Great Grandfather Cooper’s Hop Farm

Great Grandfather Cooper’s Hop Farm

text and illustrations by Tim Hamwey of Worcester, NY

The shadows grew longer across the fields as the hop pickers loaded their day’s work onto the wagon. The searing heat of the day had subsided, and the sultry August haze had softened the focus of the setting sun. A chorus of insects had begun calling from the hedgerows and the songs of the vesper sparrows added their enchantment to the tranquility. The stacks of harvested hop poles broke the gradual curves of the hop yard and punctuated the horizon. The voices of the jovial pickers blended into the late summer sounds from the fields as preparations were made for the trip to the hop kiln. The landscape surrounding the hop harvest of the late nineteenth century had a rich fundamental beauty. Even though a large number of people and teams of horses worked the land, the sounds, smells and beauty of nature still dominated these harvest scenes and made the farms a harmonious part of the landscape.

My great grandfather, William Cooper, owned the family farm just south of Cooperstown during the time when hop production was at its peak in Otsego County. The family was related to the Coopers that settled Cooperstown and of the thirteen siblings raised on the homestead, he took over the farm. He was nearly self-sufficient and marketed a variety of products from his farm, but the profit from his hop yards was so significant that he was known as a hop farmer. His diaries are filled with entries related to his yearly care of the hops.

August 30, 1875 – “Father commenced picking his hops today with eight pickers. I am to tend box for him. Libbie and Emma McLean and Charlie Smith and Zera Newton pick to my box.”

In Otsego County, the hop grower’s year culminated in the luxuriant days of late August when the hop blossoms were mature and ready for picking. The whole community was involved in the labor-intensive job of picking, drying and pressing the hops. “Hop time” was looked forward to as a time for socializing, meeting new people and taking a break from the usual farming tasks as well as a time for everyone, even women and children, to profit financially from the hops. But the hop fields needed very special care that was quite different from the care needed for any other crop raised on these farms and my great grandfather worked nearly year-round to maintain successful hop production.

September 9, 1877 – “We finished picking our hops today. We had 152 boxes. Arthur and I earned $13.00 tending hop box for Mr. Uppham. Flora earned $5.20 picking hops there. Flora picked three boxes of hops.”

The hops were an unusual crop for these farmers to culture. The vines were the only perennial row crop. The roots, once established, would live for many years but, to yield plentifully, they had to be well cared for. Hop vines still grow on abandoned hop farms around Otsego County from the same roots planted in the nineteenth century. Also, hops were the only major crop raised on the farms in this area that the people had practically no use for themselves. All other crops were an expansion of the products the farmers would have raised for themselves. No one made beer and this odd plant was an import to the area. The diseases and pests and cultural requirements were unique to this plant. The growing habit necessitated support on tall poles that needed continual attention and replacement. The hop vine can grow up to 40 feet in a summer and this bulk of annual growth requires extremely heavy fertilization.

May 30, 1876 – “I churned in the morning. Drawed ashes and plaster out to the hop yard.”

