeys: visits to another world in which humans become animals and animals become humans.” (157) His awe is palpable. One can’t help but wonder if those animals painted and drawn in the region weren’t already extinct. The mystery only deepens as one looks.

And what do Kingsnorth’s feelings about nature and such arts born of nature amount to?

“They are the result of me being an animal in a world of beauty, depth and complexity, and feeling that this external abundance is a part of my internal life. They are a result of me feeling, assuming, knowing that the Earth is not a machine; that all is alive, still. They are a result of me feeling small in the face of all this, and being grateful for the humility this forces on me, even if sometimes it may be against my will.” (172)

Finally we arrive at the last key to the book, what Kingsnorth means by the word Story, and how he uses it. Since he holds out only this slim hope, that we have been telling ourselves the wrong stories. He says “A nation is a story that a people chooses to tell about itself.” (203) In The Eight Principles of Uncivilisation that end the book, he says:

“We believe that the roots of these crises (the current social, economic and ecological unraveling) lie in the stories we have been telling ourselves. We intend to challenge the stories that underpin our civilisation: the myth of progress, the myth of human centrality, and the myth of our separation from ‘nature.’ These myths are more dangerous for the fact that we have forgotten they are myths.”

“We will reassert the role of storytelling as more than mere entertainment. It is through stories that we weave reality.” (283)

This is a bold thought, and he means it. No matter how difficult, he vows to celebrate writing and art that are “grounded in a sense of place and of time.” The SFJ reader in particular may applaud his comment that our arts have been dominated for too long “by those who inhabit the cosmopolitan citadels.” (284) He wants stories of the woods and fields, the waters and wilds, of the creatures that share this world with us.

New stories for these restless and desperate times. This is more than a thoughtful British take on a set of problems Americans have treated as uniquely theirs — or as everyone else’s but theirs. The American reader may find many of Kingsnorth’s views unduly gloomy, but given a fair hearing, they may ultimately prove arresting and bracing. He means to stop us in our tracks, because there is something else at work here. The book “goes a progress,” as the gravedigger in Hamlet phrases it — that is, it takes a measured and formal journey that may seem predictable, but often is anything but. Here is a young man who has had a change of heart, and a change of life, and the sequence of his essays tells the tale. This, I kept telling myself, is what it’s like to be grown up and wide awake, facing the consequences of human sleepwalking for much of human history, finally facing the choices and actions each of us must make. Either that, or go back to sleep, accepting that what comes will surely be a ruder wakening.

Anything that we can destroy, but are unable to make is, in a sense, sacred, and all our ‘explanations’ of it do not explain anything. – E. F. Schumacher, A Guide For the Perplexed, 1977