Ask A Teamster: Driving

Ask A Teamster: Driving

by Dr. Doug Hammill D.V.M. of Montana

Dear Doc,

I’m having some problems with a pony and I wonder if you can help me out. I’ve just taught him to drive, and for the most part he’s doing pretty well, but I can’t quite get him to relax. The first time I hitched him we went around the arena a number of times, but his head was in the air the whole time and he just never quite settled in. He seemed really tense. So I ground drove him some more over the next few days and then tried again. Same problem — he just seemed very nervous about pulling the cart. He has seen the cart a lot and we have pulled it behind him so he could hear what it sounded like. I think I’ve done all of the ground work to get him ready, it’s just when he’s hitched that it seems like it’s not coming together for him.

I don’t want to take him out of the arena until he seems more relaxed. I’ve been driving for a few years, but this is the first horse I’ve started on my own. Should I just keep driving him to give him the time to settle in and figure it out? I checked the harness fit and I don’t think that’s what’s bothering him. I’m just not sure what I’m doing wrong, and I’d hate to ruin him. He’s a 7-year-old Haflinger. He was broke to ride when I bought him and has been handled a lot.

The reason I am so worried is that I was at a recent driving club event where there were not one, but FOUR wrecks. At least two of them were runaways. Thank heavens nobody was badly hurt, but from what I saw, it was just pure luck that a horse or driver wasn’t severely injured. I know a number of trucks were smashed into and there was a lot of property damage.

Thanks for any advice you can share. Jane

Dear Jane,

I commend you for recognizing your horse’s concern and discomfort with the process of being hitched for the first time — and for quickly taking the action of retreating back to more ground driving before a mishap occurred. That head-up-in-the-flight-position and tenseness you observed are classic danger signs that people often ignore and continue in spite of, or miss the significance of altogether. Many times drivers keep such a horse going in hopes he will eventually settle down and accept the new task — but in my opinion that is taking unnecessary risks and does not give a horse the consideration he deserves. Some horses are able to hold themselves together and eventually come to accept whatever the uncomfortable challenge may be — but they may take a long time to become truly comfortable with it. Unfortunately, more than I care to mention sooner or later reach a point where their fright-flight survival instinct reaches critical mass and they run off or blow up — as was tragically demonstrated at your recent driving event.

Going back to ground driving without the cart was exactly the right thing for you to do. When a horse becomes concerned, confused, anxious, upset, fearful, etc., we should simply stop whatever we are doing, take a time out to calm him down, and proceed by doing something we know he can accept and be comfortable at. I call this “going back to kindergarten.” The sooner and more often we do it the greater the chances of preventing a mishap. Using this technique and thereby returning the horse to comfort will tremendously increase the odds that a horse will become accepting and settle down in spite of what he found fearful. Better to eliminate the fearful object/action, defuse the fright-flight reaction, work at something he can comfortably handle, and prevent a potential wreck. Responding this way each time with consistency will eventually convince the horse that he can depend on you to take care of him and keep him safe whenever something concerns or frightens him.

“Going back to kindergarten” allows the horse to relax and turns a problem into a success. There will always be an appropriate time later to work back up to whatever it was that was too much for the horse to deal with. And, if we can skillfully work back up to the original goal (hitching to the cart in this case) in small enough, bite sized, “baby steps” (over time and with repetition), then the horse will not be apt to become concerned with any of the steps along the way — including the original task he had difficulty with. But if he still can’t handle it, more repetition of “back to kindergarten” and “baby steps” will eventually take care of it. Keeping our horses feeling safe and comfortable at all times is one of the greatest ways we can prevent behavior problems, runaways and wrecks — as well as improve performance in general. Over 100 years ago Jesse Beery, an extraordinary horse trainer from the 1800s wrote: “Colts or unbroken horses are especially susceptible to fear. Almost every step in their management . . . lies in overcoming resistance excited by fear.”