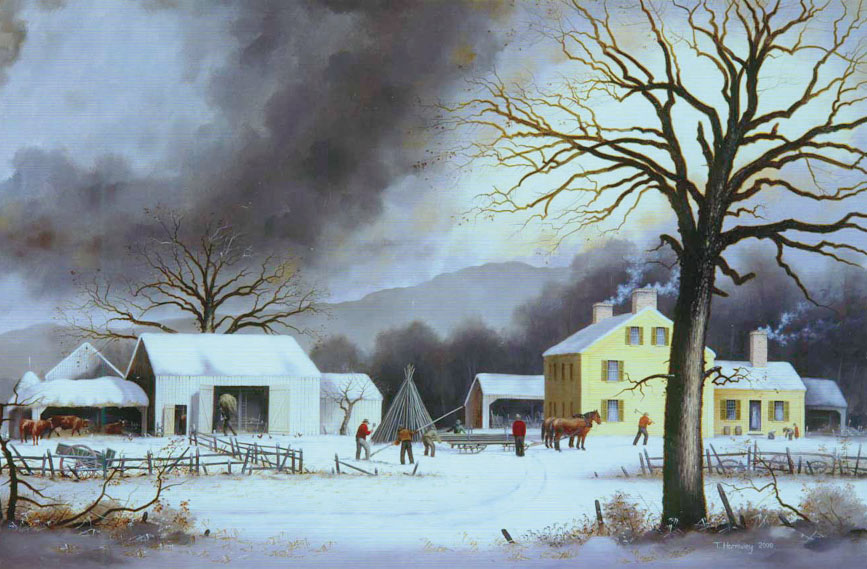

During the winter months, sometimes even before the previous year’s hops were sold, my great grandfather worked on cutting hop poles from his woodlots and preparing them for the coming season. Young trees were selected from the hardwood stands where they grew tall and slender up to the canopy. He would cut trees that were around five inches in diameter at the base and 20 to 25 feet tall. He usually used Chestnut trees for hop poles in his own yards. Before the Chestnut blight was imported with European and Asian Chestnut trees around 1906, the Chestnut trees made up around 25% of the forests in this area. Chestnuts were especially resistant to decay when set in the ground and because such a large number of poles were needed by the hop farmer, it was important to have them last as long as possible.

My great grandfather’s woodlots supplied him with a tremendous number of trees for hop poles. He also sold a large number to hop farmers around Cooperstown, creating another cash crop for the family.

February 10, 1877 – “Judge Harris bought 3000 hop poles of me today through his agent Mr. Berry of the hop factory. $2.50/100 poles.”

February 27, 1877 – “Harris paid me $139.50 for hop poles today.”

May 8, 1875 – “In the afternoon I rossed (debarked) hop poles for the Second National Bank of Cooperstown. I rossed 112 poles and stacked them.”

William also kept a large supply of seasoned hop poles ready for replacements during the growing season. Some poles became weak due to slow decay over several seasons of use and storms broke many.

June 8, 1874 – “The shower tore things to pieces last night very badly and the hail cut the hops to pieces very badly. There was three or four hundred hop poles broken.

Saplings were cut, rossed, sharpened on one end so they could be forced into the soil more easily, and stacked against one another in pyramid style to season.

January 13, 1874 – “William and I worked for Hiram Cornish today cutting hop poles. We cut over 500 and piled them.”

March 5, 1872 – “I sharpened hop poles a little while today.”

Removing the bark from limb-wood like these poles slows down decay because not only does the wood season more rapidly without bark, but the bark soaks up and holds moisture longer and contains phloem and stored nutrients that promotes decay. The bark also seals moisture in so even removing strips on three sides was quite effective.

November 27, 1875 – “Cut 600 hop poles.”

March 21, 1874 – “I helped Adrial draw out hop poles in the forenoon. In the afternoon I went up and sharpened hop poles. I sharpened 144.”

May 1, 1874 – “I rossed and sharpened hop poles all day. Earned $3.00 today. A very good day’s work.”

February 18, 1877 – “Ted drawed hop poles (3100 hop poles).”

May 14, 1875 – “I worked at the hop poles today. I rossed 400. I am very tired tonight.”

May 17, 1875 – “I set up one of the stacks of hop poles today that had blown down.”

To put on the heavy growth necessary to produce a profitable crop of flowers, the hop ground had to be well prepared early in the spring before the roots of a new hop yard were set out. My great grandfather’s farm was a hill farm with thin, rocky, heavy soils. He had to prepare the soil in his yards to be deep, light and fertile. In preparation, he cut off the timber the year ahead and usually burned the brush before he plowed.

July 26, 1877 – “It is very warm today. Arthur and I burned the fallow. There was a big fire.”

The soil had to be plowed as deep as possible, and before much more could be done, a tremendous quantity of rocks had to be picked and removed to the hedgerows. Picking rocks was considered a yearly, routine part of farming in this area at the time. Frost and the working of the field would turn up a perpetual supply of rocks from the subsoil. The subsoil in some areas was given the name of hardpan because it was mostly rocks embedded in hardened clay from which farmers tried to create arable soil.

After the ground was prepared, my great grandfather marked out the hop yard. He would mark rows about 6 feet apart going both the length and width of the hop yard. At the intersection of these rows, he would plant root cuttings that he purchased from neighbors. An established hop plant sends out side shoots to spread the plant. In cultivating an established yard, these rhizomes would be cut back by the horse hoe. In this way, the cuttings would not be missed and the number of vines that would grow from each hill would be kept to minimum, resulting in better production.

May 28, 1873 – “Hiram and I marked out hop yard and planted potatoes.”

October 22, 1873 – “I went up to Hiram’s to work today. We dug hop roots and set in the missed hills in the forenoon. We manured hops in the afternoon.”

