Getting a Start

Getting a Start

by Paul Hunter of Seattle, WA

A couple years back from Vietnam, I’d moved on. Didn’t much like how my dad and granddad were running the Whittaker Ranch as a business. The old home place didn’t feel enough like a home any more. They had struck a deal with a big oil company that surveyed the ranch, laid out a grid, drilled and drained all 180,000 acres. Then the two of them mostly spent the money playing cowboys, turned it all into a dude ranch that advertised fun in the saddle, in big cities back east and on further west. But after a while it seemed like nobody much felt like playing cowboys with all that going on underground. Though we’d had good breeding stock, even the horses and cattle seemed to get a little too ornery and distracted by all the noises and smells.

I had saved most of my pay from the Army, and got a job driving schoolbus for the local school district from fall through spring, and helped out the family with the dude ranch in the summers. So I started looking for land, but it took a while to find any place worth a second look. I drove into the city to talk to the VA, then my local bank, and thought I could swing it with a healthy down payment. The cheapest places were all over-grazed and played out, gully-washed, full of jimson and tumbleweed. With the realtors it got so every place they showed me had a well full of mud, and a barn roof shot full of holes. Got so they teased me for tasting the water of every well that wasn’t bone-dry.

But then I found a place on my own, in the barber shop of all places. Wally the barber was completely bald, over sixty and had had a triple bypass, all of which I knew. What I didn’t know was that he was looking to cash in and move back to Missouri, which he called Missoura. While getting my usual hair cut, I happened to ask him what I asked everyone those days, if he knew of any land for sale. His scissors and comb quit their little clicking dance a minute, and in the mirror I caught his eyes rise up and stare at the ceiling of his little shop, like he’d just heard crickets up there somewhere, eatin’ a satchel of money. He was thinking of something, but had been cutting my hair a few years, since before I went in the Army, so I just waited him out. Eventually Wally lowered his gaze, studied me in the mirror, and said:

What kinda land would we be lookin’ at?

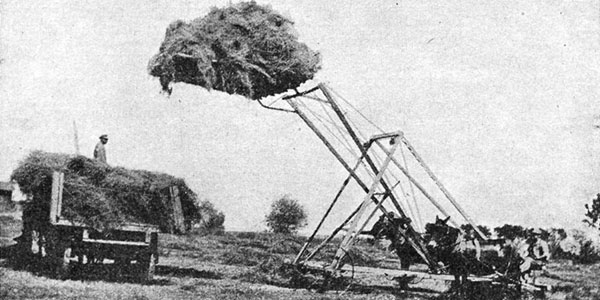

I want to do a little ranching and farming, raise some hay, oats, corn and the like to feed cows. Need some range land for grazing. And it would help if there’s water.

Does it have to be flat?

No reason.

I just said that because of what I been using it for.

And what is that?

A runway. Landing strip. I been building experimental ultralight planes.

You don’t say.

And I might be lookin’ to sell out.

How much land you got?

Twelve hundred acres.

You run any animals on it?

No, but they did before me. I don’t grow a thing on it. So it is just what it is.

And with that we were off to the races. Once he set his mind on something, Wally was a go-getter. We named a time to meet at the end of the day, to go have a look at his place. When I swung back around at six, the barber pole was turned off, the shades drawn, and he was at the curb, sitting on his bike. He waved at me to follow him out of town. It was a balmy spring day, and he was riding a Harley Duoglide, with a black helmet and matching leather jacket. I had never suspected. He knew me for a cowboy, with the hat and boots and all, but he also knew I’d been to war. And so had he. It was what shaped how we talked, and why we got along. The first haircut he gave me was fine, and I tipped him a buck and said I’d never ask where he learned to work a scissors. He’d been in the Navy in World War II, on a jeep carrier island-hopping in the Pacific. Said he’d gone in the Navy to get as far from Missoura as he could. When I said What’d you do, he said Aircraft mechanic, but mostly got in trouble with authority, and spent half of my tour in the brig. The day he’d told me that, he’d said, Look around this place. You ever wonder who runs a shop with one chair? A loner who has trouble with authority, who wants it all his own way—that’s who. Then he caught himself in the mirror and laughed, and I couldn’t help joining in.

Half an hour out in the country just before a crossroads we pulled in at a long gravel drive. He ran the bike straight into the barn and shut it off. I pulled to one side of the barnyard, turned around and parked my old pickup off in the weeds. As I got out he walked up, said he needed to talk to his wife a minute, then we’d look around.

His wife Annalee turned out to be a character all her own, jovial but serious as brass tacks. Not a thing got by her. She came along for the tour, straight back out the kitchen door behind Wally, wiping her hands on her apron, her long silver hair in a bun with a pair of chopsticks stuck through it. She was one of those who made sure she got in her half of the talkin’, so Wally wouldn’t miss explaining anything. In spite of his stories I could pretty much see how things stood. And they were both friendly and direct. There was no competition to pour my ear full, which I didn’t mind in the slightest.