You recognized the head up and tension as danger signals — communication from your horse that what he was doing did not feel safe to him. It is critically important that we humans learn the body language of horses and constantly observe, interpret, and react appropriately to what they are “telling us” or “asking of us.” If we don’t respond to them when they “speak” by helping them regain their comfort and feel safe, as a good herd leader would, then they may quickly reach a point where they decide to take matters into their own hands to survive. Using harshness, force, and/or causing pain (yelling, bit, whip, etc.) at times like this will do more to confirm their fear and trigger the flight response than to solve the problem. Legendary 19th century horse tamer John S. Rarey left us with these words of wisdom: “Almost every wrong act of a horse is caused by fear, excitement, or mismanagement. One harsh word will increase the pulse of a nervous horse ten beats per minute.”

The fact that going back to ground driving for a few days was not successful in alleviating your horse’s concern about being hitched to the cart gives us some very important information and also raises some questions:

First, your horse is telling you loudly and clearly, “I can handle ground driving but that noisy contraption with the sticks along my sides and the wheels scares me.” In other words, he is not adequately desensitized to certain aspects of the sights and/or sounds and/or feel of the cart. To quote Jessie Beery again: “His fear is governed by his sense of touch, sight and hearing; and it is through these senses we obtain a mastery and at the same time remove his fears … each one of these senses must be educated before the colt is [considered] trained.”

Second, it poses the question as to whether there may be some other weakness or omission in his training before you first started ground driving that needs to be dealt with. Look over my list of “Tests a Horse Must Pass Repeatedly Before Ground Driving,” (see box) and test him out to see if he can pass them all — on several different days and in different locations. If he passes you can proceed with ground driving. If not, work on the things on the list until he can willingly and comfortably do all of them in a very solid way, in several locations time after time.

The importance of ground work with horses cannot be overemphasized, but sadly it is perhaps the most overlooked and neglected aspect of training. Fully 90% of the training I do with horses is accomplished on the ground, and much of it is done informally as I go about my normal daily activities with the horses, rather than in formal training sessions. I am constantly teaching and testing the things on the “Tests a Horse Must Pass…” list.

Third, consider whether there is anything different about you and/or what you are doing when you hitch him to the cart and drive that may be contributing to or causing his concern. Horses effectively mirror our attitudes, emotions, actions, reactions and behavior. Perhaps he is picking up some concern, doubt, fear, tension, etc. from you. We commonly transmit concern to our horses by such unconscious, subtle things as a little extra tension on the lines, a change in our voice, abnormal breathing or holding our breath (yes they can tell).

If we are anxious, concerned, uncomfortable, impatient, worried, fearful, in a hurry, etc. our horses will pick up on it and become so as well.

Finally, there are other miscellaneous factors that may be causing or contributing to your horse’s behavior in some way. Obscure things like fit and comfort of the harness, wolf teeth causing irritation or discomfort with the bit, uncomfortable or severe bit, heavy shaft or tongue weights, and endless other possibilities. Whether or not such things bother a horse when ground driving, it seems they can be magnified when the horse is hitched and/or pulling a load. We should constantly be looking for and correcting these more obscure causes of discomfort.

Take It Slow

Never hesitate to return to more basic and comfortable tasks for the slightest reason — that is, BEFORE the horse gets anxious, confused, concerned or bored. Be sure to mix in lots of time out for processing and relaxing, as well as an abundance of kind words, and gentle caressing.

We humans are impatient. We think horses should be able to reason, understand, learn and accept things just as we do. But they perceive, understand, communicate, think and react very differently than humans. Unless and until they feel safe and comfortable, nothing else really matters much to them. According to horsemanship clinician Mark Rashid: “When it comes right down to it — I think it’s just like the old man said — there’s something about horses that we all need to understand: Their only real job in this world is to stay alive from one day to the next. Nothing else really matters.”

Although we think we go slowly enough for horses, break tasks down into small enough steps, repeat things enough, are gentle and patient and persistent enough, they are often telling us with their subtle body language that we are not — and unfortunately we often miss or ignore their pleas. And of course, their emotions, abilities and needs can vary from one moment or one day to the next — and according to their different personalities and personal histories as well.

For the sake of discussion let’s assume that your Haflinger can repeatedly pass all the pre-ground-work “tests.” And, when you are ground driving him, be sure he is willing, comfortable and relaxed. He should also be proficient at starting, stopping, standing patiently, backing and turning both directions when asked.

If not, you probably (hopefully) would not have progressed to hitching to the cart in the first place. Any horse that cannot consistently meet these requirements should continue to be schooled at the level of ground work and ground driving before he is asked to pull, or be hitched to, anything. By anything, I mean not even dragging a single tree on the ground behind him.

