The Milk & Human Kindness: My Winter Barn

The Milk & Human Kindness: My Winter Barn

by Suzanne Lupien of Thetford Center, VT

A description of my winter barn circa 2003, a look at British cheese types, the Cheshire cheese method, the cheese ladder, the curd mill, and the importance of sharing the cow chores.

My Winter Barn

What I’d really like to do, is to show you our barn, introduce you to the cows and let you experience first hand what I will be talking about today.

The best I can do is try to describe the scene this past Tuesday night: The cold true winter night, several feet of snow piled up around the old-style bank barn, stars bright in the sky, dog at my side, warm water and skim milk given to the pigs in their hut their warming bellies, as they bed down for the night in the straw. Stepping then into the upper barn, shuffle to the left on the wood floor until my foot finds the edge of the bale stack of our good, fine, green meadow hay and I carry a bale over the trap door and drop it down. The hay quality is high according to the real connoisseurs, the cows, who eat it with gusto. We are bringing back several fields in our village through good grazing practices and faithful trips with the old spreader, not by plowing and seeding and fertilizing with chemicals, but with many green cuttings given back to the field in the beginning, than later the cycles of composted manure and rotating the small herd around. Dozens and dozens of species thrive in this old-style mix, giving the variety of texture and aroma cows so appreciate. We made a couple of thousand bales of this glorious fodder and it fills one side of the hay mow, leaving a center aisle for a couple of old mowing machines and my new Grimm tedder, none of which made it into their winter places this year, thanks to the unexpectedly early snow. The other side of the hay mow is stocked with top of the line modern organic alfalfa hay and golden straw from a big farm in Windsor, VT, for which I am indeed exceedingly grateful, but I have to say that if I could put up 4,000 bales of meadow hay I know the cows would prefer it. Way up on the scaffolds is a stash of 3rd cut rich clover hay I happened to make, which I serve on special occasions like Thanksgiving and Christmas and when it’s especially stormy or cold. These two separate stacks of hay were festooned with bunch after bunch of carefully dried branches of maple, oak, beech, raspberry, and blackberry, which we harvested from the edges of our fields and which provide the cows with a great deal of amusement as well as minerals from the deep-rooted trees and bushes. These branches are fed out often and everyone loves them, pigs included. Even young calves set to work on them immediately. “How much stuff do you need?” people ask. I always say as much as you can get in. Cows are ruminants, roughage is their natural food. We feed our cows almost no grain: a cup of organic oats once or twice a week is all, and that only in the dead of winter. Concentrate feeding alters the cow’s system, vastly diminishing the milk quality and compromising the cow’s health. So that is why I work so dedicatedly to provide them with good hay. Basically, they can have all they want. And if there is the odd bale that does not meet their standards, well they lay on it instead.

I’ve got to get back to that bale I dropped down the hatch. So the pup and I exit the upper barn, go round the side down the path which leads to the milk room, the cheese-aging cave and the side entrance to the barn, a little two-plank door, which fits nice and tight, oh miracle, and squeaks on its hinges, and leads into the heifer stall, a good size area, 16’ x 12’, deep-bedded in clean golden straw, and housing, at the moment, Nora and Ivan, two Jersey calves born late October, early November. Now their thick furry flanks are beginning to show the dark colors of their mothers, who are themselves, mother and daughter. They are in top condition, perhaps a bit too well fed, although I’m not sure I agree with the accepted approach of keeping young stock as thin as deer and hungry. I’ve had some darned fat heifers and they’ve grown into fine milk cows with all the dairyness a farmer could hope for. I weaned these two calves two weeks ago, prefacing the actual weaning with a week-long public service announcement, repeated several times daily to all interested parties. And, miraculously, when the hard separating day came, it wasn’t so hard for anyone. A bit of mooing, but that was it.

I started to give the calves buckets of warm water right away, early mornings, and a basin of ground corn and kelp to take the edge off. Then hay, always the best hay for the heifers. Weaning can unleash a week-long moo fest, resulting in mother and calf becoming hoarse and edgy. Not this time. Four calves were born this fall and all respond to their names. All have learned to be hitched and halter-trained from 2 weeks old and have short lessons in these restraints most days 5 to 10 minutes, that’s all. Otherwise they are free. The dreadful sorrows of modern calf rearing: confined in tiny cages or hitched on a short rope to the wall forever are totally unknown to our calves. They are free to run and play and butt and dance, all of which they do every morning when I bed the big open area of the barn with fresh straw while their mothers are eating hay in their stanchions. The layout just happened to work perfectly. I put cows in their stanchions when it is daylight. They face out to the front open part of the barn, rear-end to the rock retaining wall side of the barn, and their manger is accessible to the calves from the open area, so they can still eat with their mothers, still be supervised and still get a good face wash too.

