Farm Sheep Raising for Beginners

Farm Sheep Raising for Beginners

U.S. Department of Agriculture Farmers’ Bulletin No. 840, 1934

by F.R. Marshall and R.B. Millin, Animal Husbandry Division, Bureau of Animal Industry.

revised by D.A. Spencer, Senior Animal Husbandman, and C.G. Potts, Animal Husbandman, Animal Husbandry Division, Bureau of Animal Industry.

One indicator of the mercurial swings in agricultural production in North America has been sheep. Time was, not so very long ago, when we were a major producer of these multi-purpose animals. Tens of thousands of sheep have been taken off the roster in the US and Canada as consumption of both wool and lamb declined. As has been evidenced by the fine reporting our own Charles Capaldi has brought to the Journal on the subject of wool today, many changes have occurred and will continue to occur. It is this writer’s contention that sheep will be returning in large numbers to this continent and primarily because they do fit so well into the new diversified family farm. The information which follows (part two will appear in the next SFJ) offers up a view of how this important industry was approached many years ago. Most of this material is applicable today. We hope you will find value here in the history and methods and, as always, look to additional sources (such as the fine current books we offer through the Journal’s book service), for new innovations and ideas. LRM

SECTIONAL POSSIBILITIES FOR SHEEP PRODUCTION

In the section of the United States east of the one-hundredth meridian, sheep are usually kept in small farm flocks and raised almost entirely in connection with other agricultural enterprises. Sheep raisers in this area have a material advantage over those in the western half of the country in that they are located nearer the largest consuming centers of lamb, and therefore have lower transportation charges as well as being able to place their lambs on market in a shorter period of time. At least half of the lamb that is eaten in the United States goes to consumers in those States lying north of the Potomac River and east of the State of Ohio. Probably three-fourths of the total amount of lamb eaten is consumed in the States east of the Mississippi River.

Sheep raising has been carried on in New England since the days when the region was first settled, and at one time New England ranked first in the United States in the production of sheep and of wool. Although flocks of sheep in the Northeastern States were much reduced in numbers after new lands in the West began to be opened up and brought into the agricultural production system of the Nation, New England is still well adapted to sheep raising, and it retains its material advantage over other regions of being nearest the centers of population and of the consumption of lamb. The dairy industry has been the greatest competitor of the sheep industry in New England because of the large outlet for market milk in that region.

Throughout the entire length of the Appalachian Mountain Range in the States of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, there are to be found large areas of country well suited for the raising of sheep. Much of this mountain region, together with adjacent sections in the States of Kentucky and Tennessee, ranks high in the production of high-quality early lambs destined to be sold on the eastern markets.

In the hillier sections of northern Arkansas and southern Missouri there are large areas of comparatively cheap lands on which sheep can be raised at relatively low costs. Dogs and other predatory animals, however, occasionally ravage the flocks which are kept in these sections, and the effect of their attacks has been to retard the development of the sheep-raising industry to some extent.

Cut-over timber lands in the States of Michigan and Wisconsin offer excellent summer grazing for sheep, but the winter seasons in that territory are long and severe. The result is that the cost of feeding the animals during the winter months greatly reduced the amount of profit which it is possible to realize from a farm flock.

Sheep raising is not necessarily confined to regions where there are large tracts of cheap land unsuitable for other agricultural enterprises. In the Corn Belt, where lands are higher in price than those which have been enumerated, there has been worked out a profitable system of sheep raising in which both permanent pasture and forage crops are utilized. When this system is followed in connection with other farm operations it provides for a more effective utilization of labor and feed supplies on the farm, and thereby increases the farm income.

Sheep can also be kept to advantage on considerable numbers of irrigated farms in the West. On such farms the irrigation ditches, as well as the forage crops produced, provide a portion of the summer pasture for the sheep, if not all of it. Harvested crops, especially alfalfa, that are produced in most irrigated sections, will provide excellent winter feed for sheep. By pasturing sheep on such crops during the summer months much of the expenses of harvesting the crops will be eliminated. It is also true that the cost of marketing such crops as grain and hay in the form of lamb and wool is much lower than would be the cost of marketing the same crops unfed. The use of crops for pasture provides for the flock owner an opportunity to rotate the feeding grounds of his sheep and in this fashion to reduce the losses from stomach worms which usually infest heavily stocked pastures and attack sheep which are pastured there.

REQUIREMENTS FOR SHEEP RAISING

SOIL AND CLIMATE

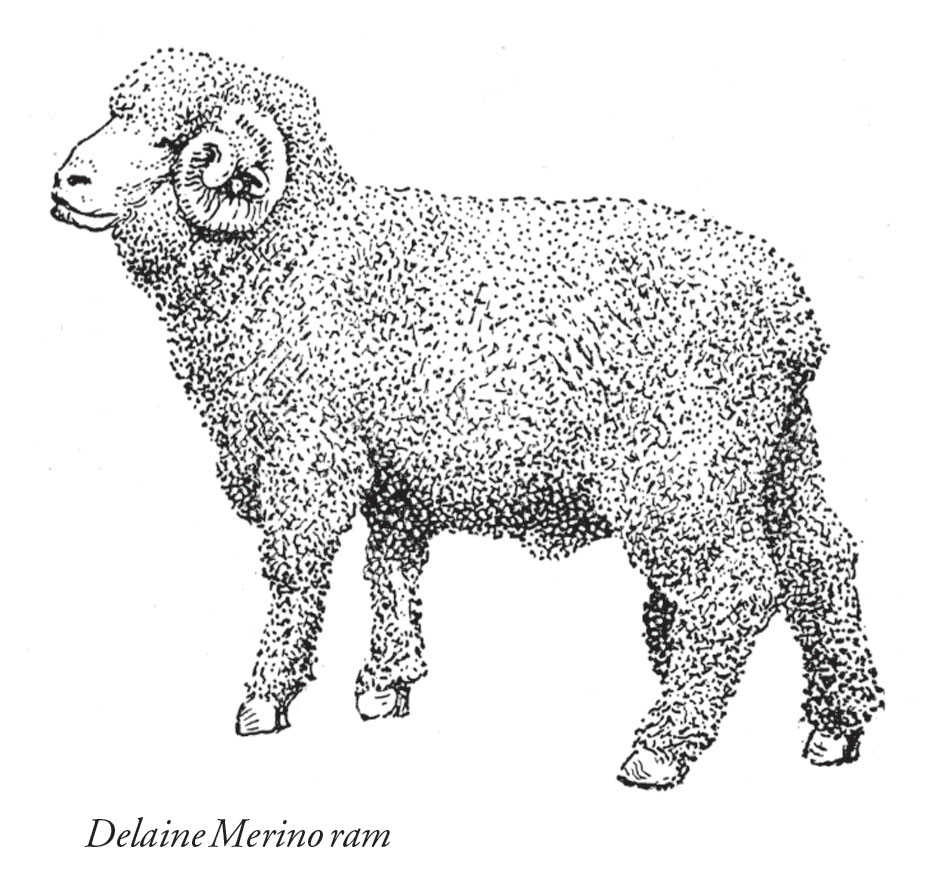

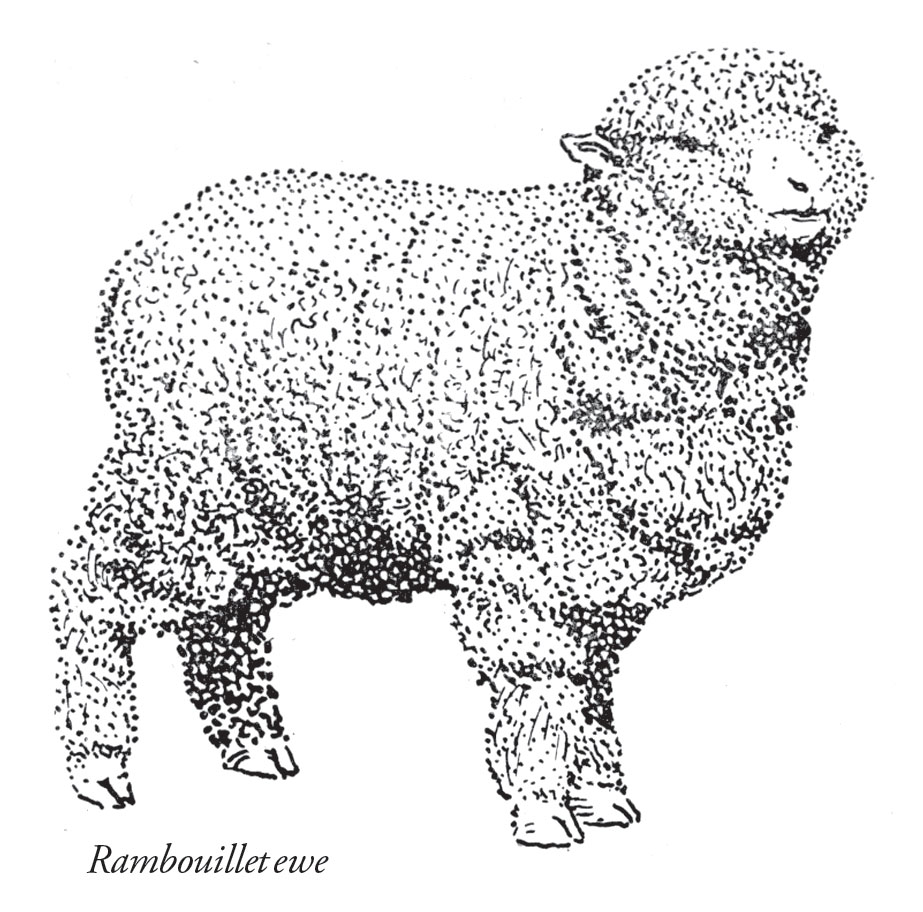

Sheep naturally inhabit areas that are high and dry. The animals, however, will thrive on any land except that which is wet and swampy. The fine-wool breeds of sheep especially exhibit a preference for the lands that are drier, whereas there are one or two of the British breeds that are particularly adapted to the lowlands. The industry of raising sheep has been carried on with success in areas that have tropical temperatures with low rainfalls, but rearing the animals in regions of high temperatures and high rainfall has not been generally successful.