However, once a horse has repeatedly proven himself at ground driving and is judged ready to begin pulling things, as your horse seems to be, I recommend (as always) a gradual progression using small baby steps. From your question I’m unclear whether you taught him to drag things on the ground before hitching to the cart.

Break It Down

I am certain that hitching to the cart is too great a challenge for your horse without some lessons, or more lessons, on pulling other things — to transition more gradually toward the cart. My normal progression is to start with pulling just a single tree; then the single tree with a chain dragging behind (seems like an unnecessarily small baby step to a human doesn’t it?). Next, I add a small pole or two or a very light stone boat, and then begin gradually increasing size or number of the poles or weight on a stone boat. I do not ask a horse to pull the false shafts or cart until I have him pulling these things flawlessly — first a small pen, then in a larger pen or small arena, and finally out in increasingly larger and more open areas. If at any point the horse shows concern that cannot be defused with a time out, comforting words and gentle caressing, we go back to something more basic in one of the smaller, safer feeling enclosures. Ultimately, I will actually put them to work around the place skidding poles and small logs, pulling things on the stone boat, or dragging a harrow to season them well before hitching to false shafts in preparation for a wheeled vehicle.

Rather than go directly from dragging things on the ground to hitching to a cart, I prefer to create another baby step by hitching to what I call “false shafts.” I always habituate a horse to pulling false shafts before I hitch him to a cart. By doing so, he can get comfortable working between the confines of the two shafts without the weight, noise, complexity, etc. of a cart — not to mention the potential risk to an expensive vehicle. False shafts simply consist of two poles connected at the rear by a crosspiece, and some hardware to hook the traces and hold back straps to. You can find information for constructing false shafts for various sized horses and ponies on my website. (By the way, when you do hitch a horse to a wheeled vehicle, I recommend using a cart at first because a four-wheeled vehicle can jackknife.)

When It’s Time To Drive

So much depends on how we have our driving horses start, and how well they stop and stand for us. Teaching ourselves and our horses how to execute nice, smooth, comfortable starts sets the mood for whatever we do once we are in motion. When we ask a horse to make his first drive, we have a critically important opportunity to help him start out in a comfort- able, relaxed, safe way.

The best and most specific method I’ve seen for accomplishing this is a technique I learned from Steve Wood, a great horseman, teamster, driving instructor, and trainer of driving horses from Minnesota. Steve and I have conducted some workshops and a recent seminar together, and have learned some valuable things from one another. I highly recommend the use of Steve’s one-step, three-step, five-step method (below) when teaching any horse to drive. I feel it will be particularly beneficial for your horse, Jane.

Here is an article by Steve that describes this method:

YOUR FIRST DRIVE SHOULD BE ONE STEP LONG: THE ONE-STEP, THREE-STEP, FIVE-STEP METHOD

by Steve Wood, Wild Wood Sleigh and Carriage, www.wildwoodsleighandcarriage.com

How I Learned About This Method

The first drive for any horse is tremendously important to their future as a successful driving horse. We need the horse to trust us, so we are responsible to do all we can to make that first drive as comfortable as possible. Let me go back several decades and give you some background on how I came to utilize the method we use for our first drive.

When I was young and Dad was getting ready to drive a team of horses, I would finish hooking the last tug to its single tree hook, and Dad would climb aboard the vehicle. I’d hear him say, “I’ll just step them up a couple steps and straighten them out.” No matter what the vehicle — buggy, spreader, stone boat, sleigh, or plow — or the number of horses — two, three or four — that was how we always started out: “Just a couple steps.”

I knew Dad to be a great teamster, but this routine seemed a bit silly to me. It took years of watching this to see what was really going on. During that “couple steps” the horses stepped off in different directions for about one step and then all came together in the next one or two steps. At this point Dad would stop the team, he would pronounce it good to go, and I would climb aboard. As we would drive off, the horses would jostle around again on that first step and then quickly settle into the pace Dad was setting with that magical touch on the lines.

As the years went by, Dad moved to town, and he began coming out to my farm “to help me get the colts working.” We worked several young horses each Saturday and Sunday. We settled into a routine that sometimes had us working three or four young driving horses in a day.

