Home & Shop Companion #0137

Rural Ramblings – Spring 1983

Ralph C. Miller

Pasture

I don’t suppose it would hurt me to confess that I am what might be called an “old fashioned” man. I can hear the snickers out there now. “Why doesn’t he tell us something we don’t know?” As to that, I am only making the admission in the interests of a point I intend to put forth. You should hear me protest in any other case. Conservative, reactionary, hide bound horse and buggy viewpoint, somewhere to the right of Genghis Khan – heaven knows what others outside the family say about me.

The only defense I can offer is one I borrowed from the late Hubert Horatio Humphrey. Late in life, when someone took him to task for a viewpoint that the other deemed less than liberal, he replied that when he had expressed similar views in college, he was held up as a flaming radical. Now for voicing a like opinion, he was accused of being too conservative. He submitted that he was being consistent, it was the ideology that had altered.

It’s hard to stay in the middle of the road when it shifts so rapidly. I assure you that I was very close to the center, if not slightly to the left of it, no longer ago than the 1920’s and early 30’s. It isn’t really my fault that I have trouble staying in step with the 20th century. Maybe if I make an honest effort in the next 17 years, I’ll make it, but I doubt it.

Right there is another evidence of my difficulty with progressive thinking. Some people will take me up on what I just mentioned. The popular nostrum, force-fed to us by self-styled experts is that the 20th century won’t end until the stroke of 12 on December 31st of the year 2000. And they have such cute, pat answers for that foolishness, too.

Anno Domini! The year of our Lord. The calendar they aver smugly, is based on the year one of Jesus’ birth. “There never was a year zero,” they declare triumphantly to prove their ill taken point. They could be right except that there never was a year one either, nor ten or fifty. There weren’t any of the know-it-alls around to mark it down for us, so these numbers only came to us in retrospect. Our current calendar (how many times amended?) came into being hundreds of years later. And the experts of that day came up with a number we are now led to believe was three, four or up to seven years off.

So if those expert nitpickers are looking for a precise moment, we’re probably going to come to 2100 years since Jesus’ birth about September ’97 or ’98. Now doesn’t it make more sense to just finish one calendar century on the stroke of midnight, December 31st, 1999 and start the new one in with the year 2000? I know that’s what I intend on doing. Yes, I expect to live that long!

Well, I guess that confirms my basic admission that I am old fashioned. Given that premise, as you might expect, I quote my scripture from the King James version. Everybody’s favorite psalm contains the passage: “He maketh me to lie down in green pastures, He leadeth me beside the still waters, He restoreth my soul.”

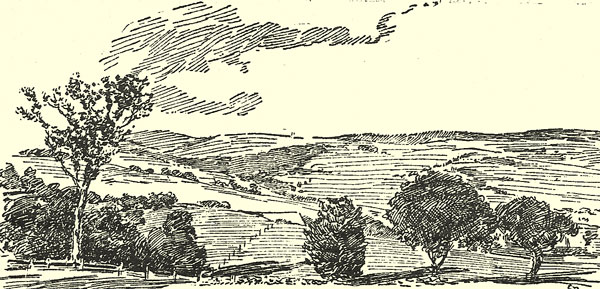

Yes, you are right. All this round-about meandering has finally brought us into the pasture, where we were headed all the time. Pastures (green pastures, as indicated by David, psalmist, King and quondam shepherd boy) were a major part of agriculture back in early Biblical times. Indeed, it is possible that pastures had as much to do with the spread of civilization, the alternate growth and sack of tribes and nations, and the development of life styles, as any other single thing through pre-history and down, at least, through Biblical days.

Reindeer man in Northern Europe, ten thousand years ago, followed the migrations of herds. At what precise point they evolved into the Celts and other early people who began following “greener pastures” with the animals they had domesticated from the wild cattle herds, we don’t know exactly. It was probably a gradual development and cattle and herdsmen alike moved South and East through the Balkans, the Grecian peninsula and ultimately to the near East. Father Abraham was only one of the Patriarchs whose tribes drove herds into one new area after another. Peaceful movements at the outset, they eventually led to territorial wars. That same Genghis Khan I mentioned was at the start of a relatively peaceful dispute over horse pastures on the Mongolian uplands. Though not so acknowledged, it eventually became the first true world war, spreading from China on the Pacific all the way into Central Europe and as far south as North Africa.

