Growing and Marketing Muskmelons

Growing and Marketing Muskmelons

by J.W. Lloyd, Chief in Olericulture

reprinted from 1933 Illinois Extension Circular 405

This older material offers some excellent elemental information on melon growing. I found the notes on how melons might be incorporated into crop rotations to be interesting. Please keep in mind that at the time of this writing certain disease resistant strains of Muskmelon or Cantaloupes we not yet available. Also some of the notes on marketing may be limited. We hope this information is of some help and interest to you. LRM

Selecting the Field

Muskmelons should be planted in a soil that is well drained and that contains an abundance of humus and readily available plant food. If these conditions are met, it matters little what the particular type of soil may be. The crop is grown successfully on the light sandy soils of watermelon regions, the gray silt and yellow silt loams of southern Illinois, and the dark-colored silt loam of the corn belt.

A knoll or ridge sloping gently to the south and protected by timber on the north and west furnishes an ideal site for melons. Such a location will usually produce earlier melons than a north or west slope and is better than a level area because the soil dries out more quickly after a rain, thus permitting more timely tillage in a wet season and resulting in the production of melons of better flavor. It is only in dry seasons that low, flat land, unless thoroughly tile-drained, produces good melons.

The condition of the soil with reference to its supply of humus has a marked influence upon the welfare of the melon crop. Because of its abundance of humus, newly cleared timber land is well adapted to melon culture, but it is difficult to work on account of the stumps and roots. Land slightly deficient in humus can be put in condition for growing melons by plowing under a clover sod, a crop of cowpeas or rye, or a coat of manure applied broadcast.

If melons are to be grown as one of the crops in a regular rotation, they should follow the leguminous crop that is grown for the purpose of adding humus and nitrogen to the soil. In regions where winter wheat and clover are grown, a rotation of wheat, clover, and melons is highly satisfactory. Another good rotation is oats, clover, melons, and corn. In regions where clover does not thrive and wheat and oats are not grown, a rotation of corn, cowpeas, and melons may be employed, or the rotation extended by seeding to grass after the melons are harvested.

If sod land is to be used for melons it should be plowed in the fall.

Liberal Fertilizing Necessary

Muskmelons require liberal fertilizing with readily available plant food. Experiments conducted in various parts of Illinois indicate that well-rotted stable manure applied to the hills before planting may be considered the basic fertilizer treatment for melon production in this state. Yields were somewhat increased by supplementing this treatment with some form of phosphorus such as steamed bone meal or rock phosphate, but often the increased yield did not offset the increased cost for fertilizer. Likewise, an application of manure broadcast in addition to that in the hills increased the yields but at a large additional expense. Considerable increase in yield and in profit was secured from the use of limestone when melons were grown on somewhat acid soil.

On market-garden soils that have been made exceedingly rich by repeated applications of manure, fairly good crops of melons can be grown without special treatment of the hills, but manuring in the hills usually gives the plants a more vigorous start and is likely to result in better yields of early melons than broadcast manuring. Some of the highest yields in experimental tests were secured from manuring both broadcast and in the hills, but the expensiveness of this treatment made it less profitable than manuring in the hills alone.

Preparing Manure for the Hills. Manure for use in melon hills should be ricked up in the fall in long, low piles about 8 feet wide and 2 or 3 feet high. Make the sides of the pile as nearly perpendicular as possible and flatten the top so that rains will soak in instead of running off. Sometimes a layer of dirt about 3 inches deep is placed on top of the manure to help retain the moisture.

Begin work on the manure early in the spring to put it in condition for use. Cut down the pile; turn, and mix the manure until it is thoroughly decomposed and of fine texture. Formerly this work was done by hand with a fork, entailing a large amount of labor. A less expensive method is to turn and mix the manure with a disk and plow. Work the pile three or four times at intervals of one or two weeks.

Time of Planting

The melon is a warm-season crop, and unless the soil is warm and the weather favorable, the seeds will not germinate nor the plants grow. It is therefore usually unwise to plant in advance of the normal season in the hope of securing an early crop. Occasionally such plantings do well, but usually the stand is poor, necessitating much replanting and the early plants which do survive are likely to be so badly stunted by reason of the cool weather that they do not mature their crop much in advance of the later plantings which have had the benefit of warm weather from the start.