Pretty soon I developed a specific routine for that first drive and, by golly, the young horses are much more comfortable in their work. We have found this new routine to be indispensable to the outcome of the young horse’s future as a driving horse.

We call it the “one- three- five-step” method. The name reflects just what we do; we take one step and stop, then three steps and stop, then five steps and stop. Each time we stop, we read the horse’s body language to understand how he feels about this new job of pulling a vehicle around. We watch all the body language, but in particular we watch the head position to help us decide how he is feeling. Before you and your horse take that first drive, you need to be sure you’ve done the preparation work and have the right equipment.

Before That All-Important First Step

Our training begins by doing a thorough job of ground work, starting with teaching the horse to stand in one place for at least three minutes with just a halter and lead rope.

Finishing the ground work involves many repetitions of the horse successfully starting, stopping, and turning while wearing the full harness and bridle with the driver and helpers walking on the ground giving commands by voice and by line contact.

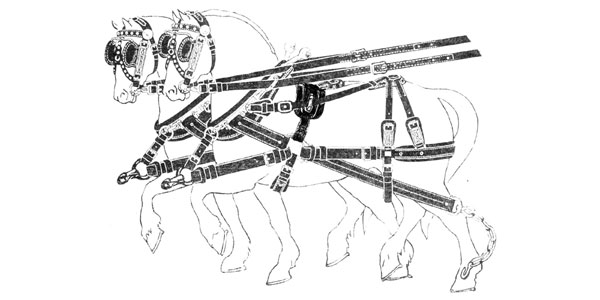

A word of caution about the harness you use. The harness that your horse is wearing needs to be good solid construction, fitted to your horse for his comfort. Beware of using harness that may have hung in Grandpa’s barn for many years and then been soaked in oil to look like it’s ready to go to work.

What Vehicle Should Be Used For The First Drive?

The first vehicle any horse should pull is a small stone boat. If we had all hooked our new driving horses to a stone boat for their first drive, I feel there would be many more antique vehicles left for our well-trained driving horses to pull around.

The stone boat is not meant to be a heavy load that the horse cannot run away with. Instead, the stone boat is a vehicle that the horse can pull comfortably, yet will not roll forward and tighten the horse’s breeching when the horse comes to a stop.

At this early time in the driving horse’s career, we shouldn’t ask the young horse to accept pressure on the breeching when they are already worried about the pressure on their collar from the stone boat. If we do ask the horse to stop, and a rolling vehicle tightens the breeching, most horses will feel claustrophobic because they cannot find a way to relieve the pressure. That feeling of claustrophobia will cause many new driving horses to let their flight response take over. So a stone boat it is!

How To Get Started

You should always use a helper — someone the horse knows and trusts — when you first start a horse. The helper holds the horse with a halter under the bridle and a lead rope attached to the halter. The helper stays in front of the blinders where the horse can see him. The driver hooks the tugs to the single tree while holding the driving lines in his hands at all times.

For this system, “one step” refers to the horse moving all four of his feet forward once. Look at it this way: when the horse moves his first front foot forward he has begun his first step. When he moves the opposite front foot forward he has completed his first step. That is when we command the horse to stop.

After all is ready, the driver commands the horse to take that step and then commands him to stop after one step. When the horse is stopped, the helper reads the horse’s eye for alarm signals while the driver checks the tail and back muscles for tension that would show discomfort. Both the helper and the driver are looking at the all-important head position of the horse.

If the horse is holding his head raised into the up position, he is showing you he really doesn’t like the new sensation of the pressure from the collar. Nearly all horses, however, will relax and drop their head to a normal position after a few seconds. That shows us they are relaxed and relieved to have the pressure removed from their shoulders. Give the horse as much time as he needs to show us he is relaxed and ready to pull again. (Compare the two head positions in the photos.)

In this photo, you will see a relaxed head position. Note the calm eye and the relaxed tail position.

What Is A Relaxed Head Position?

Your horse will show you his relaxed horse head position while leading him with halter and lead rope. All horses have a different relaxed position. We see similarities within breeds for the relaxed position, yet even full siblings will have a different relaxed position. So get to know the horse you’re driving by working with him a lot doing the ground work and long lining (ground driving) before the first drive.