So I’ll get to that bale of hay in a minute. Just have to pass through the long hemlock gate which keeps these two calves in their stall, walk through the open cow lounge, still clean straw from this morning since I picked out most of the day’s cow flops twice today. The cows stay clean here. And by that I don’t mean that I groom fresh manure off them continually, if there is any; they simply find a wet spot to sit on rather infrequently. This keeps their skin clean and their fur is always fresh-smelling. When you bury your cold nose in their flanks at milking time, you’re always glad you did. So through the gate by the right side of the stanchion area, dirt floor raked clean, rock wall still white from the annual spring whitewash. The stanchion floor is wood; the stanchions are the old short wooden ones, made in Vermont a long time ago.

There are 6 stanchions: first Juliette, named for the great grandma of all modern herbalists, Juliette de Bairacli Levy, who knew herbal animal cures like no other. Juliette is a first cow heifer, quite a good size for a Jersey, gold and white, still not used to being milked now in her fifth week, so the adjustable clamp device still gets placed over her back every morning to keep her from kicking. But she’ll be alright in another month, I think. She has a nice bag, fairly long teats too, considering she is a product of modern Jersey genetics, which are good for the milking machine, but poor for the hand-milker. Number Two cow is Masha, our best milker, best disposition, glorious teats and not an ungraceful line on her entire being. Shiny black fur underside, rising up to a bronzy red over her back line. Picture perfect horns, too. Fabulous maternal instinct. Easy calving, deep capacious rumen, conscientious grazer. But now you would have noticed two things in this barn, a lovely sweet smell and the complete absence of tension. No jerking and shifting around in their stanchions, just calmness. Two key indicators of top quality milk. The sweet manure smell comes from the sweet hay diet, the calmness from good care and rhythmic, dependable feedings and milkings.

All the animals here were born on the farm with the exception of Nell, the next cow on the stanchion floor. She is Juliette’s mother. But when she arrived here five years ago, a cast-off from some dairy in Vermont, her starved body was a skeleton with a little bag under it. Apparently she had fallen down on the gutter cleaner, torn her cheeks, neck, back, and legs on the moving machinery and was left outside. She was still lactating when we got her, and I was able to make two camemberts a day from her production, and little by little she improved. The vet came and wondered why we bothered to save her and said her ovaries were so shriveled up that she’d never breed. The next time he saw her a year later he couldn’t believe it was the same cow: taller, brighter, fatter and with a lovely little heifer calf by her side. Nell is 10, so her frame is noticeably bonier than others, but her belly is full. Coming from a dairy farm she has had her horns removed, of course, so she can rub her head on my bottom, which is one of her favorite pastimes. Another is to lick the back of my hand and chew on it. She’s a peach, the most accepting and grateful one.

Beyond Nell are three empty stanchions. Lucy, daughter of Masha, is in Massachusetts, but will come back soon. Hazel is in the other big stall across from the heifer stall. She’s dry now and 7 months pregnant, and I’m keeping her apart because she will eat too much if she is in with the milkers and she already is fat owing to the fact that her dry period has been too long. Hazel is jet black, very sturdy for a Jersey, and has one horn that grows downwards, making her look like a telephone receptionist. She is a terrific milker, though, great teats, great butterfat.

The last Stanchion was Gabrielle’s. She was a beautiful black heifer from the same year as Juliette and Lucy. With a Canadienne father, she grew up to be wary and wild, which is hard to believe on this farm since the cows are handled so much. But Gabrielle was her own cow with a wild bit of white in her eye. She broke out of the fence everyday just for the heck of it, and resisted capture very craftily. So into the freezer she went. Bless her, she was delicious. As it turns out, you can’t always tell in advance how any cow will contribute to the farm. I thought Gabrielle would be a big milker; I’d breed her back to another Canadienne and hopefully get a bull to breed my other cows. But her contributions turned out to be her meat and her lovely black hide.