PASTURE AND FEED

It is the natural habit of sheep to graze over rather wide areas of land and to seek a variety of food plants. This habit particularly adapts these animals to being kept in large numbers on lands that have sparse vegetation or lands that furnish a wide variety of grasses or other plants. The sheep do better on grasses that are short and fine than they do on coarse or high feed. They will eat considerable quantities of brush, and when they are confined to small areas they will do a fair job of cleaning up land or when they are pastured wholly on land that produces nothing but brush, they can not be expected to prove very satisfactory in their production of good lambs or of good wool.

The cheapest and best feed for sheep is pasture such as that which has been described, or sown forage crops of cereals, rape, etc. Changing the grazing ground frequently is a practice that has been found necessary to the health and maximum thrift of the sheep when the pastures to which they are confined do not offer a wide range. This practice calls for fencing to be used in subdividing permanent pastures or for tight fencing around runs in which the sheep are to be kept. Sections of movable fencing may be used to a considerable extent in carrying sheep on smaller areas of forage crops.

It is seldom profitable to feed grain to sheep when good grazing is to be had for them. Under some conditions flocks can be kept in good condition and lambs can be raised to the marketing stage without the feeding of any grain. One hundred pounds of grain in a year for one ewe and her lambs is the maximum amount that it is likely to be profitable to feed under any conditions. The largest quantity of grain may be fed to ewes that are dropping their lambs before pasture is ready and to the lambs during the same period, but the feeding that is most economical and most likely to keep the flock in good condition is that which provides frequent changes of good pastures and grazing crops and winter rations mainly of good leguminous hays, with some succulent feeds, reserving what grain is to be used to feed in winter and after the lambs are born.

Silage or roots furnish cheap feed and are especially useful in keeping ewes in good condition during the winter. Too free use of roots for ewes in lamb is sometimes considered to increase the losses of young lambs, and the exclusive use of silage as a roughage has been shown to be unsafe, either for the ewes themselves or for the lambs to be dropped.

BUILDINGS AND FENCES

In any part of the United States the main essentials of sheep barns are dryness and freedom from drafts. Unless lambs are to be dropped in cold weather, no expense to provide warmth is necessary, as the buildings should seldom be closed. Protection from winter rains and heavy snowfalls is desirable, but the best results may be expected when ewes are allowed access to a dry bed in the open.

Fences to hold sheep should be of woven wire, boards, or rails. Barbed or smooth wire can not be used satisfactorily, though a 36-inch woven-wire fence at the ground with two or three strands of barbed wire above the mesh is commonly used.

LABOR

The amount of labor required to keep a farm flock in the condition necessary to insure maximum returns and lowest cost of production varies according to systems followed in different sections. In all cases the amount of labor is small in proportion to that required by other livestock products of equal value. Feeding the sheep in winter is light labor, and the manure need not ordinarily be removed from pens oftener than once in six weeks during the time the flock is housed.

However, sheep raising should not be engaged in with an idea that little attention is required. The wants of sheep are numerous and varied, and frequent attention is required to forestall conditions that will result in ill health or lack of thrift. With a large flock at lambing time frequent attendance day and night is necessary to avoid losses of ewes and young lambs. While their habits are quite different from those of other farm animals, sheep are an interesting study. Sheep management can be learned and understood by anyone who is willing to observe carefully and think and attend to the details as attention is required.

STARTING THE FLOCK

TIME TO START

Late summer or early fall is the most favorable time to make a start in sheep raising. Ewes can be procured more readily at this time, and when purchased can be kept on meadows, grain stubble fields, or late-sown forage crops to get them in good condition for breeding. Experience with the ewes through fall and winter will also render a beginner more capable of attending to them at lambing time. It is seldom possible to buy any considerable number of bred ewes at reasonable prices.