Every horse that I have worked with will have a raised head position to show worry. In the light horse breeds, the difference between the relaxed head and the raised head is about 4 to 6 inches. In the draft breeds, the difference is much more subtle. The difference for the draft breeds is about 2 inches. In my experience, the draft breeds are much more subtle in all their body language. So you will need to get used to the horse you are going to be driving and learn his language. He speaks it every day, even when he has no harness on.

Important: If the horse does not show you the relaxed head position in a few seconds, take this as a sign that you and the horse need to spend more time on ground work. Unhook the stone boat and proceed with ground driving that will include adding load to the traces by humans pulling on a rope connected to the end of the tugs.

When the horse is relaxed, the helper and the driver agree that the second drive for this horse will be three steps long. Again, the helper stays in front of the blinders where the horse can see him. As the horse’s first foot moves forward we start to count. As the first foot moves forward again, we count step two and watch that head position.

In nearly all of the horses I’ve worked with, the head will come up into the worried position between step two and step three. When that first foot moves forward the third time, we count step three and command the horse to stop.

Now we read those body language signs. Most horses will drop their head to the relaxed position almost immediately. Why? Because they feel we are watching their body language and that we recognize the discomfort they display. When we command the horse to stop, the horse is sure it’s because he asked us to stop with his body language. By deciding ahead of time that we will stop on step three, we let our horse gain confidence in our ability to keep him comfortable! Pretty neat, eh?

When the horse shows he is relaxed again, the helper and the driver agree that the third drive for this horse will be five steps long. And again, the helper stays in front of the blinkers. At the driver’s command the horse will start his first step. We start counting. “One” . . . “two” . . .

During the third step, we usually see the horse raise his head to the “I’m worried” position. We watch that head position carefully while we count . . . “three” . . . “four.” If the horse has confidence that we are there to help him with his worries, he will drop that head during the fourth step. When we get that foot moving forward for the fifth time, we count “five” and the driver commands “whoa.”

Why We Stop At Step Five

If the horse did not drop his head during step four, by stopping at step five we have reassured him that we are watching his language and we are there to help him if he is worried. Therefore, we stop at step five to let him relax. If the horse did drop his head on step four, then he is showing us he is ready to go on with this sport of driving. Therefore, we stop at step five to congratulate him and celebrate his courage. It’s a win, win situation!

If the horse does not drop his head at step four, then we continue to take five steps at a time, always watching the head position and other body language to let the horse tell us during step four that he is ready to drive for more than five steps at a time.

If the humans in this picture fail to read the body language of the horse that tells them the horse is uncomfortable, and if they continue by asking the horse to pull more than five steps, step number six is usually very fast and nervous. Step number seven is usually twisting off sideways and bumping either tug strap with the back legs. If they haven’t gotten the young horse to stop by now, they may be witnessing the beginning of a runaway.

After A Relaxed Series Of Five Steps

After we see the relaxed horse language, this first drive can then continue for 20 or 30 minutes.

During this first drive the helper on the lead rope needs to stay visible in front of the blinds for nearly the entire time. During the later part of the first drive, the helper should pick a long straightaway where the horse is pulling steadily and comfortably.

While walking on that straightaway, the helper should slow down his pace so the horse will begin to pass him. At a point when the helper can no longer see the eyeball of the horse behind the blind, begin to match the horse’s pace again. While walking in that position read all the body language to verify the horse is still comfortable even though the helper has disappeared behind the blind. If the horse begins to show discomfort, the helper simply steps forward until he can be seen in front of the blinders again, and then continues walking on, to give the horse a working buddy again.

Turning their first corner is the next thing to possibly set the horse to worrying. Watch that body language, and if the horse raises his head or shows other worry signs, command “whoa” and tell him you are watching out for him. Let him relax and try that turn again. If you read his signs and stop and let him relax each time he gets worried, you are teaching your horse to stop and stand when something worries him rather than choosing the flight response. What a great thing that is!

Use One-Three-Five Every Time You Hitch To A New Vehicle

When the time comes to hook your driving horse to any new vehicle, your first drive should be one step long. Even if your horse is accomplished at pulling the two-wheeled cart, the first time you hook to the sleigh or the four-wheeled vehicle, that first drive should be one step long. By doing this you let the horse feel the pressure on the breeching with very little vehicle momentum to stop. That’s a good thing.

