Propagation by Means of Budding and Grafting Part 4

Propagation by Means of Budding and Grafting

taken from The Nursery Manual (1934) by Liberty Hyde Bailey

The veneer-graft

A style of grafting much used, particularly for ornamentals and for rare stocks grown in pots, is seen in Fig. 164. An incision is made on the stock just through the bark and about an inch long (A), the bit of bark being removed by means of a downward sloping cut at its base. The base of the cion is cut off obliquely, and on the longest side a piece of bark is removed, corresponding to the part taken from the stock. The little tongue of bark on the stock covers the base of the cion when it is set. The cion is tied tightly to the stock (B), usually with raffia.

This method of grafting makes no incision into old wood, and all wounded surfaces are completely covered by the matching of the cion and stock. It is not necessary, therefore, to wax over the wounds, as a rule. If used in the open, however, wax should be used. The parts grow together uniformly and quickly, making a solid and perfect union, as shown at D. So far as the union of the parts is concerned, this is probably the most perfect form of grafting. This method, which is nothing but the side-graft of the English gardeners with the most important addition of a longer tongue on the stock, is known by various names, but it is oftenest called veneer-grafting in this country.

Veneer-grafting is employed mostly from November to March, on potted plants. Stocks grown outdoors are potted in the early fall and carried over in a cool house or pit. The cion is applied an inch or two above the surface of the ground, and the stock need not be headed back until the cion has united. (See Fig. 165.)

Both dormant and growing cions are used. All plants in full sap must be placed under a frame in the house, in which they may be almost entirely buried with sphagnum, not too wet, and the house kept cool and rather moist until the cions are well established. Some species may be transferred to the open border or to nursery rows in the spring, but most plants grafted in this way are handled in pots the following season. Rhododendrons, Japanese maples and many conifers are some of the plants multiplied by veneer-grafting. Such plants are usually laid on their sides in frames and covered with moss for several days, or until healing begins.

This method, when used with hardy or tender plants, gives a great advantage in much experimental work, because the stock is not injured by a failure, and can be used over again many times, perhaps even in the same season; and the manipulation is simple, and easily acquired by inexperienced hands.

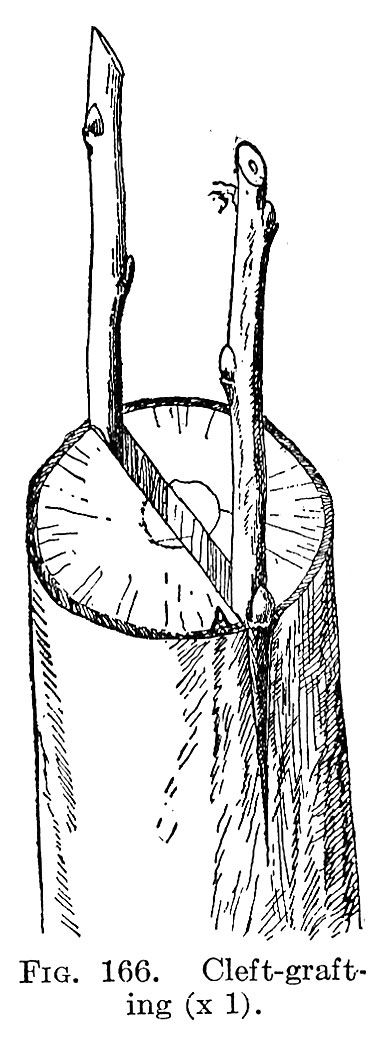

The cleft-graft

In cleft-grafting, the stock is cut off squarely and split, and into the split a cion with a wedge-shaped base is inserted. It is adapted to large stocks, and is the method employed for top-grafting old trees, its only competitor being the bark-graft. Figs. 166, 167 illustrate the operation.