May 3, 1877 – “I got my hop roots today. ½ bushels of Father Newton, 7 bushels of Judson Cornish, cost $8.50.”

May 4 1877 – “I cut hop roots and marked out hop ground.”

May 5, 1877 – “I marked out hop ground in the forenoon. Arthur hurt the Uppham colt very badly today. Stuck a stick in her breast.”

May 10, 1877 – “I sharpened hop poles today and Arthur drawed them out onto the hop yard.”

After the roots were planted, the poles would be set and the yard would be cultivated continually throughout the growing season. The first year the hops were seldom very productive, but a mature yard would be so dense that cultivation would cease as the vines filled in the rows.

May 4, 1876 – “I dug hop roots in Father’s hop yard.”

May 9, 1876 – “Commenced setting hop poles.”

May 18, 1876 – “In the forenoon Clarence and I set in missed hop hills in the hop yard. There are nearly one third out.”

May 23, 1876 – “Clarence set out hop roots.”

Healthy hop vines put out a remarkable growth. As the shoots emerge in the spring they begin nutation which is a movement in a spiral motion in the air around a central axis until they touch and twine around some solid object. The hop farmer intends this object to be his hop pole. Nutation in the northern hemisphere spirals counterclockwise looking up from the earth so the farmer must train the vines around the pole in the proper direction and then tie them gently to the pole. My great grandfather wore a burlap bag around his waist as an apron and he would unravel a cut edge to get soft ties for the hops as he walked from hill to hill. My grandmother, Edna Cooper, described to me vividly how she tied hops as a girl in the first decade of the 1900s on her father’s farm.

May 28, 1877 – “Arthur trimmed hops and tied.”

June 4, 1872 – “Hoed roots.”

April 22, 1873 – “I and Arthur set hop poles in the forenoon. In the afternoon we drew wood and hay and skinned a calf.”

May 24, 1873 – “We finished setting hop poles today.”

May 25, 1873 – “It is a warm and beautiful day and nature is putting on her beautiful dress of green.”

In an established hop yard, my great grandfather began the year by grubbing out the hills. The hop grubber was a type of hoe with four tines instead of a blade. It was used to clear away the old dead growth from the previous year and pull back some of the soil that had been hilled up around the plants during last summer’s cultivations. This had to be done early enough so that the tender shoots would not be developed enough to be damaged. Then the poles had to be set. The poles were sharpened, but a hole about 2 feet in depth was made with a heavy iron hop bar. The end of the hop bar is pointed to penetrate the soil but the diameter increases steeply for about 10 inches to give the user more leverage to pry open a hole large enough for the hop pole to enter. With each stab of this hop bar, the hole is deepened and pried open to size.

May 11, 1875 – “We planted the hops, three acres in the forenoon. In the afternoon we planted potatoes.”

The hop plant does not compete well with weeds. Also, because the yard is perennial, any established grasses or weeds would have a chance to take over the yard. My great grandfather’s diaries have many entries about cultivating the hops throughout the season. He would use a single horse that would quickly learn the routine of how to pass down the hop yard. The camaraderie established between the farmer and his work horses is difficult to explain to a person who has never worked this way, but a good horse quickly learns what is required of him and eagerly tries to please and look out for his leader. Great grandfather Cooper used a plow to hill up the soil around the plants and a horse hoe to loosen and kill the weeds between the rows.

July 2, 1875 – “I sent for a horse hoe. It will cost $6.00.”

May 27, 1873 – “I finished ploughing the hops today and then hoed hops the rest of the day.”

June 4, 1874 – “I hoed hops all day.”

May 21, 1875 – “I ploughed out hops for father in the forenoon. In the afternoon I went up to Springfield after my wagon. Went afoot and horseback. I staid at Mr. McLane’s all night. They seemed very glad to see me. There was a very heavy thunder shower tonight.”

The hop yards were fertilized very heavily throughout the year until the dense growth prevented the horses from passing through. My great grandfather had quite productive hop yards and only vines grown in fertile soils produce well. William wrote often about manuring the hops and plastering (liming) the hops. The plastering freed up important minerals for the crops that were bound in acid soils.

November, 10, 1877 – “Irve manured hops.”

May 31, 1876 – “Clarence and Edie tied hops in the forenoon and I plastered hops. Clarence then cultivated hops and I plastered them.”

June 1, 1876 – “Clarence ploughed buckwheat ground and I cultivated hops.”