SELECTION OF STOCK

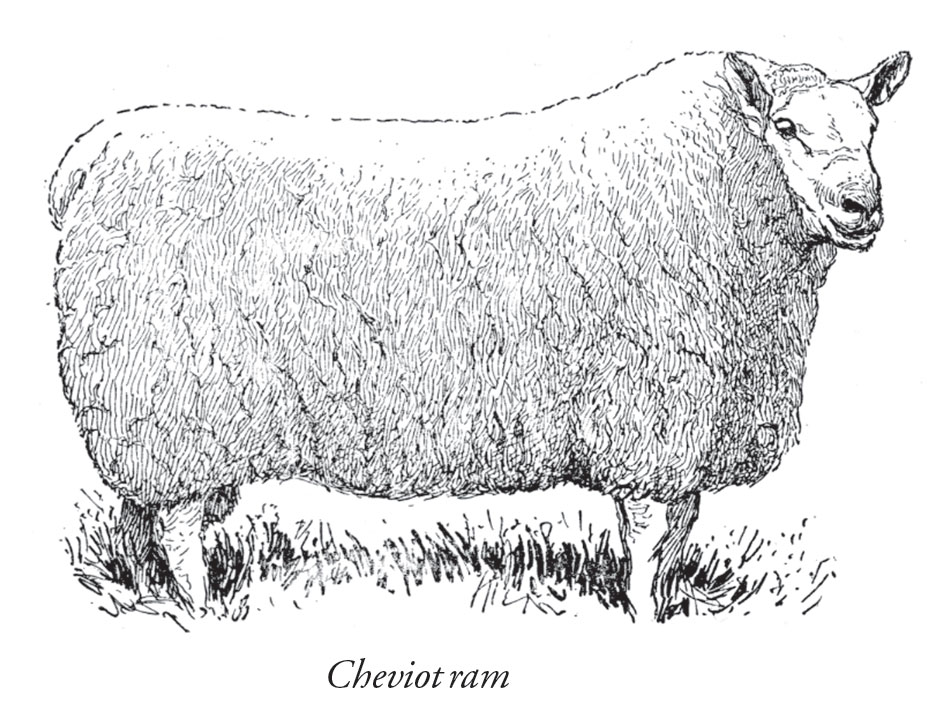

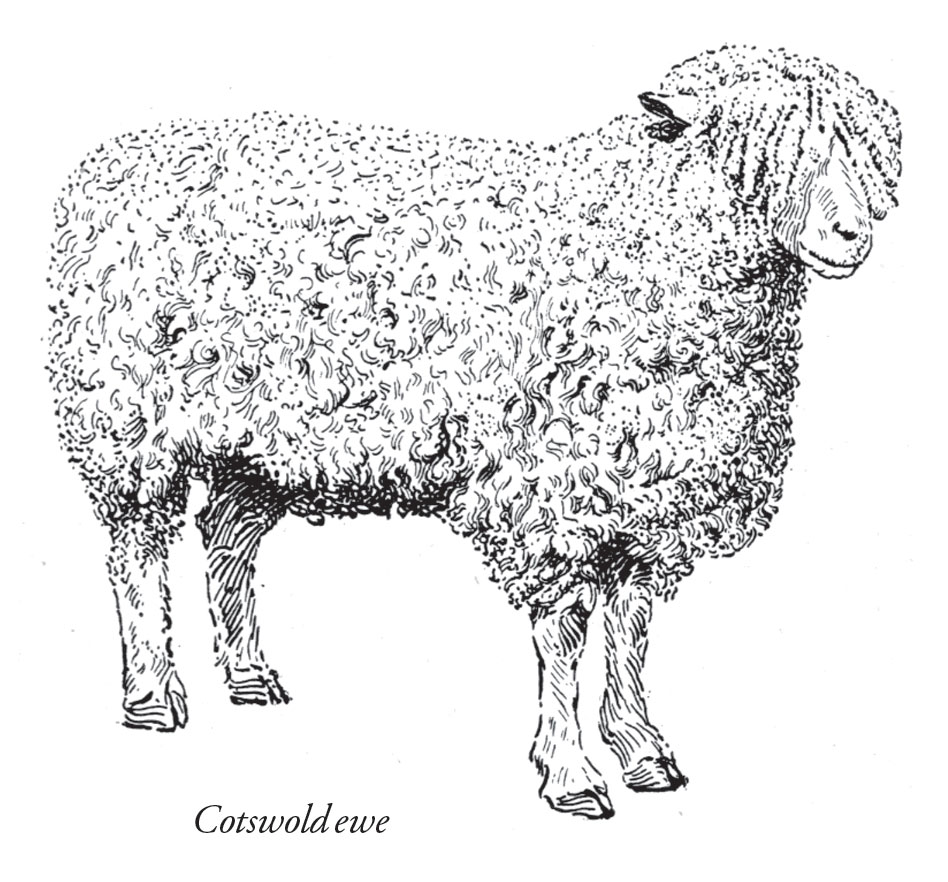

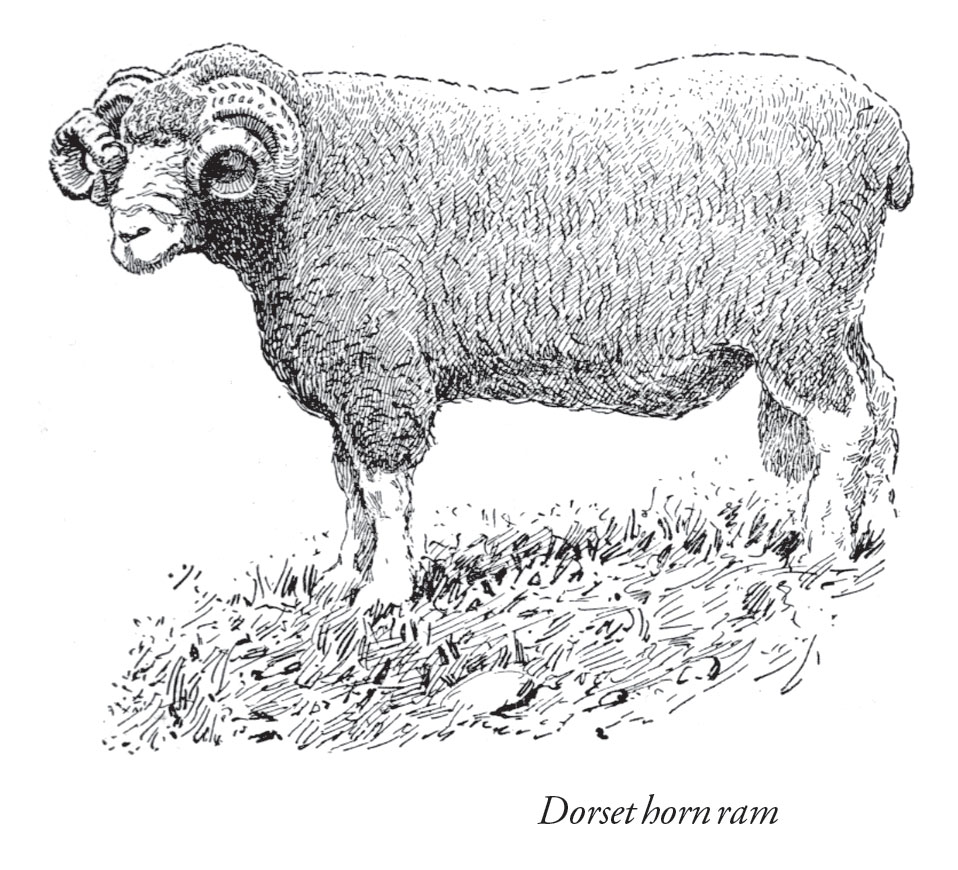

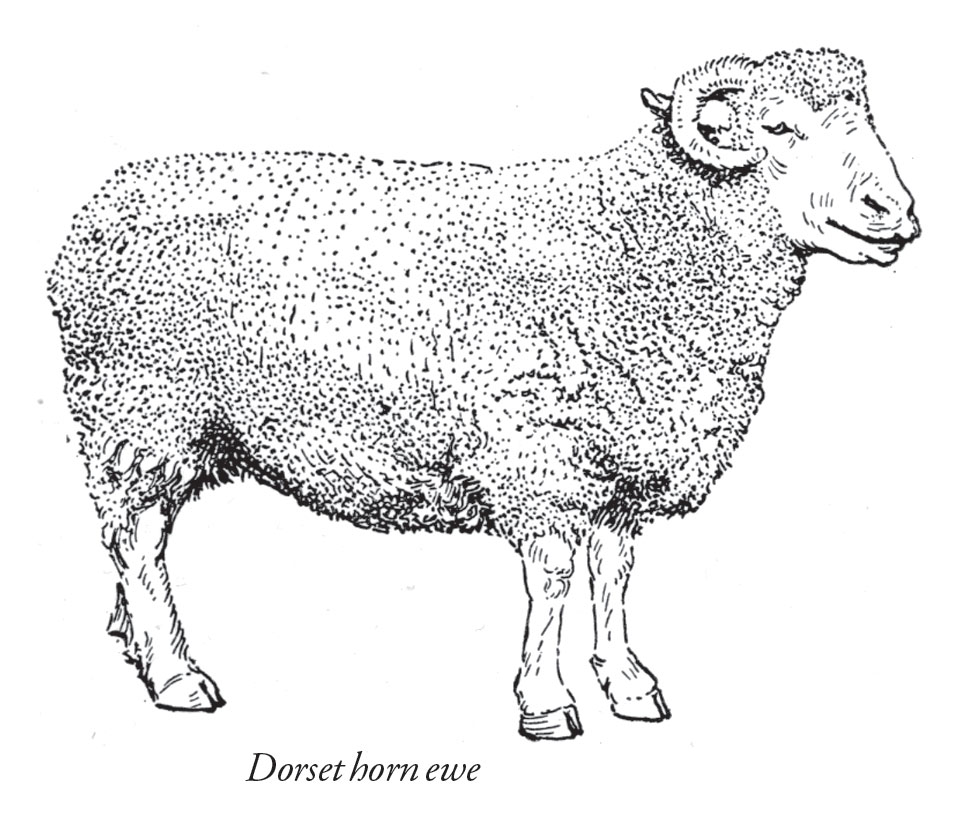

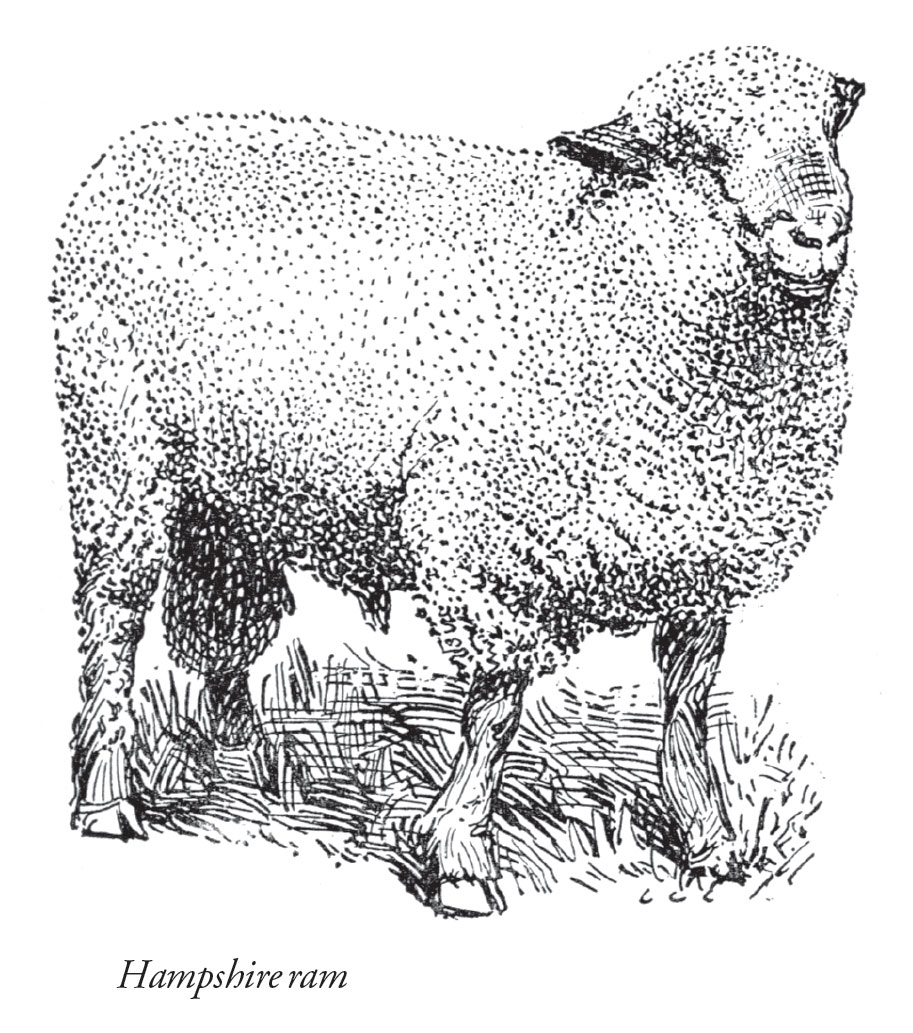

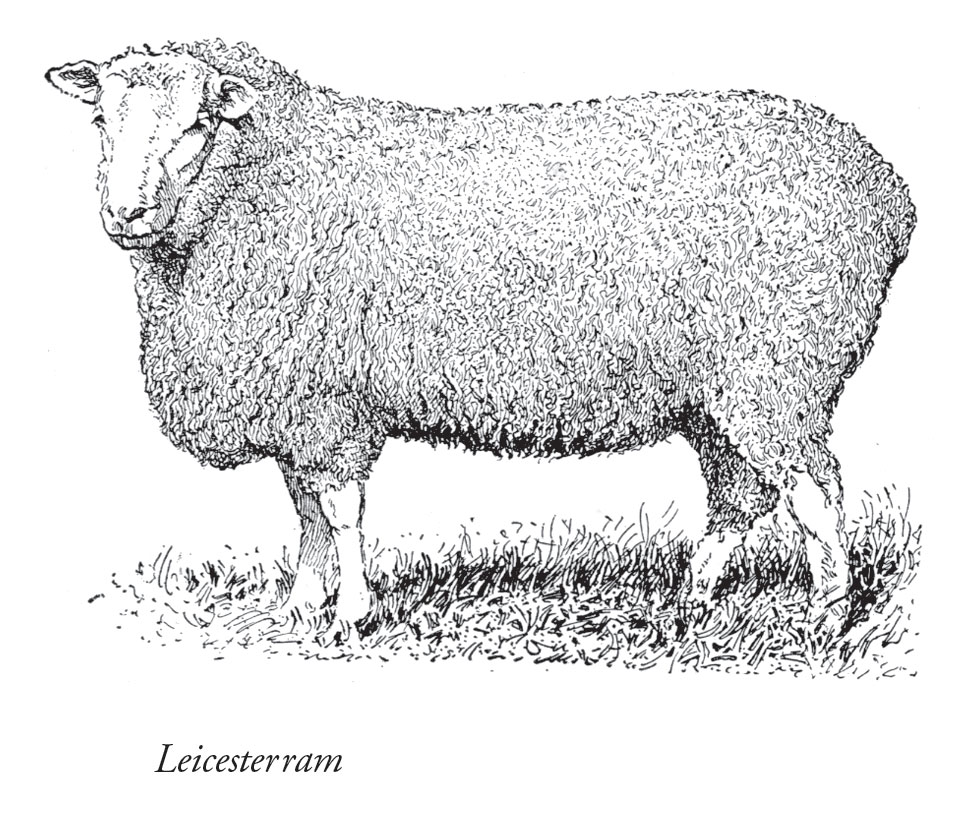

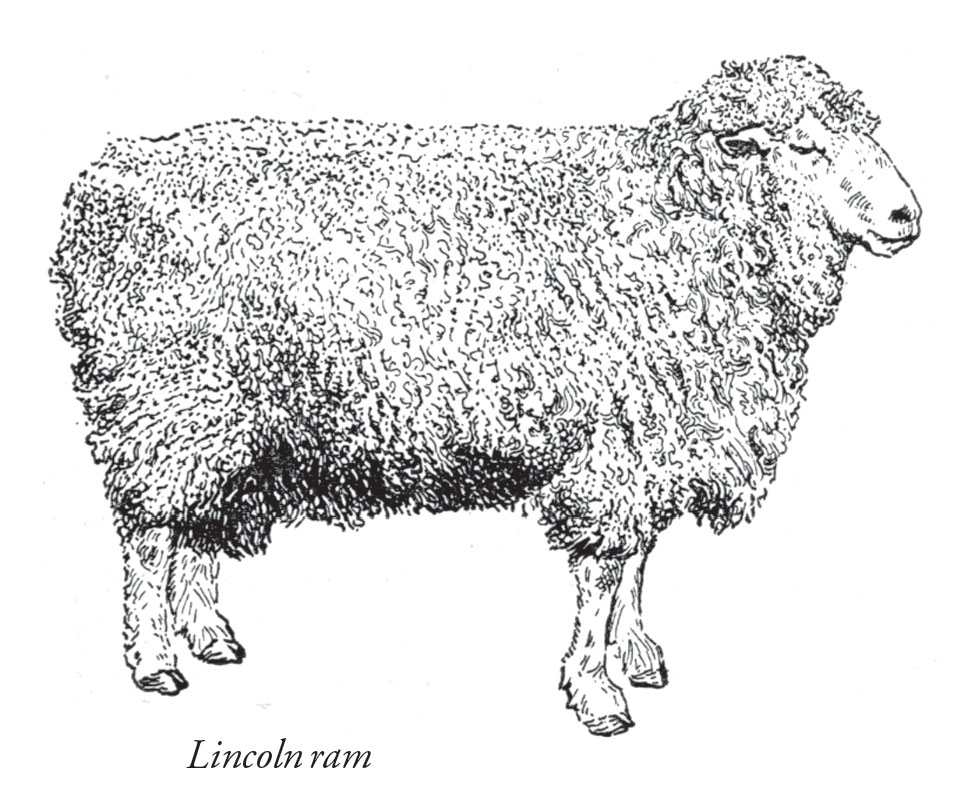

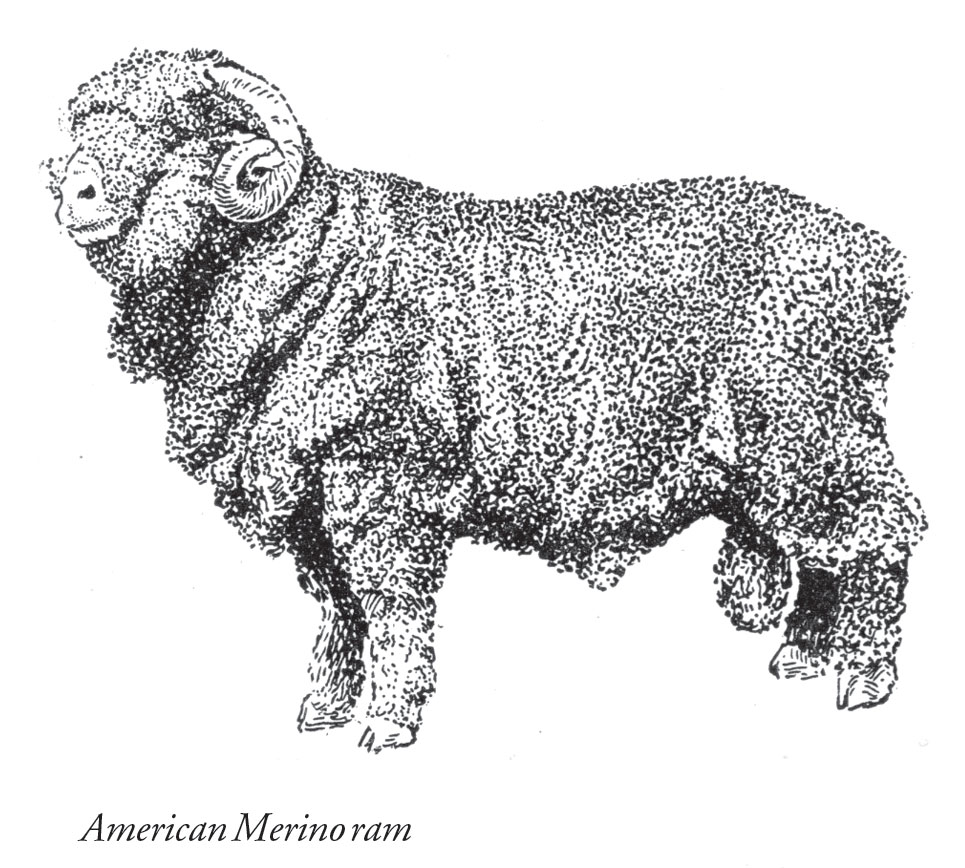

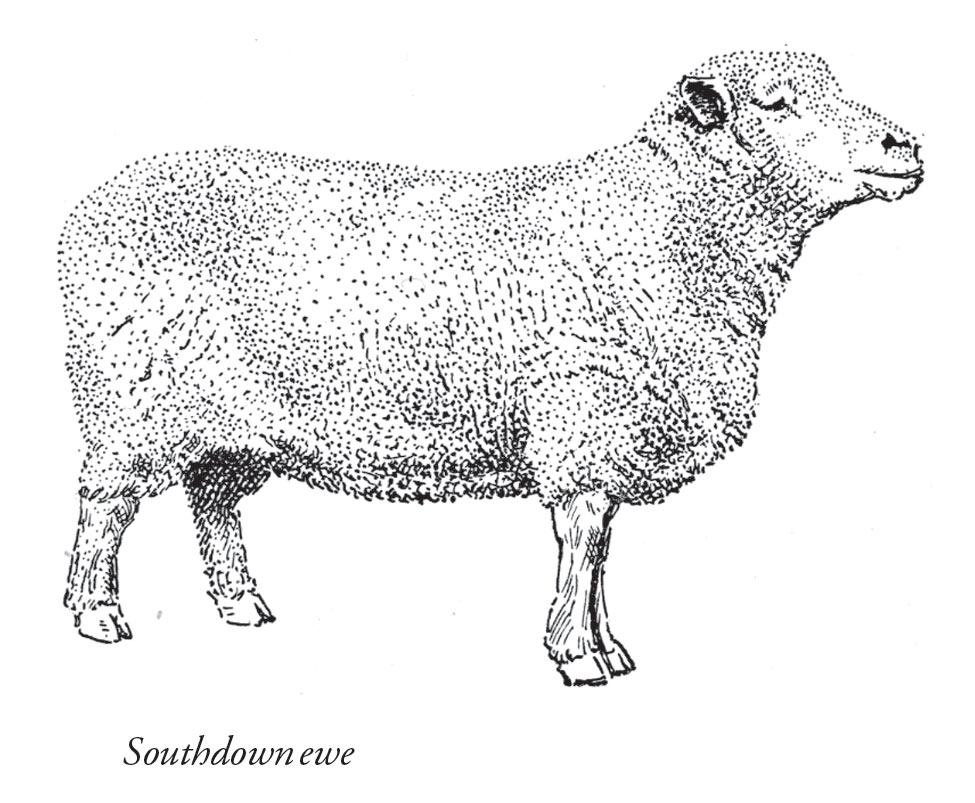

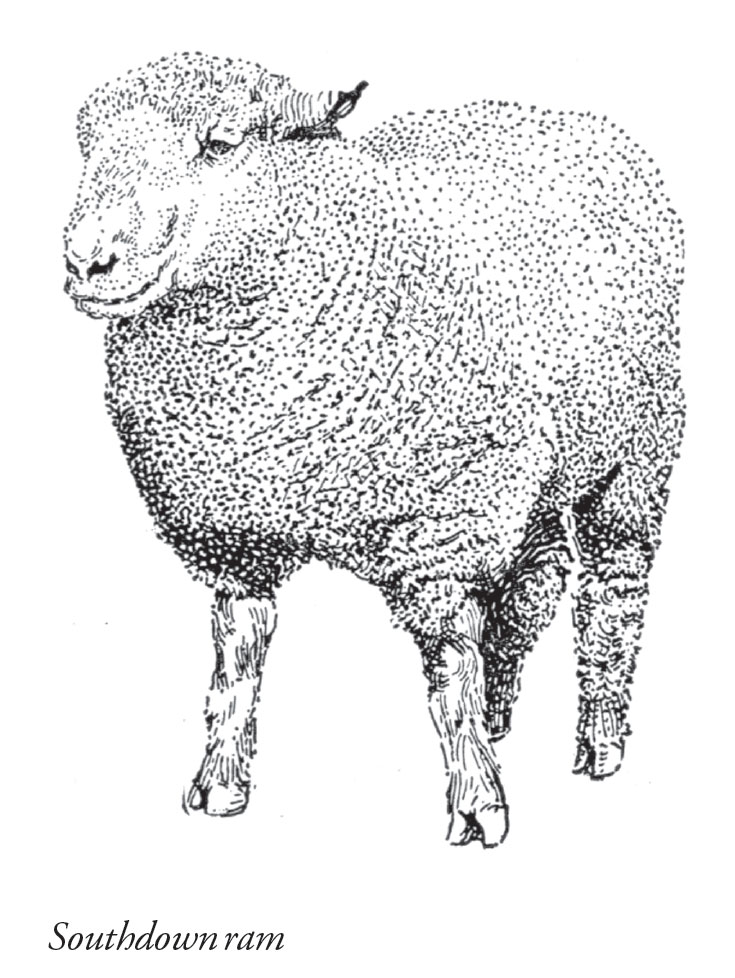

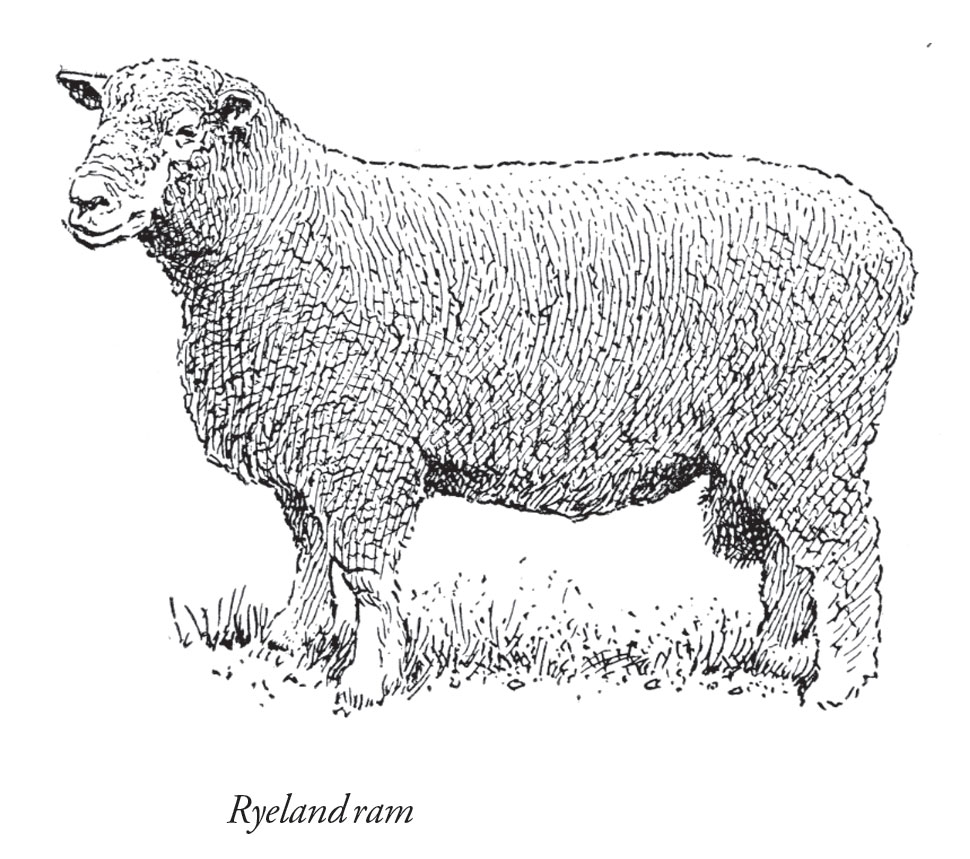

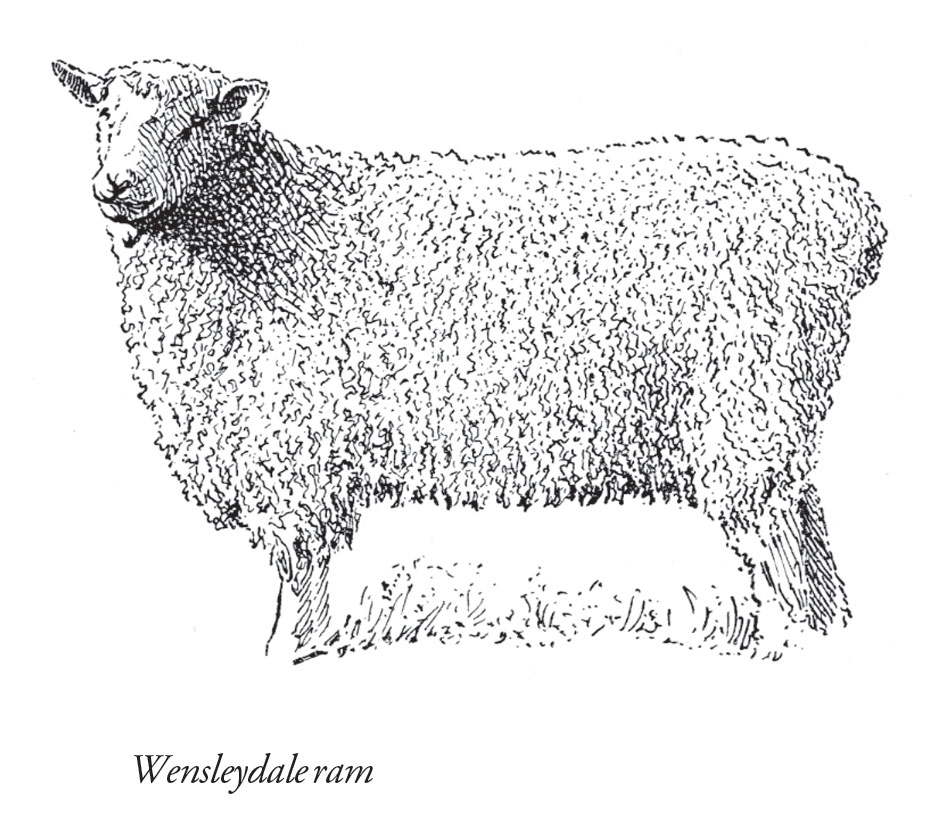

The inexperienced sheep raiser should begin with grade ewes of the best class available and a purebred ram. The raising of purebred stock and the selling of breeding rams can best be undertaken by persons experienced in sheep raising. The selection of the type and breed of sheep should be made by considering the class of pasture and feeds available and the general system of farming to be followed, along with the peculiarities of the breeds and the conditions and kind of feeding and management for which each has been especially developed.

It is highly advantageous for all, or a majority, of the farms in a neighborhood to keep the same breed of sheep, or at least to continue the use of rams of the same breed. After a decision has been made as to a suitable breed, the aim should be to obtain ewes that are individually good and that have as many crosses as possible of the breed selected. With such a foundation and the continuous use of good purebred rams of the same breed, the flock will make continuous improvement. In looking for ewes of desired types and breeding it will often be found impossible to get them near at home at a reasonable price. Ewes from the western ranges can be obtained directly from a stockyard market. For the