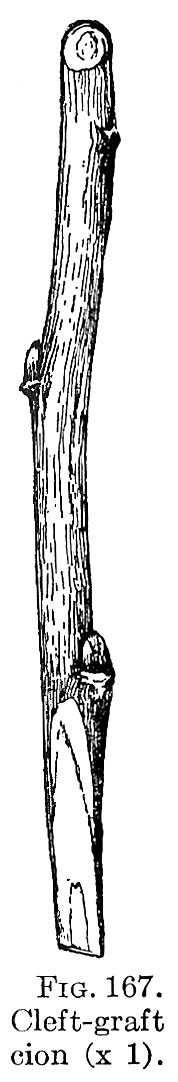

The end of the stock, technically called a “stub,” is usually large enough to accommodate two cions, one on either side. In fact, it is better to use two cions, not only because they double the chances of success, but because they hasten the healing of the stub. Cleft-grafting is at best a harsh process, especially on large limbs, and its evils should be mitigated as much as possible by choosing small limbs for the operation. In common practice, the cion (Fig. 167) bears three buds, the lowest one standing just above the wedge. This lowest bud is usually entirely covered with wax, but it pushes through without difficulty. In fact, being nearest the source of food and most protected, its chances of living are greater than those of the higher buds.

The sides of the cion must be cut smooth and even. A single draw cut on each side with a sharp blade is much better than two or three partial cuts. A good grafter makes a cion by three strokes of the knife, one to cut off the cion and two to shape it. The outer edge of the wedge should be a little thicker than the inner, so that the stock will bind on it and hold it firm at the point where the union first takes place. The twigs from which the cions are made are taken in late fall or winter, or very early spring, and are kept as directed earlier.

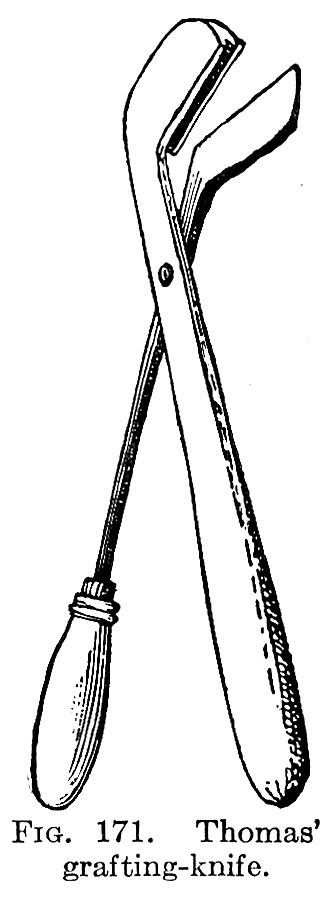

The stock or stub must be cut off square and smooth with a sharp and preferably fine-toothed saw. If one desires to be specially careful in the operation, the end of the stub, or at least two opposite sides of it, may be dressed off with a knife, so that the juncture between the bark and the wood may be more easily seen. Professional grafters rarely resort to this dressing, however. The stub is then split to the depth of 1-1/2 or 2 inches. Various styles of grafting-knife are used to split the stub. One of the best ones is shown in Fig. 168. It is commonly made from an old file by a blacksmith. The blade is curved, so that the bark of the stub is drawn in when the knife is entering, thereby lessening the danger of loosening the bark. Another style of knife is illustrated in Fig. 169. In this tool, the cutting edge is straight, and, being thinner than the other tool, tends rather to cut the stub than to split it. On the end of these knives is a wedge, about 4 or 5 inches long, for opening the cleft. The wedge is driven into the cleft and allowed to remain while the cions are placed. If the cleft does not open wide enough to allow the cions to enter, the operator bears down on the handle. It is important that the wedge stand well away from the curved blade in the knife shown in Fig. 168, else it cannot be driven into the stub. In Fig. 169 — showing the style of knife commonly seen in the market — the wedge is too short for most efficient service.

There are various devices for facilitating the operation of cleft-grafting but none of them has become popular. One of the best is Hoit’s device (Fig. 170), which cuts a slot into the side of the stub. The machine is held in place by a trigger or clamp working in notches on the under side of the frame. The upper handle is then thrown over to the right, forcing the knife into the stub. This is a Californian device. A very good grafting-knife for small stocks or trees in nursery row is the Thomas knife shown in Fig. 171. The larger arm is made entirely of wood. At its upper end is a grooved part, into which the blade closes. This blade can be made from a steel case-knife, and it should be about 2-1/2 inches long. It is secured to an iron handle. The essential feature of this implement is the draw cut, which is obtained by setting the blades and the pivot in just the position shown in the figure. The stock is cut off by the shears, and the cleft is then made by turning the shears up and making a vertical cut. The cleft, therefore, is cut instead of split, insuring a tight fit of the cions. This tool is said to be specially useful on hard and crooked grained stocks.