Under normal seasonal conditions, planting may be safely begun the first week in May in the southern part of the state, about May 15 in the central part, and May 25 in the northern part. Usually planting in all parts of the state should be completed before June 1, for late plantings in the southern part of the state are likely to be overtaken by excessively hot, dry weather, and in the northern part of the state by early fall frosts.

Sometimes the earliest plantings are protected by “hotkaps” or other plant protectors placed over the individual hills, but this practice is not common in Illinois.

Preparing the Field

Plow the melon ground early in the spring, or replow it if it was broken in the fall. After the ground is plowed, thoroughly pulverize it with a disk or harrow, or both, and then keep it in good, friable condition by an occasional working until planting time arrives. Shortly before planting is to begin, furrow the field out both ways with a single-shovel plow or a turning plow. Make the furrows about 6 inches deep and as far apart as the hills are to be placed. On some soils melon vines make only a moderate growth and may be planted as close as 4 feet apart each way; but on rich soil, where they make a stronger growth, they should be at least 5 feet apart each way and in some cases 6 feet.

After the land is furrowed, apply the rotted manure at the intersections of the furrows. Three or five rows are usually manured at a time, the wagon straddling the middle row (Fig. 1). Use from a quart to a half-peck of manure for each hill, depending on the quality of the manure and also on the quantity available. About 2 quarts is a fairly good application. Drop the manure into the bottom of the furrow, and either mix thoroughly with the soil there and cover with a layer of pure soil in which to plant the seed, or merely cover with the soil without any mixing. The latter method seems to give fully as good results as the former, especially when a small quantity of manure is used, and it is a great saving of labor. In either case, take special care to compact the soil over the manure so that when the seed is planted it will not suffer from lack of moisture by reason of any vacant air space in or about the mass of manure. Sometimes the manure is covered with soil by merely plowing a furrow on each side of the furrow containing the manure, but unless the soil is in exceedingly fine condition, this method is not so satisfactory as using a hoe and giving each hill individual attention.

In making the hill, some planters compact the soil with a hoe, while others use their feet. The extent of compacting advisable will depend upon the type of soil and the amount of moisture it contains. When ready for planting, the hill should be practically level with the general surface of the field. If too low, the hill will become water-soaked in case of rain and the seeds or plants will be injured; if too high, there is likely to be insufficient moisture to insure proper germination and growth.

Planting the Seed

If the hills have been made more than a few minutes before the seed is dropped, scrape the top layer of dry soil aside with a hoe so that the seed may be placed in immediate contact with the moist soil. The area thus prepared should be at least 6 inches across and should be smooth and level. Scatter 8 or 10 seeds uniformly over this area, and cover with about half an inch of fine, moist soil. Firm with the back of the hoe and cover with a sprinkle of loose dirt to serve as a mulch. If a heavy rain packs the top soil and a crust is formed before the plants appear, go over the field and carefully break the crust over each hill by means of a garden rake.

The method of preparing the hills and planting the seed described above applies to field rather than garden conditions and to soils of medium rather than excessive fertility. In a market garden, where the soil is exceedingly rich as a result of repeated manuring for onions or cabbage and is in fine tilth, melon seed is commonly sown with a garden seed drill in drills 6 to 8 feet apart without any special preparation of the soil where the plants are to stand and without application of fertilizing material other than manure applied broadcast before plowing.

One pound of seed is considered sufficient for planting an acre of melon in hills, while 2 or 3 pounds are required for drill planting.

Thinning the Plants

While 8 or 10 seeds are planted to a hill for the sake of insuring a full stand, only two, or at most three, plants are left to make the crop. Thinning is usually deferred until the plants have become fully established and the worst part of the struggle against the striped beetle is over. However, the plants must be thinned before they begin to crowd badly, or those that are to remain will be stunted. Sometimes two thinnings are made.

Thinning is usually completed by the time the plants have four rough leaves. If the seed has been well scattered in planting, so that each plant stands by itself, the superfluous plants may then be pulled with the fingers, but extreme care must be taken to avoid disturbing the roots of the remaining plants. Sometimes the plants are cut off with a knife or shears, instead of being pulled, and thus all danger of disturbing the roots is avoided.