most part the range ewes are of Merino breeding. First-cross ewe lambs and less often older stock bred on the range and sired by rams of the down or long-wool breeds are sometimes obtainable. These, or even the Merino ewes, furnish a foundation for the flock that can be quickly graded up by using rams of the breed preferred. The lambs from Merino ewes and mutton rams grow well and sell well if well cared for, but the yield is less than when ewes with some mutton blood are used. The sheep from the range are less often infested with internal parasites than are farm sheep, and in the large shipments there is opportunity for closer selection.

AGE OF EWES

Yearling or 2-year-old ewes are preferable to older stock. Ewes with “broken mouths” — that is, those that have lost some of their teeth as a result of age — can be purchased cheaper than younger ones, but are not good property for inexperienced sheep raisers.

Until a sheep is 4 years old its age can usually be told within a few months. The lambs have small, narrow teeth, known as milk teeth. At about 12 months of age the two center incisors are replaced by two large, broad, permanent teeth. At about 24 months two more large teeth appear, one on each side of the other pair. Another pair appears at 3 years of age, and the last, or corner teeth, come in at about the end of the fourth year, and the sheep then has a full mouth. Heavy or light feeding has considerable effect upon the exact time of appearance. After a sheep becomes 4 years old the exact age can only be estimated. As age advances, the adult teeth become shorter and the distance between them increases. The normal number of teeth may be retained until 8 or 9 years of age, but more often some are lost after the fifth year.