In cleft-grafting, the cions must be thrust down to the first bud, or even deeper, and it is imperative that they fit tightly. The line of separation between the bark and wood in the cion should meet as nearly as possible the similar line in the stock. The cions are usually set a trifle obliquely, the tops projecting outwards, to insure the contact or crossing of the cambium layers. Writers often state that it is imperative to have the exact lines between the bark and wood meet for at least the greater part of their length, but this is an error. The callus or connecting tissue spreads beyond its former limits when the wounds begin to heal. The most essential points are rather to be sure that the cion fits tightly throughout its whole length, and to protect the wound completely with an air-tight covering. The practice must be modified, of course, to suit the stock and the occasion.

Sometimes rooted cuttings of grapes are cleft-grafted (Fig. 172), and these, being in the ground, are well protected, and it is difficult to split the stub deep enough to allow the cion to be thrust in far. If the stub, in this case, has little elasticity after being split, it should be tightly wound to keep the cion in place. An old grape stock, cleft-grafted, and then covered with earth, is seen in Fig. 173. These covered grape stubs are usually not waxed. This is the common, and generally the best, method of grafting the grape.

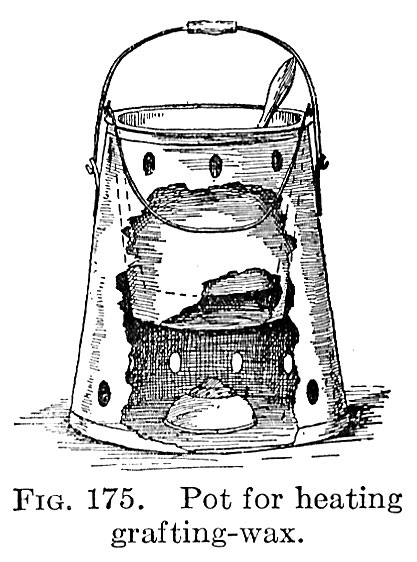

The wounds must now be covered with wax. Fig. 174 is a stub after the covering has been applied. If the grafting is performed in early spring, when the weather is cold, the wax will have to be applied with a brush. The wax is melted in a glue-pot, which is carried to the tree. But if the weather is warm enough to soften the wax, it should be applied with the hands. The hands are first greased to prevent the wax from sticking. The two side or vertical portions are applied first. The end of the mass of wax in the hand is flattened into a thin pad about a half inch wide. This pad is then laid over the lower bud of the cion and held there by the thumb of the other hand, while the wax is drawn downwards over the cleft, being pressed down firmly upon the bark by the thumb of the first hand. The wax gradually tails out until it breaks off just below the lowest point of the cleft. The flattened upper part is then wrapped around the cion from either side, completely and tightly encircling it. A simple deft wrapping of the wax about the cion makes a tighter joint than can be secured in twice the time by any method of pinching it into place. Another pad of wax is now flattened and applied over the end of the stub. Most grafters apply a bit of wax to the tops of the cion also. All the wounds must be covered securely.

For applying the wax warm, a heater is needed. A good form is shown in Fig. 175 (Peck, Cornell Reading-Course Lesson). The wax is in the top receptacle, standing in a dish or pail of water. In the bottom is a lamp to supply the heat.

Top-working trees by means of the cleft-graft.

Cleft-grafting is employed not so much to multiply the plant as to change a tree from one variety to another. It is the form of grafting used in old apple and pear orchards, and it may be employed on plum and many other trees. The top-grafting of large trees is an important operation, and many men make it a business. These men usually charge by the stub and warrant, the warrant meaning that one cion of the stub must be alive at counting time in late summer. A grafter in good “setting” can graft from 400 to 800 stubs a day and wax them himself. Much depends on the size of the trees, their shape and the amount of pruning before the grafter can work in them handily. Every man who owns an orchard of any extent should be able to do his own grafting.