May 11, 1877 – “Arthur and I ploughed out the hops today.”

May 12, 1877 – “Arthur and I grubbed hops in the forenoon. Worked on the new privy.”

May 14, 1877 – “Arthur hoed hops in the forenoon. I helped him awhile and marked out some corn ground.”

June 9, 1877 – “I cultivated hops and potatoes and Arthur tied hops in the afternoon. He cultivated and I made fence. I sold my wool to D. T. Pratt to day for 33 cts per pound.”

June 20, 1877 – “Arthur and I finished hoeing and trimming the hops and plastered them and the potatoes.”

June 25, 1877 – “I ploughed hops and potatoes all day or until supper time. Then Flora and I went to the hop factory and then to Cooperstown. Arthur hoed hops all day.”

June 26, 1877 – “Arthur and I finished hoeing the hops in the morning and then I went to ploughing potatoes and he to hoeing them.”

Hop vines are dioecious, having male and female flowers on separate plants. The male staminate plants were necessary for pollination, but only the pistillage flowers would ripen into the papery fruits that the hop farmer picked and processed. Therefore, the hop farmer would intersperse a very few male plants in his hop yard so that the wind would carry the pollen to all the poles of the yard.

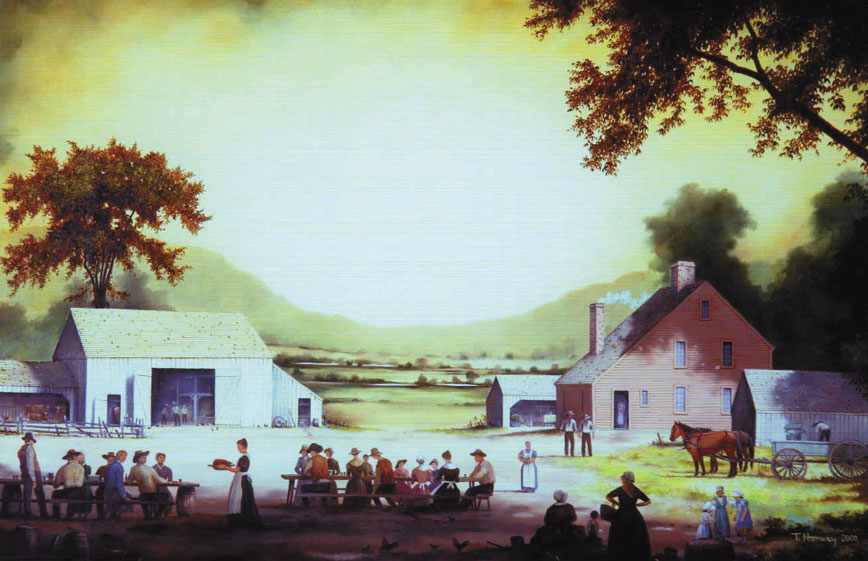

Toward the end of summer my great grandfather would make arrangements to hire people from the neighborhood to help harvest the hops. He usually noted the number of people he hired in his diaries by giving the number of boxes used. The hops were picked into large boxes that were about 30 inches wide, 48 inches long and 30 inches deep. They were set right in the hop yard and the people were paid according to how many boxes they filled.

August 29, 1873 – “Father commenced picking hops today with 2 boxes of pickers. I am to tend box for him. I worked in the forenoon.”

August 27, 1874 – “Father commenced hop picking today with three boxes of pickers. Father has got some very nice girls for hop pickers this year. I had a very pleasant time with them this evening.”

The mature flowers would come off of the hop vines very easily so nearly everyone except the very young children could work at the hop harvest and children could earn what might be their only spending money for the year.

September 6, 1873 – “It is a very pleasant day. We finished picking our hops today. I paid off the pickers and father carried them home. We paid .70 cts a box. Had 82 boxes of hops.”

The box tender was the person who cut the vines from the hill, pulled up the poles and removed the vines near the boxes. The box tender had to be a strong man who could handle the heavy poles. There were usually four people picking at each box.

August 30, 1873 – “I tended hop box today. It is very slow picking this year.”

August 21, 1876 – “Went to Father Newton’s to tend hop box.”

The picking was done during the hot, sticky days of late summer. The boxes were set up under canvas canopies to shade the pickers and the whole process took less than two weeks on my great grandfather’s farm if everything went well and the weather cooperated.

August 30, 1877 – “Commenced picking hops today.”