If the seeds have been sown with a drill, as in market- garden practice, the plants are usually thinned to one in a place at distances of 2 to 2-1/2 feet in the row.

Transplanting for Early Crop

Since it is impossible to increase the earliness of the melon crop to any great extent by early planting in the field, growers at certain points in the state have adopted the transplanting method. The seed is planted in a hotbed three or four weeks earlier than would otherwise be feasible and the plants grown under controlled conditions of temperature and moisture during their most critical period. This method simplifies the matter of protection from striped beetles. The main objections are the expense for sash and the difficulties attending transplanting.

A melon plant will not survive transplanting if the root system is disturbed. For this reason the seed is sown on inverted sod, in pots, or in dirt bands. The dirt bands are used almost exclusively by commercial growers. They may be of either wood or paper. The wooden bands are thin strips of veneer 3 inches wide and 18 inches long scored at intervals of 4 inches so that they can be bent without breaking. As a further precaution against breakage, they are soaked in water for a few hours before being used. When folded ready for use, each band resembles a small strawberry box without a bottom.

Place the bands close together in a hotbed and fill them level full with fine, rich soil. With a block of wood shaped for the purpose, press the soil within the bands until it is 1/2 to 3/4 inch below the top of the band. If only part of the dirt is put in at first and is pressed down firmly, and then the rest of the dirt put on and pressed, the soil in the band will be more compact throughout and will hold together better in the transplanting than if the dirt is pressed only once. Unless the soil used is very moist, thoroughly water the bed. Next place three seeds in each band. Cover with fine, moist soil deep enough to fill the band. Do not firm this soil.

The hotbed for melon plants should have full exposure to light and be maintained at a high temperature – about 85 degrees F. during the day and 65 to 70 degrees at night. Give as much ventilation as the weather will permit. Avoid overwatering.

As soon as the plants are well started, they are usually thinned to two in a band by cutting off the extra plant with a sharp knife.

About four weeks after the seed has been planted, the plants should be in the right condition for transplanting to the field. They are then compact and stocky, with about four rough leaves. If allowed to remain longer in the bed, they begin to stretch for light and are of little value for transplanting, for the long naked stems, unable to support themselves and unaccustomed to direct sunlight, are easily sunburned and the plants seriously checked if not killed outright.

When the plants are ready for the field, thoroughly water the bed and with a spade lift the bands enclosing the masses of earth and plant roots and place them close together on the platform of a low wagon. Then drive the wagon to the field, where the hills have previously been prepared by mixing rotted manure with the soil as already described, except that the mixture of soil and manure usually extends to the surface. Open the hills with hoes or a plow just ahead of the planters. When a plow is used, it may be necessary to follow with hoes to remove the lumps from the bottom of the furrow at the point where each plant is to be set. Set five rows across the field at a time, the team straddling the middle row. Lift the plants from the wagon either by hand or with the aid of a flat trowel made for the purpose, and carefully place them in the hills, band and all. Take care that the bottom of the mass of earth within the band is in close contact with the soil of the hill. Then carefully remove the band and draw in fine, moist soil about the mass of earth containing the plant.

Cultivation

Whether the melons are transplanted from a hotbed or grown from seed planted in the field, the tillage of the crop should begin as soon as the plants can be seen. In the case of transplanted plants, this will be the same day that they are set in the field.

The early tillage should be deep and as close to the plant as it is feasible to run the cultivator. The object of this deep tillage is to establish a deep root system so that the plants will not suffer so severely from dry weather later in the season. In the case of a field-planted crop, it is not feasible to cultivate so close to the plants early in the season because of the danger of tearing out the small plants. For this deep tillage a one-horse, five-shovel cultivator, often weighted with a rock, is the tool most commonly used. It is customary to follow this with a “boat” (Fig. 2) or a 14-tooth cultivator to pulverize the soil more fully.

Tillage is usually given after each rain, or at least once each week, so that the soil is maintained in a loose, friable condition. In addition to the cultivation with a horse, much hand-hoeing is required close about the plants. Break any crust forming after a rain and draw up fresh, moist soil about the plant. Remove by hand any crab grass and weeds appearing in the hill.