I divvy up the bale of hay, spreading it out in the manger the length of the stanchion area. I give some to the calves, the two in the stall, and the younger two resting in the open area, waiting for their mothers to come out of the stanchions and deliver them a bedtime snack. I’m filling the water tanks with a bucket from the faucet on the wall of the cheese room across the aisle from Juliette’s stanchion. Because this is an open barn it is cold in here, so hoses are more trouble than it’s worth. I favor daylight in the barn by day and have a hunch the daylight contributes to our unusually yellow winter butter. Compared to French cathedrals, our barn is rather more like Amiens than Chartres. Due to the extreme cold and wind this week I have stretched a sheet of plastic across the open door facing south and that has helped enormously. The cows haven’t been going out much anyhow, due to the deep snow and also the luxuriously large deep bedded area here in the barn. They have a lot of free area to roam and browse.

I milk by hand twice a day – the high point of the day really, when one can justify sitting and thinking (or not) for an hour at a time. There is electricity in the cheese room, but not in the barn where the cows are, so I tend to milk in daylight. Right now it’s at 7:30 and 4:30. I’ve noticed that the cows like to rest at daybreak and are invariably lying down – especially now in this cold spell – and I want them to get up, so I feed out a bale of hay at dawn, then come back a little later to start the day. The accepted industrialized model of “efficiency” certainly gets short shift on our farm, despite an excellent work ethic. I get a lot done and am at it all day, but it’s a flexible system, as in nature, not a regimented one, as in a factory. I spend time brushing the cows, scratching their backs and singing, and I play with the calves a lot too. They are the most wonderful creatures! Listening to the animals one can learn a good deal. For instance, they communicate in complete thoughts, not individual words. Clarity is natural for them. One cannot listen if one clings to literal, technically oriented ways of thinking and assessing. Cows do like singing, so I sing at milking. I fill the pail, carry it over to the little door to the cheese room, open it and pour the milk through the strainer into the can, then move onto the next cow. It is a lovely job.

These cows are not huge producers and that’s just fine by me and by them too, I might add. Their production is probably in line with the 1920’s standard. In the 40’s Newman Turner was warning that the health of the cows at that time was already beginning to be jeopardized because production was rising too far. We’ve never had any udder trouble on our farm; our cows’ udders are small enough that they can still run when they want to, which is very good for them, and our butterfat is very, very good. And because the hay is good and the barn is full of light, our winter butter is quite yellow. Our cows are giving 3 or 4 gallons a day each. This winter, as soon as the last 2 calves are weaned, I’ll be making a 45 lb. cheddar every 2 to 3 days. Makes an excellent grass-fed cheddar, Cheshire, Wensleydale and another old Dales cheese, which we revived and which now other cheese makers are making, called Swaledale. Gouda and a French farmhouse cheese are 2 low fat cheeses, which enable us to make a little butter. We also make yogurt. The emphasis is on quality rather quantity. My philosophy is that if you produce something that is exceedingly good, people will want it. So far this is what has happened here.

Someone said, “For a real bargain, while you are making a living, make a life.”

British Cheese Types

Throughout the British Isles there are many different cheeses, from Double Gloucester, to Darby, Caerphilly, Lancashire, and the king of cheese, Cheddar. Some of these cheeses are no longer made, no longer known even, except by a handful of elderly farmers who remember them. The constraints of modernization, the desire for a standardized product, and the use of mechanical cutting and packaging spelled doom and extinction for some of these extraordinary cheeses. Whose virtues won? Not the qualities the factories and the milk marketing board strove to eliminate. There is a great spectrum of variation among these traditional hard cheeses, some quite subtle, and at the same time they share broader similarities. The methods were pretty much the same, save for distinct cheeses such as stilton, and the subtleties come across almost like variations in personality or the differences in handwriting. Texture accounts for a lot in the character of a cheese and below I will list cheeses in two categories, the cheddar types, the long keeping cheeses with firm body and very close texture, then the Cheshire types with open, crumbly texture, higher acidity and shorter maturation and shorter keeping qualities. Generally speaking, these hard cheeses were all clothbound, relatively low moisture, and were aged in attics and backrooms of stone buildings with a moderate amount of ambient humidity. That’s because that is the character of that landscape.