Even though this was a hot, tedious, tiring job, most everyone in the family looked forward to hop picking. The women cooked large quantities of food for the pickers, stories were told and songs were sung. Dances were held in the evenings and the whole community was invited. It was another of the jobs that was made enjoyable because of the socialization that took place with friends and neighbors. Farm work was for the most part quite routine and quiet, and the farms were quite isolated from neighboring farms. My great grandfather’s family certainly took advantage of any community get-togethers. Nearly all of the holidays were spent partly with the community at socials of some kind or church events that enabled the farm families to get out and visit friends and neighbors. They truly valued their friendships and the community was an important part of their lives. There are several of my family stories about the pranks, fun and flirting at hop time. I’m sure the better parts of the drudgery were remembered in the stories but they did in fact enjoy themselves.

September 1, 1873 – “We picked hops today. It has been a very warm day. There is a hop dance at William Eggleston’s tonight.”

September 5, 1874 – “In the evening I went up to Del Murphy’s to a dance. There was a big crowd there; over forty numbers. Leonard’s pickers were there. I had a good time. Did not get home till most morning.”

September 11, 1877 – “Flora went up and helped Uncle Thomas’ folks pick hops.”

September 12, 1877 – “Flora and me went up and helped pick hops and went down and got my sheep and lambs from Niles in the forenoon.”

June 23, 1875 – “I went down to Milford to the festival held at Albert Barney’s yard. There was a good many there. It went off very nicely. I enjoyed the evening very much. I saw some old friends there.”

When the boxes were filled, the box tender emptied them into burlap hop sacks that were tied and readied to be transported in the wagons to the hop kiln. Every evening the days pickings were dried and stored to make way for the next day’s picking. The hop kiln on my great grandfather’s farm was built in the 1880s a distance from the house so that the sulfur fumes would not drift toward the residence. It was a small kiln (about 15 ft. wide and 30 ft. long) with a simple gabled roof and a cupola over the drying floor.

August 12, 1876 – “I bought sacking for eight hop sacks.”

October 24, 1876 – “I paid Eugene Eggleston .90 cts for sacking.”

As soon as the hops were picked for the day, they were spread on the slatted drying floor that had been covered with burlap hop sacking. Just as soon as the hops were spread evenly, my great grandfather would start a fire in the wood stove that set on the lower level under the drying floor. The stove pipe went out the back of the kiln and up the side of the building, but the heat from the stove rose up through the drying floor and out the cupola on the top. He would start the fire even before chores for the evening, because the drying process could take well into the night and the next day was another busy day in the hop yard. He had to tend the hops constantly by turning them so that they would dry evenly and by keeping the stove going at the desired heat. He would keep a small pot of rolled sulfur on the stove that would burn with a purple glow and release sublimed sulfur and sulfur dioxide that would help to preserve the hops above. Sulfur dioxide has a bleaching affect on the cellulose of plants and is used in a similar fashion today to preserve dried fruits.

September 18, 1876 – “Bought my hop sacking.”

Before the next day began, the hops would be dry and moved through a door to the storage room which was in front of the drying room on the same upstairs level. When enough hops were ready in the storage room, they were sent through a trap door in the floor to the pressing room on the first floor below. The press created a large bale that weighed around 200 pounds and was held together with burlap sacking that was sewn around the bale while still in the press.

September 20, 1876 – “Pressed my hops – 714 lbs.”

November 5, 1877 – “Arthur worked down to Del’s. He took 9 ½ lbs. of fence wire down to Del’s to tie hop sacks with (33 cts. worth at 10 cts per lb.).”

In the 1885 account book of John F. Scott, a hop dealer in Cooperstown, William Cooper was entered as selling 61 bales of hops averaging nearly 200 lbs. each. This was a large production for the size farm and the small hop kiln that he used.

October 20, 1873 – “Helped father press some hops.”

September 21, 1875 – “I helped father press hops in the forenoon and helped Fred set up hop poles in the afternoon.”

October 24, 1877 – “Arthur and I went down to Jerry’s and pressed my hops. Del helped us. I had 14 bales. I had 4 yards of baleing of Del Thomas. Hoose had 7 ½ yards of me.”

October 27, 1877 – “I went to Cooperstown with my hops. Del Hoose drawed a load for me, 7 bales each. They weighed 2509 lbs. Came to $263.44. I paid Jerry Pratt for drying $37.50. The boys delivered mother’s hops to Scott and he would not take them. They stored them in the barn occupied by Emiline Niles.”