Tillage is ordinarily stopped and the crop laid by as soon as the vines run enough to interfere with the cultivator. However, the vines are sometimes turned and kept in windrows so that tillage can be continued until the picking season opens. This greatly facilitates the harvesting of the melons, since the pickers do not have to wade through weeds and vines wet with dew nor injure the vines by tramping. Also, if spraying becomes necessary, it is much more readily done if the vines are thus trained in rows.

Enemies and Obstacles

In the northern part of Illinois, the melon crop is practically free from serious enemies, with the exception of the striped beetle. In very dry season, the melon louse also may cause damage, and the wilt may occur to a limited extent. In the southern part of the state, however, the crop is likely to be harassed from the time the seed is planted until the last fruit is harvested. The leading enemies of the crop in this section will be considered in approximately the order of their appearance.

Field Mice. The night after the seed is planted in southern Illinois fields, a large part of it may be dug up and destroyed by field mice. If the seeds in each hill have been planted close together, the hills that are attacked are usually destroyed completely, but if they have been scattered as previously advised, some seeds may escape. However, in regions where mice are at all abundant, some additional precaution is necessary in order to insure a stand of plants.

Striped Beetles. The small yellow-and-black striped beetle which commonly attacks cucumbers, melons, and squashes may be expected in the melon patch every year in all parts of Illinois, though the severity of the attack varies greatly in different seasons and different places. Usually the plants are attacked as soon as they appear aboveground, and unless prompt treatment is given, the entire plantation is likely to be destroyed by these beetles.

When the plants are grown in a hotbed, the beetles often do not find them.

Moles. In the southern part of Illinois, about the time the plants are past danger from the striped beetles, moles begin burrowing through the field. They follow the melon row, loosening up the soil under the hills. This lets in the air about the roots so that the vines wilt and die. One mole can thus do a large amount of damage if allowed to continue his work through the season. The best way of dealing with moles is to keep two or three mole traps in the field and set them wherever a fresh burrow appears.

Lice. The melon louse, or aphis, is likely to attack the plants about the time the vines commence to run. Usually the first attack is confined to a few hills, which may be in various parts of the field. Unless prompt treatment is given, the insects spread rapidly to adjoining hills and may be distributed throughout the field by the time the first fruits have set. These insects feed upon the underside of the leaves, causing them to curl. They suck the juice from the plant and render the vine so weak that the quality of the fruit is seriously impaired. In case of a severe attack, especially in dry weather, the vine may be completely killed.

Various methods have been employed in attempts to control these insects. A common practice has been to watch carefully for the earliest signs of infestation, when only a few hills are involved, and to give special treatment to these hills in order to prevent the spread of the insects to adjoining hills.

Under normal conditions the natural enemies of the aphis, notably the lady beetles, will do much to keep this insect in check. But in case of a severe attack neither the lady beetles nor any single-hill treatments seem capable of preventing damage. One serious defect in single-hill treatments is that usually only those hills which show considerable infestation are treated, and slightly infested hills serve as sources of continued infestation.

Wilt. The sudden wilting of individual vines scattered about the field, if no moles are present, is usually due to a bacterial disease commonly designated as “wilt.” This disease is usually most evident after the crop has set and the fruits are at least partially netted. Sometimes the fruits are so nearly mature that they ripen, but they are always of a springy consistency and entirely unfit for shipping. Unfortunately there is no direct remedy known for this disease. The control of the striped beetle may indirectly contribute to the control of the disease, however, since the striped beetles are supposed to carry it from one plant to another. The infected plants should be removed and burned or deeply buried as fast as they appear.

Rust. After the melon crop has escaped the ravages of mice, beetles, moles, lice, and wilt, and the melons are almost ready to harvest, a fungous disease known as the “rust” is likely to cause the foliage to collapse and the melons to ripen prematurely without the proper development of netting or flavor. This disease appears first as small, circular, brown spots on the leaves. The spots gradually increase in size and number until finally they run together and the entire leaf becomes brown and dead. The oldest leaves, at the center of the hill, are the first to be attacked, and the infection gradually spreads outward until all the foliage is involved. If the leaves die before the melons ripen, the fruits do not develop normally and are decidedly deficient in both netting and flavor.