Here is a basic listing of these two types:

| Cheddar Type | Cheshire Type |

| Leicester | Cheshire |

| Double Gloucester | Lancashire |

| Derby | Wensleydale |

| Dunlop | Caerphilly |

| Cheddar | Swaledale |

In the cheddar category, Double Gloucester would be the smoothest, most tightly textured cheese, owing to the method of multiple millings and pressings, and cheddar is likely to be the driest, and among the longest aged cheese, sometimes held for years. A cheese will lose moisture over time, a cheddar shedding 9% of its weight in the course of a year. Of the Cheshire types, Caerphilly is perhaps the crumbliest cheese, the others perhaps better characterized by their degree of flakiness. Such is the wide spectrum of both these cheese types. These variations have everything to do with timing, acidity, fat content, and curd size after milling. Remember what is often said, “The cheese is made in the vat.” I’m sure I’ve said this before to you. The rate of climb of temperature in the make process, and the strength of the starter have everything to do with the moisture, acidity, texture, flavor, and keeping qualities of the finished wheel. So it’s very instructive to look at different cheeses and their methods within a type in order to comprehend more fully the effect of the variation within a step such as the cutting and stacking of Wensleydale vs. Cheshire. To that end, I’ve chosen Cheshire as the cheese for this article, a gorgeous cheese in its own right and a close cousin of Wensleydale, the method of which I’ve included in a previous article (See SFJ Volume 37, Issue 1).

Cheshire

What you will need:

- 5 gal (40#) rich, fresh, clean milk

- 1 large pot, wider rather than taller, preferably. Sanitized

- An adequate and manageable heat source, cook stove, hot water bath, or other

- A perforated ladle, a curd knife, clean cheesecloth, and a sanitized lid for your cheese pot to hold in the heat.

- A bucket to catch the whey

- A dairy thermometer

- A good hoop (form) preferably stainless steel with a follower that matches the volume of milk

- A cheese press

- Coarse salt

- Kitchen measuring spoons

- Good (fresh or frozen) homemade cheese starter and rennet

- Your own cheese make sheet

- Scales, preferably hanging sort

**Referring to my previous articles on cheese making, sanitation and starter making would be most useful.**

- Heat milk to 86?F (keep the cream stirred in)

- Add 2-3% homemade starter, liquefied with sanitized spoon if starter is fresh. Ice cubed frozen starter, otherwise.

- Ripen 1-1 ½ hours (stirring every 10 minutes or so to keep cream stirred in. If it rises to the top when the milk is warmed you may lose quite a bit of it if you forget to stir)

- Add rennet 3.6 ml (.9 mil / 10# milk). Cover.

- Cutting after 95 minutes to ½“ cubes

- Rest 5 minutes

- Pre-stir (ever so gently!) 10 min.

- Cook to 93-94?F. Rate of climb 1?F every 4 minutes for 30 minutes.

- Cook for 30 minutes at 94?F

- Pitch 30-40 min. (“Pitch” means let curds settle, rest).

- Drain whey after curds have matted.

- Draw up curd in loaf-like form, in cheese cloth, snug.

- After 20 minutes, turn loaf over.

- After 20 more minutes weigh the curd mass with hanging scales, then unwrap, cut curd into 6” blocks. Keep curd blocks warm.

- Keeping curd blocks together, turn them over.

- After 15 minutes break blocks in half, by hand.

- With intervals of 15 minutes, break pieces again and again, making three breaks in all. Curd must be kept between 75-85?F.

- Watch closely for acid development, visible in firm knitted texture of curd, curd elasticity, sweet taste given way to squeakier texture and more acid flavor. Try the hot iron test.

- When the curd has arrived at these characteristics, mill and salt the curd 2-3 tsp. per # of curd. Curd size at milling – grape size. Curd can either be broken to this size, or cut with a sanitized knife.

- Mellow the curd for 15 minutes, covered with cheesecloth, again curd temperature kept in the range of upper seventies F.

- Hoop in clean, carefully lain moist (dipped in whey) cheesecloth in cheese hoop. Fold over your cheesecloth edges carefully, place follower on top.

- Press cheese the next day, moderate pressure for eight hours, then heavy pressure overnight. Heavy pressure will be at least 40 psi (look up the article on presses and pressing). (See SFJ Volume 36, Issue 2)

- Unwrap, re-bandage, flip cheese over and press again for one day.

- Unwrap, trim any feathered edges, cloth bind with lard (see SFJ Volume 36, Issue 4) Press for minimum eight hours.

- Unhoop, ripen at 50-60?F.

- Grade after four weeks.

- Best aged 9-12 months.

