What the Mail Must Go Through

What the Mail Must Go Through

by Paul Hunter of Seattle, WA

Hardly a soul on my mail route knew I was even a horseman till they saw Ketchum’s tracks that morning breasting thirty-some inches of snow. I hadn’t even known what I was going to do about that much snow when the sun rose on a cloudless dazzling sky, where the valley lay stiff and still. The postal jeep had about sixteen inches of road clearance, and even heading downhill in four-wheel drive had been stopped in a couple car-lengths by its undercarriage packed tight with the white stuff. I’d had to shovel out the worst of it, then saddle and bridle Ketchum anyhow, get a loop on the rear bumper and tow the jeep back into my barn where the town let me park it. The town didn’t own a real shed but the one behind Town Hall where they parked the school bus and snowplow. I’d given Ketchum a couple flakes of hay and broke the ice on his trough then called Hank Overton to find out there’d be no snowplow this morning.

This was the first time in my two and a half years that I’d delivered the mail horseback, though the notion had crossed my mind, usually on days of balmy weather – it flickered like an old silent movie just as sleep dropped me into some dark ditch that seemed to suit the time of year. This was the first big storm like the old-timers liked to brag about, that would bottle up the valley on both ends, sometimes for weeks or more. Today the roads went unplowed since Hank Overton was down with the flu, weak as kittens without mama, and by way of replacements there was not a soul. To be honest I’d been told there hadn’t been any since Hank had got the plowing job, for going on thirty years. Things being what they are hereabouts in Melinda, Montana, winter population at the moment 499, only one snowplow driver at a time was trusted with the keys – that way everybody knew who was responsible, the truck got lubed, the oil changed, the blade adjusted, and things rarely if ever broke down. Hank had only been sick a couple times for a snow day or two since he’d got the job at 23, after a stint driving an Army tank during the first Gulf War. And through winters in the valley he sat tall, since he was known to everyone, skilled and dependable. Winters the snowplow was a lifesaver, and practically his life.

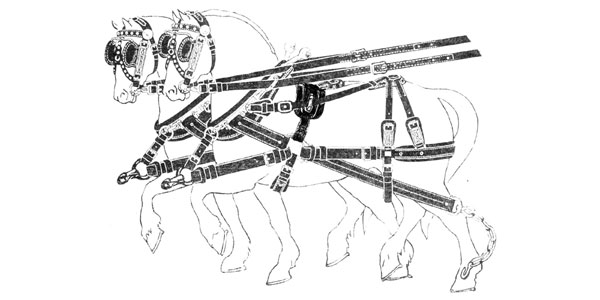

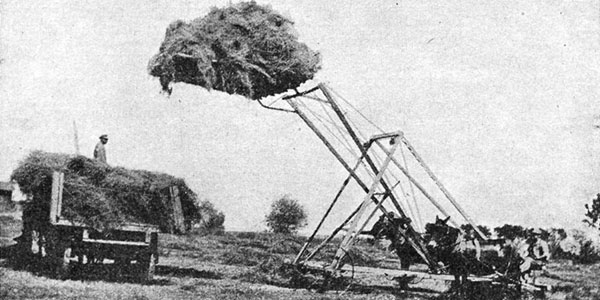

As for the mail, that first morning I got a pair of mailbags from the storeroom and clipped them together to make some oversized saddlebags. But they still wouldn’t carry the full day at once, so I figured to cut the route in two. Then Ketchum and I did the delivery in a little more than double my usual time in the jeep, as more than a few folks stopped me to jaw about the novelty of having a cow horse on the streets of town in mid-January, where with the school bus parked behind the snowplow the kids were enjoying a rare day off school. I got to wave at a few other riders that morning, come to town from the ranch for necessities, or just to tie up on the main drag and go into Cosmo’s for the flapjacks and eggs Breakfast Platter. I got to quote the unofficial Post Office motto more than a dozen times for admiring patrons, and talk about those Persian mounted couriers praised by the Greek historian Herodotus in 440 BC. I’d pull off my big pale Stetson and read from the scrap of paper I’d tucked in the sweat band. “Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” When I explained how these couriers were stationed with their horses along the royal road a day’s ride apart, Mayor Pembroke on the front steps of City Hall said Not bad for a college boy whose history degree never quite poured him the gravy. I just smiled and didn’t take offense. I still knew how to sit a horse and had learned my mail route all at once my first day, and the jeep even in four-wheel drive would have gotten no traction except for a few windswept high spots on the roadway, balanced by drifts deepening along some mailbox clusters till they reached four feet and soaked my boots in the stirrups, before I thought to step down and scrub my belt buckle stuffing mail in those little tin burrows.

