Don’t Eat the Seed Corn: Strategies & Prospects for Human Survival

Don’t Eat the Seed Corn: Strategies & Prospects for Human Survival

book review of author Gary Paul Nabhan’s Where Our Food Comes From – Retracing Nikolay Vavilov’s Quest to End Famine

by Paul Hunter of Seattle, WA

The accumulated wisdom of 10,000 years of agriculture is surprisingly tangible, portable and available: it exists in carefully gathered, catalogued, annotated and climate-controlled seed banks, more than 1,000 dispersed worldwide. You might wonder why so many, and why so wide-spread. Because they represent knowledge and opportunity vulnerable in not-always-obvious ways — not just to heat and moisture, to vermin, blight and insects, but to the compounded ignorance and violence of social and political upheavals that might not know what to make of these treasures. In the light of recent destructions of historical sites in Syria and Iraq, the slaughter and eating of zoo animals in Kuwait, it is distressingly easy to imagine these heaps of seed spilled out on the ground, left to the fate of all spilled seed, that time will overtake and erase in an instant, leave not a nourishing crumb.

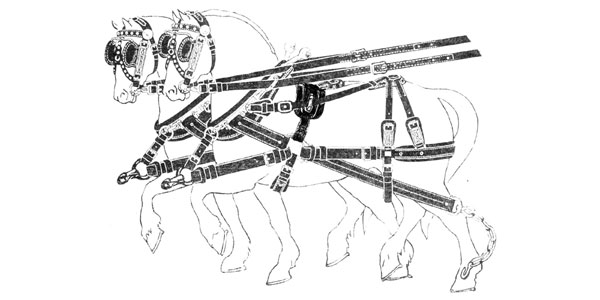

The story of saved seed — and of its parallel efforts in breeding domestic animals — is the story of civilized humankind, a patient story of watching and tasting, of careful choices that encourage some plants over others occurring in the wild biosphere, with the goal of staying put, of making a home. Its effort all along has been the same: to bring our past along with us, to refer and defer to that wisdom, to use past strategies in times of stress to help us feed ourselves. Of course the problems of feeding ourselves cannot be solved overnight, take whole seasons, and must be resolved over lifetimes. The solutions must be far-sighted and flexible. Otherwise in moments of weakness and doubt we might well succumb to the impulse to eat the seed corn and erase our own future.

Gary Paul Nabhan’s book WHERE OUR FOOD COMES FROM: Retracing Nikolay Vavilov’s Quest to End Famine (Island Press, 2009) is a weighty tome, freighted with implications. But as befits its subject it is also portable and travels well, a deft exploration of two trips around the world, that of the author following in the footsteps of a long-gone mentor he never met, the Russian pioneer botanist and geneticist Nikolay Vavilov (1887-1943). It is a complex and modest dance fitting together past and present insights and discoveries, tracing the career of an astonishingly focused and prolific scientist who not only roamed the world collecting seed, fruits and plants and the stories that illuminated them (he led 115 research expeditions through 64 countries, and liked to call himself a plant pathologist), but also, as director of the Bureau of Applied Biology in Leningrad, functioned as the head of thousands of Russian scientists from 1921 to 1940.

Vavilov’s is a spare, skinny story like the seed it espouses, that needs but warm air, moisture and fertile ground to spring to life. But before unpacking Nabhan’s book, it needs to be said upfront that its subject, the accumulated wisdom of agriculture, has been recently threatened with erasure in another way — in the mistaken rush to convenience and the simplistic thinking of industrial agriculture, with its monocrops that are “commodified,” produced and delivered at the lowest possible unit cost, ignoring or discounting the costs and effects of fossil fuel and other synthetic inputs. These monocrops then serve in turn as sources of fuel, and as raw materials for further finished products, often mislabeled as “food” with higher margins of profit than fresh fruits, grains and vegetables. This corporate model with its misplaced faith in GMOs and “Roundup-ready” staples introduces the specter of superweeds which may prove analogous to latter-day plagues like multi-disease-resistant tuberculosis. As a survival strategy, narrowing the genetic options from those millennia of countless informed choices to a few educated guesses made in a lab to suit statistically optimum conditions is a poor bet. Given the volatile weather conditions of the heating planet in just the past dozen years, we can see that extremes of drought and flood, of windstorms, earthquakes and tidal waves, are in our future. We also know that these same conditions, accompanied by crop failures, plagues and pestilence, have visited humans many times in the past, and that what they ate then helped them survive, rebound and prosper. Until recently, the work of farmers to gather and refine seed, cultivate plant and animal varieties was considered vital communal and social work for the good of all. That is, until hybrid varieties displaced those social values with the simpler economic motivation of greed, with its patenting of genetic materials and its peddling of the primary aims of convenience and short-term profit.