In buying ewes, particularly those from the range, it is desirable, when possible, to examine the udders to see that they are free from lumps that would prevent the ewes from being milkers. It is necessary to guard also against buying ewes that are useless as breeders because of the ends of the teats having been clipped off at shearing.

SIZE OF FLOCK

Persons wholly inexperienced with sheep will do well to limit the size of the flock at the start. A beginner can acquire experience quite rapidly with 8 or 10 ewes. It is very doubtful, however, whether anyone should make a start with sheep unless the arrangement of the farm and the plan of its operation allow the keeping of as many as 30 ewes, and in most cases 60 or more will be handled better and more economically than a very small flock. The number of ewe lambs that can be kept for breeding each year should be about one-half the number of breeding ewes. Old ewes usually should be discarded when 5 years old. When this is done and the poorest ewe lambs are sold a flock will ordinarily double in size in three years. After two seasons’ experience it will be a good plan to buy more ewes when good ones can be obtained at a fair price.

The economical disadvantage of a very small flock lies in the fact that the hours of labor are practically the same for a dozen or 20 ewes as for the larger flock. The fencing to allow desirable change of pastures or to give protection against dogs is about the same in either case, so that the overhead charges per ewe are much smaller in the case of the larger flock. Furthermore, the small flock on a farm having larger numbers of other animals is unlikely to receive the study and attention really needed or that would be given to one of the chief sources of the farm income.