October 23, 1877 – “I went down to mother’s and helped the boys press their hops to day. We pressed 10 bales.”

November 1, 1877 – “Irve Hoose paid me $1.12 for hop baleing.”

The resulting bales of pressed hop were sold to the local hop merchants for the highest price that could be found. When the price was low, my great grandfather would hold off on selling in hopes of finding a better price later in the year. Some years he would be selling his hops well into the new year.

October 30, 1873 – “Father and I carried the hops off today. Delivered them at Robert Quails in Cooperstown. There was 1401 pounds of them. They came to $560.40.”

October 19, 1875 – “Father carried some of his hops down to Milford today. Mr. Wilbur bought them.”

November 3, 1877 – “I went to Cooperstown with a load of hops for Del Hoose.”

November 17, 1876 – “Sold my hops to Robert Quail for 30 ½ cts. per pound.”

October 20, 1877 – “I went up to the hop factory grist mill with 11 bushels of wheat. I sold mother’s hops and my own (.10 cts per lb.). Mother’s to Scott to be delivered Thursday, mine to Quail to be delivered Saturday.”

January 5, 1872 – “Father and I went to Cooperstown to sell our hops but could not.”

Hop production on small farms in my great grandfather’s time was very profitable, but it was more than the income that made hop time so popular. It was an exciting time for the whole farm family. Like many other large seasonal jobs on his farm, William Cooper cooperated with neighbors and the whole community, working together to make the very labor intensive methods of the time possible and more manageable. In fact, work in the hop yards was the only work of the year where all individuals (neighbors, relatives, and friends) other than the hop growers immediate family were paid by the amount of work completed. All other cooperative work was done with community bees where people volunteered their help for the food, society, entertainment, and excitement that accompanied the event as well as the understanding that they could count on reciprocal help when they needed it for similar tasks. My great grandfather wrote about corn husking bees, barn and house raising bees, logging bees, bark peeling bees, and threshing bees.

Hop time was special also by the fact that so many people were needed to work in the yards that crews were brought in from all over the state. Many came from large cities to spend some time in the country. This meant that at all of the dances and community events there would be people that would never otherwise visit, and it was expected that all should be in a festive mood. There was singing and joking around the hop boxes and in the evenings the pickers would ride on the farm work wagon around the community to visit and see what other groups of pickers were doing. Several times a week there were hop dances to attend. My family has stories of people who even met their future husbands or wives at hop events. The first entries that my great grandfather made about my great grandmother was when she came to his farm to pick hops in 1874. She was mentioned continually from that time on. So hop time was an exciting change from the usual work.

September 4, 1874 – “In the evening I went over to Mr. Leonard’s and called there to see some of his hop pickers. I took supper with them and had a good time and lots of fun. Two of the girls went out riding with me and had a very pleasant time. I did not get home until the small hours of the night.”

September 8, 1874 – “I stopped at Jud Cornish’s hop yard on my way home for a few minutes to see his hop girls.”

September 11, 1874 – “I worked for Hiram today – tended hop box. It is excessively warm today. We got along over the yard pretty fast today. This evening I went to a dancing party at Judson Cornish’s. There was not a great many there, but what were there enjoyed themselves very well. I think I did at least and the company was good, and everything went off nicely. I came away about midnight. They were still dancing when I left. I particularly made the acquaintance of two young ladies tonight.”

September 12, 1874 – “Saw the Scott girls tonight. They had just returned from hop picking. Said they had a splendid time.”

As the fires were set in the Cooper hop kiln in the latter days of summer, the family worked longer, more exhaustive days during what they considered an enjoyable break from their routine farm work. The evening breezes would drift the plume from the kiln stack over a landscape rich with the ripening fields that my great grandfather labored over. As the sun sank lower, everything would take on a golden flush of the sunset. The neighborhood was more active than ever. Hop pickers were busy socializing, traveling to and from dances and hop yard visitations in the glow of the evening light. The entire community was very closely tied to the land and what grace it afforded them. Every once in a while my great grandfather would write with a flourish that would hint of his appreciation for this land he toiled upon.

September 26, 1874 – “It is a lovely moon light evening – so warm and pleasant riding.”

May 26, 1873 – “I got up before sunrise this morning and started for Hiram’s. The birds were singing very sweetly this morning. I and Hiram ploughed out hops today.”