If rust-resistant varieties of muskmelons are planted instead of the susceptible varieties, spraying for rust control is unnecessary. Several such varieties are now available through the regular seed trade.

Floods. In addition to damage by insects, mice, moles, and plant disease, there are other obstacles encountered in producing a melon crop. The melon suffers severely from extremes in the moisture supply. An excess of moisture can be largely avoided by planting on well-drained land, as suggested above; but if the rain falls in torrents, as it often does in the melon regions, the soil is washed along the hillsides and many vines and melons are partially buried in the mud. Sometimes entire hills of melons are destroyed in this way, but usually most of them can be saved by systematically digging them out. If a melon fruit is allowed to remain partially buried, the part that is underground does not develop properly and will be of poor flavor. In fact, if melons are being grown for a select trade and the season is wet, it may be necessary to go over the field repeatedly and move each melon out of the pocket of mud which has been made about it by the rain; for the smaller the point of contact of the melon with the earth, the more nearly will the lower side equal the upper in flavor. The old gardener’s practice of inserting a shingle or piece of slate under each melon for the sake of improving its flavor is not without foundation.

Drouth. While excessive rainfall is unfavorable to the proper growth and development of muskmelons, and comparatively dry weather at the time of maturity is considered essential to the production of melons of the highest quality, yet muskmelons will not withstand severe drouth. Extremely dry weather associated with excessively high temperature, especially if these conditions obtain before the melons are netted and continue for a considerable time, will sometimes cause melons to ripen prematurely without properly netting and to be of little commercial value. In an unirrigated region little can be done to help the crop under such condition, though the effects of an ordinary drouth can be largely overcome by continuing tillage until late in the season.

Varieties

Two distinct types of muskmelons are grown in Illinois, the large-fruited and the small-fruited. The large-fruited type includes the Hackensack and Ohio Sugar (green-fleshed) and the Osage, Tip Top, Bender’s Surprise, and Milwaukee Market (salmon-fleshed). Melons of this class are grown principally by market gardeners located within hauling distance of their respective markets or by watermelon growers as a side line. In either case they are usually handled in bulk and sold by the melon or by the dozen. Occasionally melons of this type are packed in crates and shipped to the general market.

Most of the muskmelons grown in Illinois for shipment to the large city markets are of the small-fruited type. Formerly the green-fleshed varieties were preferred, including various strains developed at Rocky Ford, Colorado, such as the Eden Gem, Early Watters, and Pollock Ten-Twenty-Five. At the present time, however, preference is shown for the salmon-fleshed melons, including Hale’s Best, Hearts of Gold, and Superfecto. These melons are grown to some extent for local markets also.

A new variety of melon, intermediate in size, that recently has been attracting much attention for local market and has also been shipped to some extent is the Honey Rock or Sugar Rock. It is a salmon-fleshed variety of very high quality.

Seed

No matter what variety of melon is grown, it is extremely important that pure seed be planted if good melons are to be produced. The melon deteriorates very rapidly under careless methods of seed selection. None but the very choicest specimens from productive vines should be selected for seed. It is unsafe to cut seed from a field in which more than one variety of melon is grown, for seed from such a field would likely be very badly mixed and the product undesirable for market.

If a grower has sale for all his good melons, it may be cheaper for him to purchase his seed than to save it. But here again there is danger of procuring inferior seed, for much of the melon seed on the market is cut without careful selection in order to meet the demand for cheap seed. Even cull melons are used to supply this demand. Such seed is expensive at any price. The difference in the cost of good and poor seed is insignificant when compared with the advantages to be derived from the use of seed which can be depended upon to produce melons of a given type.

Picking

It is important that melons be picked at the right stage of maturity. The riper they can be allowed to become while still on the vines, and yet be sufficiently firm to reach the market in desirable condition, the more acceptable their flavor will be. The farther from market they are produced, the less mature they must be when picked. Expert discrimination is necessary to pick melons at such a degree of ripeness that they will reach the market in firm condition and yet possess the desired flavor.

The condition of the vines and the rapidity of ripening of the melons in the field will have a bearing upon the stage of maturity at which they should be picked. Early in the shipping season, when the vines are in full vigor and the melons ripening slowly, the fruits may safely be left upon the vines until more mature than would be safe later in the season when the plants have become somewhat weakened, or when by reason of excessive heat, the melons are ripening very rapidly. Melons should not be picked at the same degree of maturity under different conditions of ripening, methods of transportation, and distances from market.