The Cheese Ladder

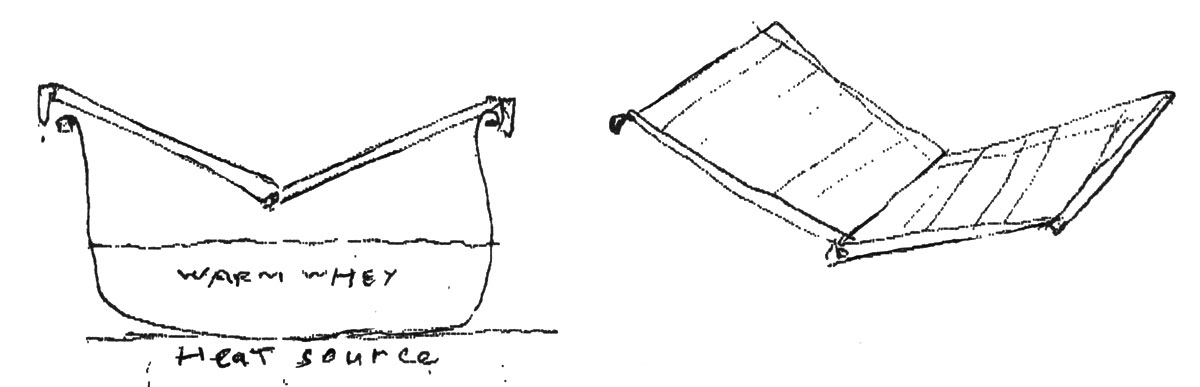

We are leading up to making that king of cheeses, English clothbound cheddar, perhaps in the spring issue and I want to tell you about cheese ladders which are very helpful in the home dairy in keeping curd warm. It is essential that your cut curd stays warm enough to acidify, and warm enough to press. If it is too cold, you will never get your acid development, nor will your cheese form into a smooth form in the press. Ambient temperature is important too and your kitchen-cum-cheese make room ought to be 70?F at the least.

Rigging up a cheese vat in the kitchen has its challenges, as you already knew. The cheese ladder can help. If you scoop out the curd ready for the first gathering step, using a sieve or perforated scoop, tying the curd up in the cloth, and you leave the whey in the vat, then you can keep that whey warm enough to act as a sort of hot water bath, and suspend the curd just over it on a “ladder.” Later on you can keep the salted, milled curd warm in the hoop the same way. It might look like this, and as always I recommend wood over metal, homemade over purchase:

A slatted “open book” like “ladder” with curls on the upper ends to catch on your cheese pot. The traditional ones were flat, but I like the “open book” shape: your curd can get closer to the warm whey.

A note about the typical “grade at fourteen days”

Although a fourteen day cheese is indeed very immature, quite a bit can be determined about a cheese’s prospects by taking a core sample at this time. Off flavors can be detected and those cheeses watched, or sometimes discarded. Correct saltiness noted, indicating how accurately you are salting, how well the curd has knit together, and how well the cheese binding is adhering to the cheese. I listen closely to my cheeses. I think they are alive.

Winter Exercise for You and Your Cow

On perfect sunny winter afternoons, why not rustle up a cow halter and take Bessie for a stroll? It’s good for her and good for the both of you to be together, listening to the chickadees, watching your footprints in the snow or the early spring mud. (Do avoid ice, of course.) I used to love to walk Nell to the village, tie her at the rail at the store and go and get a small box of fig Newton’s which I would share with her on the steps of the store, then back home. Seeing a cow out on a spree makes the cow smile and the passersby as well.

The Curd Mill

If you are making large wheels of cheese, say 40# or better, you might want to tinker with building your own old-fashioned curd mill instead of cutting up all that curd by hand.

A wooden hopper and a spinning drum with hardwood pegs and a crank handle, like an apple mill for cider-making. Hand crank mills of yesterday happily enlist the help of your four year old at milling time.

Sharing the Cow Chores

Sometimes, the cow chores end up being the domain of one person on the farm, husband or wife. As a choice or a necessity this is reasonable. But it is nevertheless essential that your partner do chores regularly, in order to spell you, to maintain a good friendship with the cow, and be able to replace you when you get the flu. Flexibility and mutual aid and skills are always a good thing and as there are different ways to effectively make a cup of tea or a loaf of bread, each committed and able farm partner ought to share the chores, the responsibilities, the joys and challenges of the dairy chores, even if one person appears to take on the dominant role. And, honestly, going down the line of cows, milking, then pausing to barf in the gutter, is not really that much fun!