This first time I got lucky. The weather stayed sunny for two days, which let Ketchum follow his own tracks and made the second day a breeze compared to the first. But then overnight we got another four inches that let us make more tracks. Then it brightened up again, though it still stayed well below freezing. Turned out there was one bad spot, on the road to the east outside town. I urged Ketchum up from the row of mailboxes, and he took a couple steps, then slipped and sagged to his knees. Under the light cover of fresh snow was ice in rough humps and slick patches. This must have been where the sun laid its hand yesterday, burned through to the blacktop awhile. I jumped down and helped him rise, then led him up onto the road, stood and talked to him a little while I checked him over and rubbed his legs. But there he stood huffing and steaming in the frosty air, a little indignant. The only damage seemed to be to his pride. Ketchum’s a good horse, and once he’d regained his footing he didn’t slip anywhere else, though I did watch him steer clear of fresh snow over ice, when there was a choice in the matter.

I rode the route on Ketchum six days in a row before Hank felt up to starting the plow, and carving his own route through town. As a bonus Hank also plowed the three biggest parking lots – by Citizens First Bank, Dunlop’s Hardware and the Western Family Market – while they still stood empty in the rosy dawn. My first day saddlebagging the route had been hardest, breaking trail through some sizeable drifts. Sometimes I could just lean over to reach a row of mailboxes, but sometimes I’d have to step down into a drift to get the mail in. Once I sunk in practically to my armpits. But after that first day I mostly gave the horse his head, since Ketchum was a quick learner. After a few days everybody had got used to the change and most liked it. We weren’t charging by the hour to deliver mail anyhow, since it was a regular route that said not a word about conditions, only detailed the size of the name on each mailbox, and which side of the road they’d be on.

By the time I was back in the jeep there were even townspeople talking about putting up a hitching rail for Ketchum out behind the post office, that Hank had plowed extra-good. He’d somehow got word that I’d had to tie my horse to a light pole to go in the PO to sort and pack my saddlebags for the day’s deliveries. I’d kept delivering the mail in deep snow because my young horse didn’t seem to mind doing it. It wasn’t like pushing all day up a frozen mountain. The floor of Medicine Valley was mostly flat, with some rolling foothills to the route at either end, that needed a push here and there, that Ketchum seemed more than up to. Turned out he mighta been a little stir-crazy and barn-bound himself, so liked the excuse to get out and push through the snow to get the job done, long as we didn’t overdo it. Not that I told anybody. I kept my mouth shut and reaped the benefits, which meant being seen as kind of a young latter-day old-timer who’d found a way to keep on keeping on. It was really a coincidence, the treat of having a good horse to work, but my neighbors liked the look of it, and so did I. After all, I’d bought what was left of the old Craig place, the barn and sheds and house all painted red on a twelve-acre plot, and had brought my young horse off the folks’ old place in Wyoming to go exploring on my days off, maybe to recall my ranchin’ ways, and here I was maybe even get paid for it.

Of course it didn’t hurt that on the third day the local shopping news ran a big picture of Ketchum thigh-deep in snow, rider bent down over the horse to stuff a mailbox, with a nice little write-up by someone named Bonnie Seasongood, about how the spirit of the Old West was alive and well this winter, not even hibernating. The snow was still flying a little that third morning when I went into Cosmo’s for breakfast, so I’d tied Ketchum to a power pole out front, and covered him with my slicker. They’d just delivered a bundle of newspapers to the cafe, and when I stepped in the door, folks started clapping, till they remembered their manners and quit. In short order I was introduced to Bonnie Seasongood herself, an energetic young woman with an arresting stare, who I’da thought wouldn’t know I was alive, though I knew her and her family for sure from my insider role in the U.S. Postal Service. Every address came with the names of who lived there, and there weren’t all that many. So when she stuck out her hand I said Howdy, you must be Box 134 Hopewell Road, and she looked at me like I’d just pulled a rabbit out of my Stetson, though the Hopewells had been her grandparents on her mother’s side.

It felt like I went from being the most anonymous cowhand alive to being halfway famous. And while sharing a platter of biscuits and gravy, then a Denver Omelet and half a gallon of coffee Bonnie Seasongood seemed to have taken a liking to me. She hadn’t really set out to be a reporter for The Medicine Valley Forager. She said she was just taking what she could get while she waited for a teaching job to open up at the Melinda Elementary School. When I asked her which grade she was lookin’ to teach, she steadied her gaze and said Guess.

I studied this lady with the dark braid down her back, a liquid pool to her green eyes and her mouth in an impish twist, and wondered was I lettin’ myself in for some heartache. Then on impulse I said I bet you want whichever age is the most troublesome with big changes up ahead. Sixth grade would be my guess. But if we were talkin’ high school, I woulda said ninth. Her wide smile made me blush so bad I said I had to go check on my horse a minute.