No rule can be given for picking melons that will apply under all circumstances; the grower must exercise judgment in reference to each day’s picking. Under ideal marketing conditions, the melons will reach the market in the best condition if picked as soon as a definite crack appears about the stem. The fruit can at that time be readily separated from the vine by slight pressure upon the stem with the thumb or finger. Some growers have a tendency to pick considerably before this point has been reached, in order to run no risk of the melons becoming soft in transit. This maybe necessary in very hot weather or at points where refrigerated transportation is not available. However, much more skill is required to pick melons before they will part readily from the stem, and there is always the risk of picking them so green that they will be very deficient in flavor. It has been estimated that 10 percent of the melons shipped to the large city markets are picked so green that they never become edible.

In order that the melons may have any degree of uniformity in ripeness it is essential that the plantation be picked over every day, and at the height of the season the ripening may be so rapid as to necessitate picking twice a day.

Grading

In varieties of melons that normally develop considerable netting, there is a close relation between the amount and character of netting and the quality of a melon. This makes it possible, after a little experience with a given variety, to grade melons with extreme accuracy as to quality, on the basis of netting. As a rule, the denser and more fully developed the netting, the better the quality of the melon.

Marketable melons may usually be grouped advantageously into two grades, especially for local markets. These may be designated as “No. 1” and “No. 2,” though the official grades for shipping melons, recommended by the U.S. Bureau of Agriculture Economics, are designated as “No. 1” and “Unclassified.” The latter grade is not described but is said to consist of melons not graded as No. 1.

No. 1 melons should be well netted for the variety (Fig. 4), well formed, of the right degree of maturity for the intended market, and free from aphis honey dew, cracks, and other serious defects. Specimens with less netting, but in which the netting is fairly well developed for the variety, may be placed in a second grade for sale at a lower price. Melons in which the netting is very poorly developed, as well as those which are misshapen or very small, should be classed as culls. Cracked and over-ripe specimens must also be graded as culls even though of fine quality, for they would be likely to spoil before reaching the consumer.

No melons should be graded as No. 1 which are not of high eating quality. As the season advances and the vines become somewhat weakened, more and more severe grading on the basis of netting must be practiced. All through the shipping season, a few melons should be cut and tested each day, so that the basis of grading may be changed as conditions warrant.

Packing

Melons intended for shipment are usually packed in slatted crates. The crates most commonly used in Illinois at the present time are flat crates made for one layer of melons. Some growers use flats of the same dimensions as those recognized as standard packages for shipping melons from the western states, namely, 4″ x 12″ x 22-1/2″, 4-1/2″ x 13-1/2″ x 22-1/2″, and 5″ x 14-1/2″ x 22-1/2″, inside measure. Others use crates 4-1/2″ x 13″ x 20″ or 5″ x 14″ x 20″, inside measure, made in local Illinois factories.