So get that ground work solid and repetitious, get your helper lined up, and take that first drive. Make it one step long and you will have many enjoyable hours and years with your new driving horse.

Some Comments About Wrecks

Steve: In the driving horse community it seems that nearly every person we talk to has knowledge of a runaway driving horse or a wrecked vehicle. Many of these people do not have first hand experience, but have seen the results, or maybe even watched a runaway horse in action. Being involved in a wreck can be a catastrophic situation for the human as well as the horse, not to mention the vehicle.

Runaways can happen for an uncountable number of reasons. It can be equipment related, such as an incomplete or too light of a harness. It can be that a vehicle chooses an inopportune time to breakdown, such as a tongue breaking, or a tire blowout. These types of wrecks are usually the kind where the driver in hindsight can say that they just didn’t check the reliability of the equipment before hitching the horse to it. Many times runaways involve an inexperienced horse that cannot process all the inputs that he is being asked to work through at a given time. That is why we take such small baby steps in training the driving horse.

The most common reason for a runaway is that the driver and horse have lost communication with each other, leaving the horse to feel abandoned, and the horse will then let his natural flight instinct take over. Remember that communication is a two way transfer of information between two minds. Since the horse cannot talk in the human’s language, it is the job of the human to learn the horse’s language. The horse will always tell us that they are worried about a situation if we are watching their body language. If we miss the information that the horse is telling us, we will not respond with a reply that can set the horse at ease again. We need to learn this body language before the horse is hitched to any vehicle. There is an abundance of information available today dealing with learning and understanding horse body language. Driving horses requires us to monitor that language a distance away from the horse and to then send a communication back to the horse via the lines, or our voice, and most commonly a combination of both.

Once a horse has been involved in a runaway situation, it is difficult and many times impossible to get the horse to again accept driving as a vocation. The rehabilitation of a horse involved in a runaway is an entire article in itself, but suffice it to say that rehab can take 3 or 4 times longer than training from scratch. Even at that point the rehab horse can be difficult to trust outside of the familiar setting where the rehab takes place. Then, you and the horse will always have the memory of the previous runaway in your mind waiting for an unforeseen trigger to set off the next runaway. It takes a very determined, yet kind, human to get the horse to relinquish leadership back to the human after having been involved in a runaway.

Doc: Because of my life-long passion for driving and full-time occupation of teaching people about driving and working horses in harness, I’m acutely aware of the multitude of behavior problems and safety issues that can and do occur with driving horses. Being in the business as we are, Steve and I get calls, emails and letters from horse people who are experiencing success or having difficulty and in need of help. We hear about the mishaps and the tragedies — just recently, a lady in Wisconsin died after a runaway, and a five year-old girl was knocked off her saddle horse and killed by a runaway team in a Texas parade. It’s more than a bit unsettling to clearly understand why such things happen and how they might well be prevented, and at the same time be aware of how common it is for people to unconsciously or unnecessarily put themselves, others, and horses at great risk.

Everywhere I go I experience people asking their horses to do things, accept things, and put up with situations that the horses are not adequately prepared for. Typically, these enthusiastic, well-meaning folks don’t understand that they are asking too much of their horses. Many don’t have the horse communication skills and depth of knowledge and experience to realize that something is not working for the horse(s) — even though the horses always tell us. Others are so focused on the goal they are intent upon (parade, horse show, hitching to a new piece of equipment, driving down the road, giving friends a ride, etc.) that they ignore communication from the horse(s) that says, “This is too much for me,” “I can’t handle this,” “Get me out of here.” Maladjusted, improper, and unsafe equipment is another big issue.

If it was not for the extraordinary adaptability and tolerance of horses there would be far more runaways and wrecks than there are. Most problems arise because of our failure to thoroughly understand horses, our failures at communication with them, lack of attention to details, and asking horses for too much, too soon, too fast. Many, if not most, horses in all disciplines have serious deficiencies in their relationship of trust and respect with humans, in their willingness to accept a human as their supreme leader, and in their basic foundation of learning/education. Even more so than riding, attempting to drive horses with such shortcomings is a recipe for disaster. I feel we must take responsibility for these things and not blame the horse(s). Whatever happens is never the horse’s fault, but rather my fault.