MANAGEMENT AT BREEDING TIME

THE EWES

The period of gestation in sheep is 145 days. Ewes should be mated to drop their first lambs when about 24 months old. The first few cool nights in late summer or early autumn cause the ewes to come in heat, although some breeds come in heat at almost any time of the year. These periods in which the ewes will breed last from 1 to 3 days and recur at intervals of from 14 to 19 days. At the time the ewes are bred they should be gaining in weight. Feeding to produce this condition for breeding is commonly called “flushing.” The main purpose of flushing the ewes is to secure a larger lamb crop and to have the lambs dropped as near the same time as possible, but it also brings the ewes into good condition for the winter. To accomplish this the ewes are changed from scant to abundant pastures of timothy, bluegrass, or rape. Rank, watery, fall growths of clover are of little use for this, as they often bring the ewe in heat several times and are not particularly fattening. Often some grain is fed as a supplement to the pastures. Corn is not especially good for this, oats being much better. Pumpkins strewn over the fields are excellent. At this time any large locks of wool or dung tags about the tail should be removed.

THE RAM AT BREEDING TIME

Beginning about a month before the breeding season, the ram should be given some extra grain. Two parts of oats and one of bran by bulk form an excellent mixture. Oats alone are also very good. If the ram is thin the following mixture is excellent: Corn, 5 parts; oats, 10; bran, 3; and linseed meal, 2 parts, by weight.

The number of ewes a ram will serve depends largely upon his age and the way he is handled. A ram lamb may serve from 5 to 15 ewes, depending upon his maturity. A yearling may serve from 15 to 25, while a mature ram well cared for should serve from 40 to 60 if allowed to run loose with the flock. By permitting him to be with the ewes an hour morning and evening more ewes can be bred. If the ram is old or injured or is to be bred very heavily, another ram may be used to locate the ewes in heat and thus save the older ram from the necessary work of circulating through the flock. A bag or a piece of cloth tied under the belly prevents the “teaser” from serving the ewes. If the ram is allowed to run in the field with the ewes he may be made to mark the ones he has served, so that the approximate dates of lambing can be determined. A daub of special branding paint that later will scour out of the wool can be applied every day or two to the left side of his chest and brisket for the first two weeks, on the right side of the next two, and on the middle for the last two weeks of the season. Different colors of paint may also be used, but under no consideration should any mixture containing tar be used. When the ram is not in the flock he will be quieter and more easily handled if one or two ram or wether lambs or bred ewes are kept running with him.

FALL FEEDING

Stubble and stalk fields may well form the principal means of sustenance for the breeding flock in the fall if they are used before the rains injure their feeding value. Fence strips in plowed fields may also give good grazing for a few days. Clover and grass pastures may well be left until the stubble and stalk fields have been used. For regions where the winters are open a heavy stand of well-cured bluegrass will help very much in carrying the flock through the winter in good condition. Green rye pastures in the late fall give considerable succulence and furnish exercise for the flock. In the South velvet beans will be found of great help in carrying the flock into January.

The shepherd should train himself to read the condition of his sheep by feeling the bone of the loin or back. At no time while they are in lamb should ewes be allowed to lose in weight. In open wet fall seasons there is danger of waiting too long to start feeding. A rank growth of soft grass may appear to be good feed, but the real need of the flock should be determined by a closer examination of the actual condition of all or a representative number of the ewes.

THE FLOCK IN WINTER

WINTER FEED

Winter management has a very important relation to the returns from the flock. The feeding should be such as will produce the most vigorous lambs and at the same time keep the wool in good condition. Leguminous hays, straws, and cornstalks usually form the main part of economical winter rations. Clover, alfalfa, or cowpea hay, if of good quality, may be used as the sole feed until near lambing time, from 3 to 3 ½ pounds being sufficient for ewes weighing less than 150 pounds. Oat and wheat straw are better than rye or barley straw. The beards of the latter are likely to prove troublesome. Cornstalks placed where the ewes can eat off the leaves may be used as a part of the roughage ration. If this ration is made up largely of cornstalks or straw, a nitrogenous concentrate should also be used. Timothy hay is not good sheep feed.

Such succulent feeds as roots or silage are desirable in keeping the ewes in good health. The use of silage will often materially reduce the cost of the ration, but silage can not safely be used without any hay. Only silage from well-matured corn should be used for sheep, and caution should be exercised to guard against feeding spoiled, frozen, or moldy silage. It is not advisable to feed more than 3 pounds per head daily of this feed.

For bred ewes, roots, particularly turnips, should be used sparingly until after lambing. Each of the following rations contains approximately the amount of the various nutrients required daily for ewes of from 120 to 145 pounds in weight when in dry lot:

(1) 3 pounds alfalfa or cowpea hay, 2 pounds corn silage, ½ pound shelled corn.

(2) 3 pounds alfalfa, 2 pounds corn stover (amount eaten).

(3) 3 ½ pounds alfalfa hay, 2 pounds corn silage.

(4) 2 pounds oat straw, 2 pounds corn silage, ¼ pound linseed meal, ¾ pound corn.

Where the ewes can run on fall wheat or rye during the winter months the pasture should be supplemented by some dry or concentrated feed. Silage or roots are not desirable when the pasturage is soft or green. One-half pound of cottonseed meal contains the daily requirement of protein for pregnant ewes. When price suggests the use of this concentrate, the other feeds should be of a carbonaceous character. One-quarter pound of cottonseed meal per day and a selection of other feeds will be better than a ration containing a larger amount of cottonseed meal.

EXERCISE IN WINTER

If the lambs are to be born strong and vigorous, a moderate amount of exercise is necessary for the ewes during the winter. This can be obtained by scattering their roughage over a field and allowing them to work back and forth over it while eating, or by feeding some of the roughage some distance away from their shelter. If winter pastures are used, no other arrangement for exercise is necessary. At no time should the pregnant ewes be forced to wade through deep mud or snow, neither should they be chased by dogs nor forced to jump over boards nor to pass through narrow doors, as such treatment is sure to cause loss of lambs or of both ewes and lambs.

If fleeces are allowed to become soaked with rain or wet snow, colds and pneumonia may result. Dry snow, on the other hand, has no ill effect, as the ewes readily shake it off.

THE LAMBING SEASON

IMPORTANCE OF CARE DURING LAMBING

The lambing season is the shepherd’s harvest time, and the size and quality of the crop practically determine the profits. A large crop of good lambs is the base of good financial returns, while a small crop of lambs means less profit, and if they are inferior in quality great skill and care are necessary to make any profit. At this time extra attention must be given to the ewes and lambs. In no other way can time be used to better advantage on the farm. If a record of the date of service has been kept, the approximate date of lambing can readily be foretold, for the ewes will generally carry their young about 145 days (5 days less than 5 months).

CARE OF THE EWES

Heavy grain feeding just before lambing is likely to cause udder troubles. At this time the wool around the udder should be clipped short to allow the lamb to find the teats readily. Just before lambing the ewe becomes restless and appears sunken in front of the hips. She should be put in a separate pen, which may be made of two light panels fastened together by a hinge and set in a corner.

These panels permit the ewe to see the other members of the flock and prevent her from becoming excited or nervous. Their use also prevents other sheep from trampling on the lamb, and the ewe has a good chance to get acquainted with her lamb at the start, thus avoiding the danger of disowned lambs later. These lambing pens should be in a well-ventilated room that is free from drafts and as warm as it can be made without artificial heat. In very cold weather a blanket thrown over the lambing pen will insure sufficient warmth to give the lamb a good chance in the first few hours, which are important ones.

TROUBLES AT PARTURITION

Well-fed ewes seldom have much trouble in lambing, but there may always be need of assistance for a few ewes. If the ewe strains for half an hour without delivering the lamb, aid may then be given. The normal position of the lamb at birth is to have the forelegs extended with the head lying between then. If the lamb is not in the proper position, the shepherd should correct it by inserting the hand and arm into the vulva and effecting the change. When such assistance is needed the shepherd should first trim his finger nails and rub Vaseline or oil upon his hand. In either case, when the position is correct the lamb can usually be successfully delivered by looping a string around the front feet and pulling outward and downwards as the ewe strains. If the womb and vagina have been lacerated by the operation, it is well to use a solution composed of one-half ounce of zinc sulphate and 2 ounces of tincture of opium in a quart of water at blood heat. This should be poured into the womb by means of a rubber tube and funnel. If the ewe seems weak a stimulant should be given.

WEAK LAMBS

The lamb that is born strong and vigorous, with a good dam, will need little care. If the shepherd is present at the birth of a weak lamb, he should wipe away the phlegm or membrane from the nostrils of the lamb, and, if not already broken, the naval cord should be severed. Blowing into the mouth and nostrils and slapping gently on the ribs, first on one side and then on the other, will often save the life of a lamb that is apparently dead.

In cold weather lambs may get chilled and die unless prompt remedies are used. Wrapping the lamb in hot flannel cloths, which are renewed as often as necessary, is an excellent method of warming it. Another method is to place it for a few minutes in water as hot as the hand can bear; then remove, dry with cloths, and wrap up for an hour or two in fresh cloths or a sheepskin to complete the drying process. In any case milk should be given freely and the lamb returned to the ewe and allowed to suck as quickly as possible. If it does not suck when held to the teat, an infant’s nursing bottle and nipple may be used. A few teaspoonfuls each hour for a few hours will usually give strength to enable the lamb to nurse without assistance.

DISOWNED LAMBS

Little trouble is experienced with disowned lambs where lambing pens are used. With a ewe that refuses to own her lamb it is sometimes sufficient to draw some of the milk and rub it upon her nose and also upon the rump of the lamb. A heavy-milking ewe with only one lamb can sometimes be made to adopt an orphan or the disowned lamb of a lighter milking ewe. When there is difficulty in having a ewe adopt another lamb after losing her own, the skin of the dead lamb may be fastened over the lamb to be adopted. This skin should be removed in two or three days, after which no trouble is usually experienced.