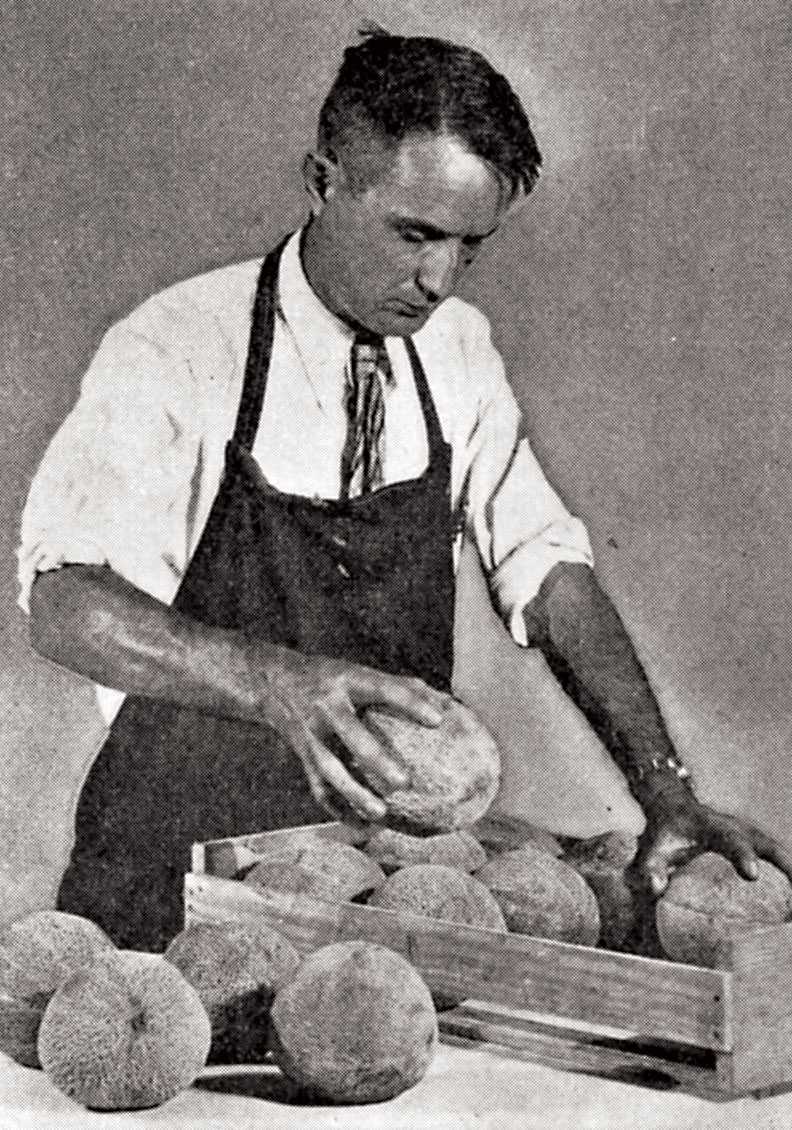

The melons in a given package must be fairly uniform in size, arranged in an attractive manner, and so packed that each specimen will remain in the exact position where it was placed by the packer. The packing must be tight and yet the melons must not be bruised by being jammed into place.

There is a definite arrangement in the crate for melons of each size. Each melons should be placed on its side, with its longest axis extending lengthwise of the crate (Fig. 5). The appearance of the product on the market will be greatly enhanced if special care is taken in placing the specimens in the package.

Selling the Crop

After the melon crop has been carefully picked, graded, and packed, success in its marketing depends upon placing the product in a profitable market. Three general methods of marketing are open to the Illinois grower: shipping by express or truck to dealers in the smaller cities, shipping by freight to commission men in large cities, and selling locally, either to dealers or at a roadside market.

The most satisfactory way of supplying melons to the markets of the smaller cities is to arrange with one high-class retailer in each city to handle a certain number of packages of a given grade each day through the shipping season. In this case each shipment of melons is usually billed out at a price set by the grower rather than the dealer. In this way it is often possible to build up a very satisfactory trade in high-grade melons. The most serious drawback to the method is the impossibility of determining the number of packages that can be furnished each day and hence the necessity of limited orders to the supply that can normally be furnished. Some other way must then be found to market the rest of the crop. When the pickings are heavy, the surplus is usually consigned to some commission man located in a small city other than those in which retail dealers already being supplied are located.

The safest plan to follow in shipping melons to a large city market is for the grower to make arrangements with some trustworthy commission firm to handle his entire product. This should be done before the shipping season begins. If the grower can visit the market and talk personally with his commission man, much will be gained. The grower and the commission man should have a specific understanding regarding the grading and packing of the melons, and regarding the meaning of the different brands to be used on the packages, so that the salesman may know with absolute certainty the exact character of the goods contained in a given package. The salesman will thus be able to place the different grades with the different classes of trade, and thus realize for the grower the largest possible proceeds from the entire product.

Muskmelons of high quality may be sold very advantageously at a roadside market, either as the only product being sold in a temporary market established for the purpose, or as a leader during the melon season in a more or less permanent market.

For roadside marketing the melons should be as carefully graded as for shipping, and the different grades and sizes displayed separately. It is well to have the melons neatly piled in quite large quantities on benches or tables so as to make an impressive display. If only melons of good eating quality are offered, a very good roadside business can be developed in many localities.