But to turn to Gary Paul Nabhan’s inspired pursuit of Nikolay Vavilov. The key idea which drove Vavilov’s restless field research from the first was that areas where crops had first been domesticated were unusually high in plant diversity. He suspected that these places, often mountainous uplands and remote valleys, still contained genetic plant material that had co-evolved with pests and plagues, and had weathered severe conditions such as floods and droughts, so that here he would find both plant genetics and the farming strategies to combat most of the causes of famine. So he traveled in turn to some of the most remote areas on earth, that he labeled “centers of diversity,” to gather seeds and plants, to meet with the farmers there and learn their stories.

Vavilov was uniquely suited for the task. He was a tireless traveler inured to hardships, who was organized and persistent enough to follow the trail where it led. He also had a gift for languages, which he was constantly working on. Before reaching the university he already knew five languages besides his native Russian.

By the time of his last field work he was conversant in fifteen languages, including Farsi, Turkic and Amharic. He thought it essential to record the native names, uses and lore surrounding each sample he collected — as far as possible to place it in its community and ecological, cultural and culinary context. His social skills were legendary: he befriended local farmers, seeking them out in their fields and markets, consulting and treating them as colleagues, noting their responses. And he was a vigorous and original thinker who could express his ideas with clarity and strength. As his colleague N.A. Maisurian wrote of Vavilov’s early 1916 treatise on the origins of rye as a weed among wheat and barley:

“This work had the form of a beautiful etude, describing the ‘original’ history of a famous and widely cultivated plant. He first showed the possibility of applying linguistic analysis to botanical research. After Vavilov… this method was used by [many] other scientists.” (39)

This book shines its lights through layered, compounded and diaphanous viewpoints over time, and achieves some startling effects. For example, in the high valleys where Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan meet in the watershed of the Pang River, part of the fabled Silk Road just north of the Hindu Kush, Nikolay Vavilov had visited twice, in 1916 and 1924, following in the footsteps of earlier adventurers Olufsen and Korzinsky, who had been drawn to explore the Pamirs in the 1890s. But Vavilov’s motive was not adventure, and his work there looks forward in distinctively modern ways that remain useful and relevant, resonating with Nabhan’s visit and its concerns about global warming. Vavilov took the trouble to record the extreme altitudes in these mountain valleys at which various crops could be grown, some of which today are being successfully grown 1,561 and 1,661 feet higher than they had been in 1916. So Nabhan offers a progress report and more: here are not only dire warnings, but measures of continuity and lost possibilities to be rediscovered.

In Nabhan’s hands Vavilov offers a benchmark, a scientific starting point in recent history, toward an understanding of change in the conditions under which our food is grown. The question is, can we catch on in time, not just educate ourselves about what matters, but can we propel ourselves and encourage others to act on what we know. There will be those with no love of the science involved, that although time-consuming, is also complex and elegant. For in its ultimate generosity the plant biology and genetics are at odds with the nearsighted profit motive that has mostly trumped what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature. Nabhan’s close reading of Vavilov’s travel accounts leads to some digested and amplified impacts, where the two field researchers become all but indistinguishable. For instance, Nabhan builds on Vavilov’s deep interest in the naming of various crops, reaching further with his explanation:

“Local farmers had coined their own terms for particular crop species, and, more important, for the new varieties that were constantly selected from their own fields. The mere act of naming a newly found variant of onion or apple leads to its isolation and further selection if the novel plant is given special care by an observant farmer.” (52)

So naming offers the continuing gift of special attention, and an enhanced potential for survival.