ORPHAN LAMBS

If for any reason a lamb is permanently orphaned it may be raised by bottle feeding, whole cows’ milk or goats’ milk being commonly used. Very young lambs should be fed milk from ewes which have also recently lambed, when it is possible to obtain it. For the first two days they should be fed 1 ounce every two hours, after which they can be changed to cows’ or goats’ milk without difficulty. Milk should always be fed from sterilized bottles and at about body temperature, or 100 degrees F. Care should be taken to feed frequently and in small quantities. Best results are obtained by feeding every four hours for two or three weeks at a rate per feeding gradually increased from 2 to 6 ounces. At this age they should be nibbling some hay and grain (bran, rolled oats, or cracked corn), and the period between feedings can be gradually increased to eight hours, while the amount fed should be increased to 1 pint.

YOUNG-LAMB TROUBLES

Well-nourished lambs from well-fed ewes have few troubles, but some troublesome conditions are to be expected in any flock. The causes and remedies of the more common ones are given below.

Constipation is indicated by straining and distress and may be remedied by a teaspoonful of castor oil. White scours can best be cured by giving one-fourth of an ounce of cooking soda, 1 ounce of sulphate of magnesia, and a pinch of ginger in a small quantity of flaxseed tea or gruel. This should be followed in about four hours with 2 ounces of linseed oil. Indigestion is shown by distress and frothing at the mouth. A liberal dose of castor oil will effect a cure in most cases.

Sore eyes are of rather common occurrence. The eyes appear covered with a milky scum, or, in bad cases, become an angry red. In either case tears are apt to flow profusely. An eyewash of silver nitrate or 15 per cent argyrol will clear them up in a few applications. A very tiny drop of pure sheep dip is also recommended. Sore mouths are sometimes caused by scabs around the lips. These scabs should be rubbed off and sheep dip or a medium-strength solution of copper sulphate applied.

DOCKING THE LAMBS

Docking, or removing the tail, is best done at the age of 7 to 14 days.

CASTRATION

The ram lambs may well be castrated at the time they are docked. Both operations should be done early on a bright, cool morning.

(Editor’s note: The preferred modern procedure for the above two operations involves the use of specially designed rubber bands and a banding plier.)

TREATMENT OF EWES AFTER LAMBING

The shepherd should watch the ewe’s udder closely to see that it is in good condition, for good lambs can not be raised from ewes not milking freely. Ewes that have lambed should be kept in lambing pens from one to three days and then turned in a pen by themselves, where they can be given special feed and care. After lambing they should be fed lightly at first, being put on full feed about the third or fourth day. At this time it is economy to feed heavily enough to produce a large flow of milk for the lambs. Heavy-milking ewes can make good use of from 1 to 2 pounds of grain per day. Experiments conducted at the Wisconsin Experiment Station showed that when ewes were on good pasture there was no extra gain made by the lambs when the ewes were fed grain.

THE FLOCK IN SUMMER

SHEARING

Shearing is generally done in late spring or early summer, after lambing. It should be done on a warm day, so that the ewes may not become chilled. Formerly shearing was done mostly by the use of hand shears, but in most flocks of large size power shearing machines are now used. For small flocks under 50 head hand-power machines are the most economical. The machines are more rapid, smoother work is done, and the ewes are injured less. It is easier to learn to use them, and more wool is obtained than where hand shears are used.

The tags or dung locks should be removed from the fleece, and then it should be rolled up, not too tightly, skin side out, and tied with paper twine. Wool buyers prefer this method of tying to that done with wool boxes.

If the lambing is late the ewes may be sheared before lambing, but great care must be used in handling them. It is better to do the shearing after lambing. In either case it should be done before hot weather sets in.

DIPPING

Sheep are dipped to free them from ticks, lice, and other skin parasites. A convenient time for dipping is shortly after shearing in the spring. Less dip per animal is needed and the weather is usually more favorable at this time than at any other season. The dipping should be done in the morning of a clear, quiet, warm day, so that the sheep will be dry by night and will not catch cold. Every member of the flock should be dipped, and it is well to spray the inside of the sheep barn with dip at this time. Any standard dip solution can be successfully used, if the manufacturer’s directions are followed. To insure the eradication of sheep ticks the sheep should be dipped a second time about 24 days after the first dipping. About 10 days should be allowed to elapse after shearing, so that shear cuts may have time to heal before dipping.

CULLING THE EWE FLOCK

The summer or early fall, soon after the lambs have been weaned or marketed, is the best time to dispose of ewes that are not considered desirable for another year’s breeding. The ewes that are to raise the next crop of lambs can then be prepared for fall breeding. Ewes of the mutton breeds do not ordinarily breed well nor keep in good condition after 5 years of age. Their usefulness, however, depends more upon the condition of their teeth than upon their actual age. Fine-wool ewes usually remain useful to a later age. It is a good plan to sell aged ewes before they become too run down to be valuable to the butcher. The ewes that give the most milk and raise the best lambs are likely to be quite thin at this time and should not be judged by their appearance.

Non-breeding ewes, poor milkers, light shearers, and mothers of inferior lambs should be marked as their defects are discovered and should be disposed of at this time. Their places should be filled by the best individuals among the yearling ewes and from the best breeding older ewes.

WEANING THE LAMBS

If lambs are sold at from 3 to 5 months of age, they may run with their dams until that time. Lambs to be kept for breeding purposes should be weaned at from 4 to 5 months old and put on fresh pastures, where there is less danger of stomach worms. When the weaning is done at this time the ewes can be put in better condition for the fall breeding. Ram lambs left in the flock worry the ewes and may get some of them in lamb. When lambs are to be kept on the farm the best method of weaning is to leave them on the old pasture for three or four days and remove the ewes to a scanty pasture to check their milk flow. As soon as the lambs cease fretting for their dams they may be moved to fresh pastures where the ewes have not been. Ewes with large udders should be partially milked once every three days until they go dry.

SUMMER PASTURES

The breeding flock in summer needs little except good pasture, shade, salt, and plenty of fresh water. Bluegrass is one of the most popular pastures, but is likely to be too dry in late summer and too unbalanced in its food nutrients for ideal feed. It is at its best when used in the spring and fall and supplemented by forage crops in the summer. Alfalfa is sometimes pastured in the summer, but is better used when cut and fed as hay in the winter. There is some danger of loss from bloating when sheep are grazed on alfalfa or clover. Sweet clover is worse than the red and alsike in this regard. Sheep should be given a good feed before being turned on such pastures, and the alfalfa and clover should be dry. When these precautions are taken little difficulty should be experienced from bloating. Rape makes an excellent supplement for bluegrass, but is a forage crop rather than a summer pasture, though it may well supplement bluegrass. Soybeans are good, and if the flock is changed to another part of the field when most of the leaves have been eaten off, the plants will make further growth for later use. Cowpeas are good for the older sheep, though unpalatable to lambs. Bermuda grass, when kept short, is especially good when reinforced by lespedeza and bur clover, which grow at different seasons from the Bermuda grass and here find their best use as a sheep pasture. The aftermath of grain and timothy fields furnishes feed for many flocks and helps greatly to bring down the cost of carrying the flock through the summer.

AVOIDING STOMACH WORMS

In many farming sections the flockmaster’s most serious troubles are likely to be caused by internal parasites, the effects of which are particularly evident during the latter part of the pasture season. Of these parasites the stomach worm is the most common and troublesome. It occurs wherever climatic conditions and methods of keeping the flock are favorable for its development, which means on most farms, and probably all. No practicable means entirely avoiding infection with this parasite has been discovered, but by proper arrangement of the summer pasturage and some medicinal treatment in the region of the Corn Belt and the South it is possible to keep the numbers of the worms below the danger point. A knowledge of the development of this parasite affords a basis for the changing of pastures and medicinal treatment that insure a healthy condition of the flock.

The stomach worms live in the fourth stomach. They are from one-half to 1 ¼ inches long and have a fine red stripe running in spirals from end to end of the body. Their eggs pass out in the droppings of the sheep and hatch in a few hours, days, or weeks, according as the temperature is high or low. At temperatures lower than about 40 degrees F. development is arrested. The larva which hatches from the egg molts twice and then crawls up on the grass blades when they are moist, and as it remains coiled on the blade it may be swallowed by some animal. Eggs or young, uninfective larvae may be killed by freezing or drying, but the infective larvae on grass will sometimes live. After being taken into the body of a ruminating animal they develop into the mature worms. Cattle and goats usually are not so seriously affected as sheep, but sometimes are seriously injured or killed.

The injurious action of stomach worms has been attributed to various things: the loss of blood extracted by the parasites; the loss of nutritive materials which may be absorbed by them; interference with digestion; and the destruction of red corpuscles by a poisonous substance secreted by the parasites which is absorbed into the blood. Lambs that are affected become anemic, thin, and weak and may either die or continue for a long time in poor condition and fail to grow as they should. Visible indications of the anemia (thinning of the blood) caused by the parasites are the white, paperlike appearance of the skin and the mucous membranes of the mouth and eyes and the watery swellings which develop under the jaws. The condition is sometimes referred to as “bottle jaw” or “poverty jaw.”

Treatment of infected lambs will bring about recovery if given in time, although, as before indicated, the safest and cheapest way of combating the trouble is by preventing it. Young lambs are very unlikely to become seriously infected by larvae developed from eggs dropped by older sheep in barns or yards bare of grass. On a noninfected pasture the larvae will not ordinarily develop in any considerable numbers to the stage at which they can infect sheep in less than 10 days or 2 weeks. If the flock is moved to fresh, noninfected ground by that time, the danger is avoided for a further period of the same length.