An important consideration in the top-grafting of an old tree is the shaping of the top. The old top is to be removed in three or four or five years, and a new one is to be grown in its place. If the tree is old, the original plan or shape of the top will have to be followed in its general outlines. The branches should be grafted, as a rule, where they do not exceed an inch and a half in diameter, as cions do better in such branches, the wounds heal quickly, and the injury to the tree is less than when very large stubs are used. The operator should endeavor to cut all the leading stubs at approximately equal distances from the center of the tree; and then, to prevent long and pole-like branches, various minor side-branches should be grafted. These will serve to fill out the new top and to afford footholds for pruners and pickers. Fig. 176 is a good illustration of an old tree just top-grafted. Many stubs should be set, and at least all the prominent branches should be grafted if the tree has been well-trained. It is better to have too many stubs and to be obliged to remove some of them in after years, than to have too few. In thick-topped trees, care must be exercised not to cut out so much foliage the first year that the inner branches will sunburn. All large branches which must be sacrificed ought to be cut out when the grafting is performed, as they increase in diameter very rapidly after so much of the top is removed.

A horizontal branch lying directly over or under another should not be grafted, for it is the habit of grafts to grow upright rather than horizontal in the direction of the original branch; and it is well to split all stubs on such branches horizontally, that one cion may not stand directly under another. The habit of growth of the cion is well shown in Fig. 177, illustrating the form and direction of the original branch, and the yearling grafts. It is evident, therefore, that a top-grafted tree is narrower and denser in top than was the tree originally, and that careful pruning is required to keep it sufficiently open. Each graft is virtually a new tree-top placed into the tree, and for this reason, if for no other, the common practice of grafting old trees close down in the large limbs is seen to be inadvisable.

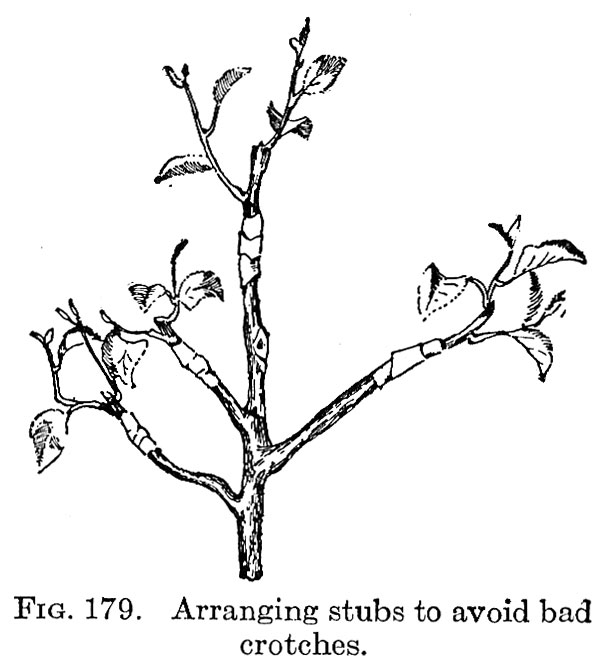

Small young trees with a central trunk or axis, such as have been planted only two or three years, may be cut off bodily, as at R in Fig. 178, only one graft being made. Usually such trees can be changed over in one or two years. When the young tree is well branched, however, it may be grafted in the branches as suggested in Fig. 179 (after Powell). In this case, care should be taken to choose alternating branches, so that crotches will not be formed.

Top-grafting is performed in spring. The best time is when the leaves are pushing out, or just before, as wounds heal quickly and cions are most likely to live. But when a large lot of grafting is on hand, it is necessary to begin a month, or even two, before the leaves start. On the other hand, the operation can be extended until a month or more after the leaves are full-grown, but such late cions make a short growth, which is likely to perish the following winter.

Professional grafters usually divide their men into three gangs — one to do the cutting of the stubs, one to set the cions and one to apply the wax. The cions are whittled before the grafter enters the tree. They are then usually moistened by dipping into a pail of water, and are carried in a high side-pocket in the jacket. The handiest mallet is a simple club or billy, a foot and a half long, hung over the wrist by a loose soft cord (Fig. 180). This is brought into the palm of the hand by a swinging motion of the forearm. This mallet is always in place, never drops from the tree, and is not in the way. The knife shown in Fig. 168 is commonly used. A downward stroke of the mallet drives the knife into the tree, and the return upward motion strikes the knife on the outer end and removes it. Another downward motion drives in the wedge. The sharpened nails and sticks commonly pictured as wedges in cleft-grafting are useless for any serious work. The various combined implements devised to facilitate cleft-grafting are usually impracticable in commercial work.