Nabhan’s tone throughout is understated, forthright yet mild. Some of the story he tells is of discovery and rediscovery of insights that are ancient, such as the deliberate mingling of diverse varieties of grains together in a field. In such a strategy the proximity of plants with various tolerances for drought or resistance to pests appears to make the shared seasonal ride easier for all. And where pests would be drawn to a monoculture that encourages them to breed and expand to consume the crop, in a field of mixed plantings the pests must pick through a variety that by its very nature works as a maze to resist them.

There is a flavor of diplomacy to Nabhan’s descriptions of what have been essentially international turf wars over natural resources. One of the great opportunities for turning seed not into food but into profit has been the patenting of genetic material as intellectual property. That is one bridge too far, one arrogant step too many for the modest farmer in our midst. This double story is also a primer in what biodiversity means, with regard to the feeding of people. We don’t just need the plants in their habitat, we also need informed representatives who share the 10,000 years of planting, cultivating and harvesting lore in that place.

There is useful, potentially lifesaving information deftly dispersed here. For example, many fields of maize are deliberately grown with teosinte in close proximity, in the highland valleys of Mexico’s Sierra Madre range. Teosinte, the wild predecessor of all cultivated corn, contributes some genetic material to the maize grown nearby, offering resistance to drought and hybrid vigor. And some Hopi farmers in the American Southwest employ a drought strategy of planting corn seed up to 14 inches deep after winter rains, to reach the moisture that will insure a crop. Yet this book is also responsible for unsatisfied cravings. I soon wanted to know how Vavilov managed to choose those places where he led all those expeditions. And on what basis did he select the seeds and plants he collected? At moments I could not help but wish for more. Even telling us the title of Vavilov’s seminal monograph, “The Wild Relatives of Fruit Trees of the Asian Part of the USSR and Caucasus, and the Problem of the Origin of Fruit Trees” (1931), teases us with secrets, with his understanding of why and how fruit trees propagate, touching the question of why apple trees must be grafted to fruiting root stock, and are not grown from seed. Finally I found myself wanting to know even the secrets of human generosity, how early wheat and barley, teff and maize developed in those high remote places ever found their way down to the fertile and populous plains and shores where most humans now live.

Some of the stories of science, of human knowledge, are hard to tell. Often the details overwhelm the reader, and leave him blinking in confusion, at a loss how to digest what he is being told. But Gary Paul Nabhan draws a lightly sketched but real hero out of the past, a gifted, energetic and outspoken ethnobotanist. And the key message of Vavilov’s lifework remains valid to this day — that seed diversity saved in gene banks will protect humans against famine caused by plagues, pestilence, floods, and other natural catastrophes. The unfortunate corollary is that the one cause of famine a seed bank cannot protect us from is the political institutions of man himself, that are capable of magnifying his greed and paranoia, offering unequal access to food, threatening violence, disregarding the nearly invisible sources of knowledge treated like weeds in our midst.

There is a veil drawn over Nikolay Vavilov’s final days and years. He was arrested on August 6, 1940 while on a final expedition to gather seed samples in the Ukraine. He was tried and convicted of a crime against the state — of not doing enough to prevent the famines of 1931-33, which caused the deaths of millions of rural peasants. The actual cause was the official policies of Stalin, collectivizing the farms and confiscating the grains harvested to feed the cities, the army and the bureaucracy. Farmers were not permitted to even till garden plots to feed themselves and their families. Vavilov did not receive a formal defense, and was sentenced to death, but after an outcry his sentence was commuted to twenty years in prison. It is a haunting irony that while serving his sentence, fed a raw mash of flour and frozen cabbage, Vavilov starved to death. The person who had done more than anyone else on Earth to promote and provide food security was denied the means to save himself.

The night after finishing Gary Nabhan’s book I had a dreaming aha moment, as if awakened out of a sound sleep, though still deep in the grip of a dream. There were strangers, visitors who had knocked on my door, and asked “Where are your artists, your musicians?” And from the back of the room someone in my family said, in a cheery confident voice, “Oh, we all do that.” Then, still in the grip of Gary Nabhan’s book about food security in times of abrupt, unpredictable change, I heard those strangers ask, “And where do you get your food from, where are the farmers?” Again came that jaunty answer from behind me, “Oh, we all do that.” Perhaps nothing less will save us.