I’d been too tired after the first couple days pushin’ through snow, but that third night I walked the half a mile to the bar in town, after I’d fed up Ketchum and myself. I usually went in once or twice a week, more in winter, less in summer. The place was called the North 40, and was the one year-round bar in the valley. Sometimes I just went in to chalk my name up for a game of pool or darts and a beer or iced tea. On Friday and Saturday nights they had food, served outsized buffalo burgers with coleslaw and bodacious home fries. The place was different in summer than in winter. Summer people sat in little knots of two to four, amused themselves and ignored whatever else was going on. But as winter came on, folks gathered at the big picnic tables, huddled together and commiserated with strangers – who mostly didn’t stay strangers for long.

When I walked into the North 40 that third night the chatter dried up, as folks swiveled to give me the eye. The North 40 was the newest business in Melinda, and I’d been told the couple that owned it had been here 30 years, enough to pay off that 40 acres they had just out of town beyond my place, where they raised their buffalo. There had been a bar in the building before, but the old man who’d owned and run what he’d called The High Lonesome had died in his sleep one balmy afternoon and left no kin. The town’s summer population got as high as 1200, because of the draw of mountains to the north, for fishing, hiking, back-country pack trips and the like, and summer homes in the valley for those who could afford to dream of being two places at once. In the winter the population dropped down to 500, and some years might drop below 300 right after Christmas when anyone who could wangle or afford it headed south. Winters here could be brutal and everlasting, and meant extra work in hard conditions not just for ranchers and farmers but whatever else folks did for a living hereabouts. Melinda wasn’t perfect, but most of us here liked it about like it was. The valley was an eyeful and had a wide-open feel year-round, with a nice trout stream running through it, with more than enough to see and do for any decent soul. And there were no famous attractions to crowd out the anonymous and quiet-living rest of us.

The bar’s interior walls and ceiling were peeled log half-rounds, with several truly grand stuffed moose and elk and buffalo heads, trophies hung higher than they woulda stood on any living beast, though the building on the outside was brick with stone stoops and window sills. In the daytime the place was dark, and with those huge horned heads staring down at us with their amber eyes someone had thought to light up, so they made the place feel like an animal den. At night it was actually brighter, with three huge wagon-wheel chandeliers eight feet across hung over the three picnic tables, and stage lights over a little bandstand in what had been a dark corner for when there was music and dancing.

The topic around one picnic table that night was how Hank Overton’s illness had reacquainted folks in the valley with the miseries of shoveling their own snow any way they could. Some had a garden tractor or riding lawnmower with a plow to get after it, and some had a snow blower that wasn’t half-bad when the snow was a matter of inches. A few had a plow to clip onto the big ranch truck so they could at least run out to the main road and check the mail in the box. But I was surprised how many folks in town shoveled off their porches with a rusty coal shovel or grain scoop. A few spanked their front steps with a broom, and otherwise waited for it to melt off or blow away.

That evening I had a grand old time, jawing with the winter people. They all knew each other, though strange to say more than a few of ’em still didn’t know my name. But I already knew most of their names and box numbers, and was glad to shake hands and introduce myself. Turned out Ketchum was the real ice-breaker, at the moment the best-known and admired horse in the valley. I did meet a couple of attractive young ladies who seemed interested and unattached. I kept wondering where they’d been last winter – until I remembered there hadn’t been much snow, and what there was had been quickly plowed.

That day and thereafter I got a thumbs-up wherever I went, once they heard we were standing in for a postal jeep that couldn’t handle much by way of drifts. And after the sixth day, when Hank Overton was back on the plow, the postmaster Elton Waverly called me in to talk about the horseback delivery business. As my boss he praised my initiative, then said he’d been talking to the mayor and some other town elders, and they all wondered if I’d be up for doing the mail aboard Ketchum, rain or shine, mostly shine, with my cowboy hat on. We talked over the difference in time it took, and the cost of winter hay and grain versus the high cost of gas in the valley. The postmaster liked the numbers I gave him, called it a win-win and seemed cheered by the whole idea. And I said as long as the horse didn’t balk we could just go right along. So we dickered a little, and came to an understanding, that I’d ride the horse every other day, three days a week, so as not to wear him down, and use Ketchum as backup when the weather got rough, and split the winter feed bill down the middle. The last thing he said was how the town elders knew better than ask me to change the name of my horse, but hoped I wouldn’t be out peddling the charms of Idaho. I laughed and said the name was a cowboy joke off my folks’ place in Wyoming – about how some sorry cowhands who can’t ketch ’em might never get a ride.