Too often our emotions, requests, and behaviors make no sense to the horses. Each time a horse’s trust in us is violated (damaged) it becomes harder to regain. Each mishap or wreck with a horse, whether physical or psychological, damages their trust in the human (leader) that failed to take care of them. Prevention is the only truly successful way of dealing with a wreck — everything else is just damage control and/or a salvage attempt. Horses NEVER forget, especially if fear or pain is involved. One of the most important secrets of preventing wrecks is to not ask horses for too much, too soon, too fast. Always pay attention to what the horse is telling you and act on it sooner rather than later. By learning to recognize mild concern or slight anxiousness in our horses and acting to defuse it immediately we can prevent it from escalating to the more dangerous stages of confusion, upset and fear. Comfortable, relaxed horses that feel safe do not blow up or have wrecks — it’s our job to keep them that way.

Final Comments

I have been questioned (even criticized) about my slow, gentle, repetitious approach “taking too much time” and all the little steps being unnecessary when one can simply “hitch ‘em tied back to a well-broke horse they can’t drag around, and just let ‘em figure it out on their own.” For thousands of years horses have been trained (educated) using both approaches — by gently and patiently helping them choose to accept and become comfortable with their work (partnership), or alternatively by using force and punishment to cause them to work in spite of their concerns and fears (slavery). I try to give horses the same consideration I would like if someone was teaching me how to do something new and strange. Furthermore, most of the folks who choose to learn from and consult with me are not necessarily seasoned teamsters and I find that they are more able to use my approach successfully without exceeding their abilities and getting into trouble. Many of them don’t have a good, experienced teamster to help them or another well-broke horse to hitch a youngster with.

I am in no way opposed to training horses to drive by hitching them with an experienced horse before hitching them single. In fact, that’s the way I was first taught to do it. I know many excellent teamsters who do it that way with outstanding results. In my opinion, it is not whether you first hitch and drive single or as a team, but rather how you do it. What I am concerned about is this: Far too often I see or hear about so called “well-broke” horses that have been trained by faster, more forceful, less sensitive methods — forced into harness and put to work with little consideration for, or alleviation of, their fears. Experienced teamsters can get a lot of work done with them, but they don’t have a rock solid foundation of trust, ground work, and freedom from fear. Typically, they could not pass all the previously listed “tests” I require of a horse before ground driving. Many times they are not ground driven at all before hitching. If they are sold as well-broke to a new owner of limited experience who is unable or unwilling to control them with the accustomed force and punishment, the results are often disastrous. When horses behave and work for us out of fear of punishment they will only do so until something comes along that frightens them more than the punishment they have come to expect for misbehaving. At that point we are in danger of becoming ineffectual passengers on a runaway.

Many horses out there are safe, well trained and ready for whatever, but it is the drivers that need more education, training, and experience to be able to handle the horses in ways that work for the horses and keeps everyone safe. We should all understand that the best horse in the world begins to be retrained the instant someone new takes the lines or takes him home. In my opinion, the great opportunity we all have, and the thing that will help the most with our horses is to better educate ourselves. Additionally, we need to use good judgment about the abilities, capabilities and limitations of our horses, and our own limitations as well.

Hopefully, Steve and I have been able to share some information here that will help keep you and your horse safe and comfortable as you proceed with driving. Training horses to drive is a complex task. However, it’s one we should not shy away from if we are willing to first learn some important basics and proceed slowly and carefully using gentle horsemanship, baby steps and plenty of repetition. If we make only little mistakes we can learn from them without harm. It can be an incredible learning experience for us as well as the horse, and a source of great enjoyment and personal growth.

For more in depth information on training driving horses we recommend: Breaking and Training the Driving Horse (book and video) by Doris Ganton, Training Workhorses/Training Teamsters (book) by Lynn R. Miller, and Teaching Horses to Drive – a ten step method (videos) by Doc Hammill.

Horsemanship can be a delightful, challenging, and endless learning process. It is a pleasure and honor to be perpetually in that process myself, and assisting wonderful people and great horses and mules along their journeys as well.

Be kind, be safe, and enjoy those horses, Doc Hammill D.V.M.

Doc lives in Montana and helps people learn about horses through his writing, workshops, demonstrations, and horsemanship video series. www.DocHammill.com