The first surprise came in the old barn, which had a huge raised level floor and steel beams that spanned its forty foot width without posts. And on that floor were parked three small bright prop planes. Single-seaters — red, yellow, and blue. A look around told me all I needed to know. With his jigs and jacks, saws and clamps he really had built them right here. Did they all fly? You bet. He showed me the stickers and registrations, even unrolled a set of plans. I asked him Which one flew the best. Wally said Depends on your needs. The red one — the first one — is still fastest, but is a little squirrelly in much air. The yellow one has such a low stall speed you can hover forever, and is the cheapest to fly. But the blue one — the last one — does everything just about right, and is the one I’d practically take anywhere. A little more comfortable and roomy than the others. I built it back when I was thinking to maybe fly to Alaska. Land on the roads if I had to.

I climbed a ladder to the hayloft, which was roomy but empty. It looked like up here was where he had laid out the wings. Then we walked out into the open and had a look at the land. There was a crick that ran down through the place, and a fence around the outside that could use work, plus a few gates that were falling apart. I asked if the crick went dry in summer, and Wally said Not usually. He said they had a good well up by the house, that he’d been told was drilled to eight hundred foot, that never did go dry. It turned out his airstrip was the flattest land on the place, that had been planted in cotton when he first saw it, but had never grown anything since but weeds. He only kept it mowed so he could land and take off.

When they were done showing me around, I asked if I could see the house and taste the well water, which turned out to have no silt or bite to it, and no odor, that I reckoned the livestock would like. Then Annalee asked if I’d care to stay to dinner, which smelled pretty good — a baked chicken with vegetables, mashed potatoes and gravy. So we washed up and ate, and I thought of a thing or two more to ask, like whether either the barn or the house roof leaked. Wally said No, thank goodness — they’re both too steep for my taste.

While we ate Wally asked me about what I did in Vietnam. I told them I was what they called a “lurp,” went out on these Long-Range Patrols, a couple for ten days, hiding in an ambush we’d set up by the main trail coming down from the north. These were mostly country boys, not bothered much by the dark or wildlife. A dozen of us strung out in the weeds twenty feet off the trail in a big canoe shape with a light machinegun at the point of either end, and a few Claymore mines set out beyond the point to give us a heads-up when we had company. The North Vietnamese mostly just ran the trail in the dark, so we napped through the long days and in the night lay there wide-awake, set for action. On the fourth night of nothing I finally fell into a deep sleep, and dreamt I could hear horses pounding down the trail. My first dreaming thought was I’m the only one here who could catch a horse and ride bareback, They’re coming to take me out of here. But a few seconds later I sat up shaking my head, thinking Horses wouldn’t be here, they’re too good for this dangerous place.

Those runners never did trip a Claymore. A couple nights later they snuck up in the dark and practically overran us, came on so strong they drove us out of there. But that dream stuck with me for the rest of the tour, and sometimes still comes back. I finally realized it was how they ran barefoot, that on the trail sounded like wild horses, running without shoes.

I helped Annalee and Wally clean up after dinner, insisted, and that was pretty much it. Took a couple months to get the paperwork straight. They had bought the place for twenty-nine dollars an acre, and said they’d take thirty-six cash. I didn’t haggle for a minute, went straight to the bank and the VA, showed them I had two jobs and a healthy down-payment, and knew some tricks to raise cattle.

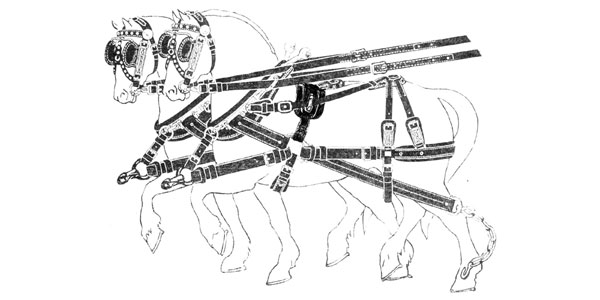

With the papers signed, I started to work on the fence every weekend, patching and setting out some new posts where the old ones had rotted. Once I had fixed up some new gates, I moved Hazel out to the place, along with half a dozen likely-looking heifers I’d bought on time from the family, and while I was at it bred them to their best bull. Took till the second year to fatten their calves and pay off.

Wally and Annalee moved into town once they’d sold off the three little planes. They had a little more trouble selling the one-chair barbershop but finally did. Meanwhile Wally quit charging me for haircuts until they left town the following spring on the Harley, towing a little two-wheeled trailer, headed back to Missoura, far from the ocean, where he was gonna see if he belonged.