It is very important that the cleft-graft be kept constantly sealed up until all the wounded surfaces are completely covered with the healing tissue. Old wood never heals. Its power of growth is completed. If a limb of an apple tree a half inch or more in diameter is cut off, the heart or core of the wound will be found to be incapable of healing itself. It is covered over by the callus tissue that grows from the cambium underneath the bark. The wound becomes hermetically sealed by the new tissue. In the meantime, the wound should be protected by a dressing, a wax or paint, to prevent decay. In cleftgrafts, the surfaces should be covered with wax every year until they are closed over by the new tissue. In most cases the wax will loosen the first season, and sometimes it falls off.

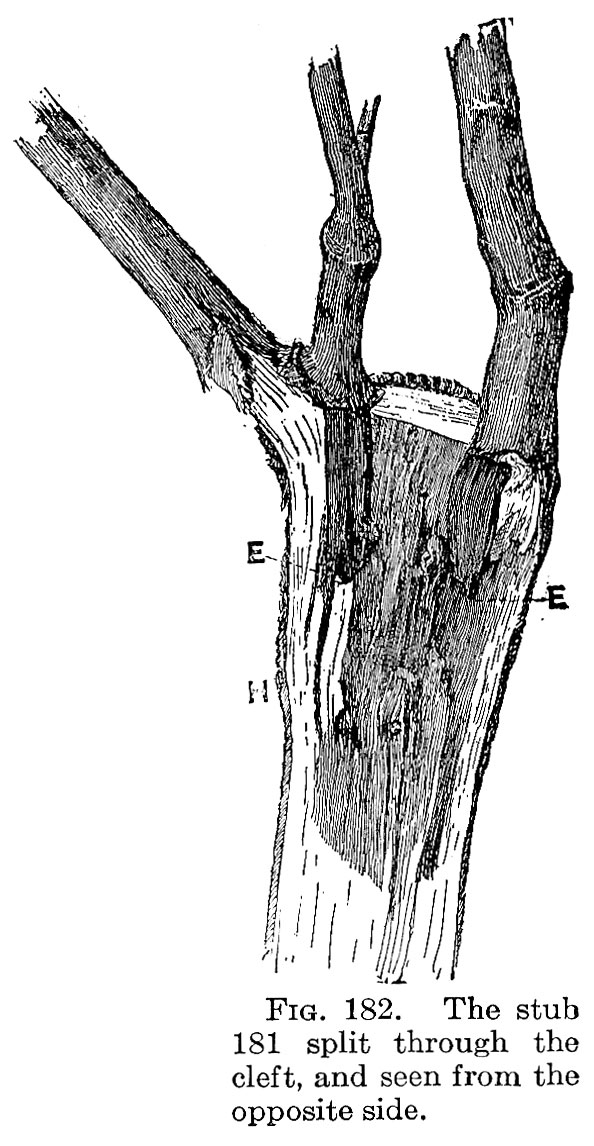

The character of the healing process is well depicted in Figs. 181, 182, 183. In Fig. 181 is shown a yearling cleft-graft of apple. The strip of wax along the side of the cleft is seen to have split with the enlargement of the branch, and the cleft has filled up with tissue and is now safe from infection of disease or rot. The roll of healing tissue on the end of the stub is seen about the border of the wound. This tissue has not yet covered the cleft across the end of the stub, and this cleft, if exposed to the weather, is a fertile place for the starting of decay, for the cleft does not unite except along the sides of the stub beneath the bark. When this stub is split lengthwise, following down the cleft, we may readily distinguish the location of the healing tissues, Fig. 182. The lower ends of the cions are at E, and they are now inactive and nearly lifeless bits of wood. The new or healing tissue has been built up on the outward side of the cions. On the left, this deposition of new tissue may be traced as far down as H, while it is thick and heavy at E and above. The whole interior part of the stub, represented by the dark shading, is dead tissue, which will soon begin to decay unless it is well protected from the weather. In time, the old stub becomes hermetically sealed by the reparative tissue. Fig. 183 shows a section of an apple graft nearly fifty years old. The original stub, about an inch in diameter, is still seen in the center, the end of it entirely free from the inclosing tissue. It is a dead piece of wood, a foreign body preserved in the heart of the tree. The depth of the old cleft or split is traced in the heavily shaded part of this central core. When this section was made, the cores of the old cions were still found in the cleft and the grafting-wax — faithfully laid on a half century ago — still adhered to the end of the stub, underneath the mass of tissue that had piled itself over the old wound.