It is not known how long larvae of this parasite will continue to be dangerous, but, since freezing commonly kills unhatched eggs, a pasture in cold climates that was not used in summer and fall until after frost will be practically safe for occupancy by lambs for a limited time the following spring or summer, provided the old sheep are removed from it before the winter is over. This fact, and the desirability of obtaining the maximum amount of grazing from small areas, thereby reducing the amount of fencing needed, makes it advisable to adopt the plan of having a rotation of forage crops for summer use. Land on which fall wheat or rye has been sown will be safe for spring use, and if plowed and sown to rape or other crops for later grazing is then also free from serious stomach-worm infection.

On farms where sheep have not been previously kept trouble from stomach worms is not likely to be serious until the second or third summer.

PREPARING LAMBS FOR MARKET

ADVANTAGES OF EARLY MARKETING

Under ordinary farm conditions in the latitude of the Corn Belt and in the south lambs should be made ready for market at from 3 to 5 months of age. When young they make a higher rate of gain and will put on the same amount of flesh for less cost than when they are older. Then, too, they will make but small gains during the heat of summer, and at this time parasites are most troublesome and they are thus more liable to losses from this cause. Risk of accidents is always higher when the lambs are held for a long time. More feed is saved for the breeding flock and less labor is needed if the lambs are sold early. Better prices are obtained in the spring because of not having to meet the competition of the western lambs that are marketed during the summer and fall, and in addition the grower gets the use of his money sooner by pushing the lambs to a marketable condition as fast as possible.

In New England and similar territory where grain and choice legume hay are expensive, but where summers are comparatively cool and good pastures prevail, it has been found more profitable to have the lambs born during pasture time in May and June. By this plan the pastures furnish all the feed that is required for the flock from the time the lambs are born until they go to market in early November.

Considering farm lamb production for the entire country, it is advisable to have the lambs ready for market either before or after the rush of lambs from the western range States. Therefore in the latitude of the Corn Belt and in the South, where the summers are too hot for late lambs, the lambing period should be early enough to have the lambs finished and ready for the market by May or June or at least not later than early July. In New England and similar territory of that latitude, where grain and other winter feed is relatively scarce and expensive and where summers are comparatively cool and pastures good, it is more profitable to have the lambs ready for market in early November, just after the rush of western lambs.

POSSIBILITIES OF LATE MARKETING IN NEW ENGLAND

Under ordinary farm conditions in New England and similar territory where good pastures are abundant and summers are relatively cool, late lambing can be made a profitable practice. The experience of the United States Bureau of Animal Industry in New England has shown that lambs born on pasture in May and June and marketed early in November are considerably more profitable than lambs born in February and March and marketed early in July. The chief reason for this is the difference in cost of feed.

The flocks producing the late lambs on good pasture require no grain throughout the year, whereas the ewes producing early lambs need grain from about one month before lambing until pasture is abundant, and the early lambs must have grain from the time that they will eat it (at 1 or 2 weeks old) until they go to market. Another advantage of late lambing in New England is the fact that the late-lambing ewes require much less attention during the lambing season than the ewes that bring their lambs in February or March.

In the New England lamb-raising experiments the bureau has found it necessary to protect both early and late lambs against stomach-worm infestation by medicinal treatment. Frequent change of pasture is also not only an aid to stomach-worm control, but helps to keep the flock in thrifty condition.

TEACHING THE EARLY LAMBS TO EAT

Every effort should be made to keep the lambs growing from the start. The first essential is to teach them to eat. Liberal feeding of lambs dropped before pastures are ready is profitable under any ordinary grain prices. This is best done through the use of a small enclosure known as a “creep,” to which the lambs have access at all times, but into which the ewes can not come. The creep should contain a rack for hay and a trough for grain, so arranged that the lambs can not get their feet into them.

All feed given, especially ground feed, should be clean, fresh, and free from mold. The lambs will begin to nibble at the feed when from 10 to 16 days of age. Pea-green alfalfa of the second or third cutting is one of the most relished feeds. Flaky, sweet wheat bran probably ranks next. For the first few days these are the ideal feeds. A little brown sugar on the bran at first will make it more palatable. Linseed meal is also good when mixed with the bran. Until the lambs are 5 to 6 weeks old all their feed should be coarse ground or crushed. The Ohio Experiment Station has found that for young lambs that are to be marketed a grain ration of corn is of about the same value as one of corn 5 parts, oats 2 parts, bran 2 parts, and linseed meal 1 part. Linseed meal is especially relished by lambs at this time and would be especially valuable in promoting growth rather than fat.

Such feeds as middlings are too floury for extensive use. Rye is less palatable than oats or barley. Soybeans may replace the linseed meal if they cost less. Cleanliness is an important factor in keeping the lambs growing. Always feed to an empty trough, and if it becomes soiled scrub it out with limewater.

RAISING CORN BELT AND SOUTHERN LAMBS ON PASTURE ALONE

The plan of having lambs dropped after ewes go to pasture and marketing them without the use of other feed for the flock seems to have a place in New England and similar territory of that latitude, but it can be recommended for general use only in the latitude of the Corn Belt or the South when pasture is abundant. The main advantages of this plan lie in the small amount of care needed and the lower feed cost. The cost, however, depends upon the quality of the pasture and the value of the land. Late lambs that have never received grain are particularly liable to be injured by stomach worms in case of short pasture or heavy pasturing of the land with sheep. Lambs make smaller gains in hot weather, and there is the possibility of droughts drying up the pasture and decreasing the ewes’ milk at the time of the lambs’ greatest need. Feeding grain to lambs on pasture is only partially satisfactory and is particularly unlikely to be profitable with lambs that have not learned to eat it before going to pasture.

When grass pastures are to be used for a flock turned out when the lambs are 5 to 8 weeks old, it is desirable to have sufficient division to allow frequent changes without the lambs being returned to any ground previously grazed in the same season.

THE DRY-LOT METHOD

Some breeders of purebred sheep have practiced a dry-lot method of raising lambs, mainly to avoid stomach-worm troubles. Under this plan the lambs do not leave the sheds or yards until they are weaned, when they are put on clean, fresh pastures. In the meantime they are fed hay and grain, and their dams are returned from the pastures two or three times each day to allow the lambs to nurse. Because they do not graze, the lambs have slight chance of becoming seriously infested with stomach worms.

Some raisers of market lambs follow the plan of keeping both ewes and lambs in dry lots. This plan also prevents serious stomach-worm infestation. Where green feeds or soiling crops are grown near by and fed in the lot, the ewes milk well and the lambs grow at a profitable rate. The main advantage from such a soiling system is that it insures freedom from injury by internal parasites. Less fencing is needed if the ewes can be grazed elsewhere after the lambs are sold. If this can not be done, as much fencing will be needed for the ewes in the fall as would have been required for the spring flock.

This plan is most likely to work well where alfalfa is the main crop. Feeding in the yards prevents loss from bloat, and there is no need for plowing the land, as would be necessary if sheep were to graze on it a number of times each season.

THE FORAGE-CROP METHOD

The practice of grazing the flock on forage crops until the lambs are sold is becoming popular where lands are high in price and where stomach worms cause trouble. Under this plan the ewes and lambs are first grazed on fall-sown wheat or rye. The land is divided to avoid the necessity of keeping the flock longer than 10 to 14 days upon the same ground. By the time the second lot of this crop is grazed down, spring-sown peas and oats can be ready and the fall-wheat ground plowed and reseeded to another cereal or to rape or soybeans for later use. Such a plan requires some labor in preparing and seeding the land, but it produces the largest amount of feed per acre and prevents trouble from the stomach worms.

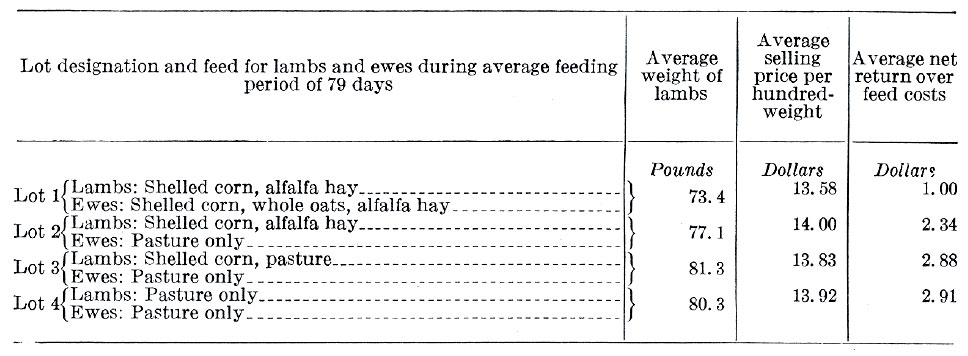

Experiments conducted at Purdue University Agricultural Experiment Station, Lafayette, Indiana, in which comparable lambs were produced by four methods of feeding, over a period of three years, showed that good, fresh pasture, when available, at all times gave the greatest return over feed costs. Table 1 presents the comparative data.

When the pasture was only fair, however, some grain fed to the lambs in creeps appeared beneficial. This method produced the heaviest lambs (lot 3), but they had less finish than those in lot 2, fed on alfalfa hay and grain. Using harvested feeds exclusively for both ewes and lambs (lot 1) is too expensive for producing lambs to be placed on the regular market at a time when they must compete with grass-fed lambs. If soiling crops could be used instead of hay under this dry-lot method, there would no doubt be some reduction in feed costs, but this method seems more adapted to the production of high-quality purebred lambs or lambs for a specialized market.

In the experiment described the ewes were uniform in type, age, and thrift and were managed under uniform methods during the winter. They were divided into four equal lots as soon as the lambs were ready to go on pasture for an average feeding period of 79 days. The methods of feeding cited were used only during the period in which the lambs were being raised and were independent of the feeding before lambing time.