There is no doubt that pastures and the search for them has had profound historical effect. Even in early times in America, tribes followed the migrations of the Buffalo herds. (Yes, I know the proper scientific term is Bison – it’s just that ‘Oh, give me a home where the bison roam’ doesn’t have the same ring to it.) By whatever name, those vast millions of shaggy beasts were the lodestones by which tribal fortune rose and fell. And the herds followed pastures.

As buffalo diminished and pastures flourished, cattlemen took advantage of the open range. The struggles for the control of those virtually unlimited pastures, with all that implied in range wars, sheep wars, barbed wire and the coming of the plowman, would supply an avid Hollywood with plots for more years than actually transpired in those original struggles.

Pastures continue to be important all over the world. Among the most pastoral people, they are often a life and death matter. Only a few years ago (3-4?) the terrible droughts in the Sahel region of equatorial Africa dried up the overburdened pastures and thousands perished as a consequence. The situation is somewhat improved there now, I believe, but at terrible cost. The loss of so many cattle (and people) has lessened the burden, giving pastures a chance to catch up a bit. That is one drastic drawback of good pasture seasons: the buildup of herds, of people and of the consequent increased use of the land; when the bad years come, as they inevitably do, the overburdened pasture gives out quickly. Biblical reference is to “seven fat years, followed by seven lean years.” In many parts of the world, that pattern hasn’t changed much. Some of the world’s great deserts once pastured large herds. It shouldn’t be necessary to belabor that point.

If we think such lessons only pertain to the past, to nomadic people or to other countries, we need to take a closer look at our own pastures. The latin word was “pascere” – to feed – which has come down to us through pastura, into such varied forms as pasture, pastor and pastoral. All these call up visions of serenity, gentleness, the slow and tranquil grazing of animals, tended by careful, caring, quiet herdsmen, in a verdant rural setting.

Sometimes it is almost like that – sometimes! At others – it is no vision, but a nightmare – of half-starved animals frantically overgrazing dried out, dying or dead vegetation with forlorn hope of any restoration or alleviation. Desert in the making. Fortunately most pastures fall somewhere in between.

Pascere – to feed – if our pastures fail to feed, to provide all the nutrients necessary to sustain the animals we keep, they aren’t true pastures and we are failing as pastors. All through the Old Testament, the analogy is drawn between our responsibility to our flocks and our relationship to a sympathetic but exacting Creator. It is a necessary assumption, for just such responsibility exists. The day when we could turn herds or flocks loose to find their own forage is no longer at hand for most of us.

I recall from my long-ago student days that one general division of pastures was the improved, as opposed to the native or unimproved. There are still areas where farmers, ranchers, drovers or herdsmen – pastors all – can run cattle or sheep on relatively unlimited acreage of unimproved land where sufficient grazing and/or browse will be found to provide the animals with adequate forage.

For many more, perhaps for the majority of such herders, it is necessary to rely on the so-called improved pastures. (I say so-called since it is my contention that many improved pastures have much room for further improvement.) These are fenced in areas where the herbage has been intentionally grown as provender for animals. Such pastures may be permanent, temporary or conditional; i.e. designed for other use ultimately but serving meantime to feed the flock – as hay fields or grain fields in early spring or cover crops used for grazing before being plowed under or harvested. A third division is the annual pasture which, as the name implies, is a crop designed for one year’s pasture only, perhaps while a permanent pasture is being planted or renovated. Annual pastures are often one single year of a crop rotation.

If sufficient nutrients are present either naturally or added through judicious fertilizing, liming and the wastes of the grazing animals, then the pastures will continue to feed – “pascere.” Somehow, perhaps we take pastures too much for granted. We’re fond of that vision – fat cattle grazing on those “green pastures,” perhaps “beside the still waters.” The grass is unlimited and all-sustaining, and we have only to allow the animal to get to it. Alas, pretty as the picture is, there are too many of our readers who know how far it falls short of reality.

Not that “lying down in green pastures” isn’t an enviable hope, or at least a comforting dream. I can remember long ago as a small boy (one of the blessings of growing older is the penchant for only convenient memory – very selective), thinking how fortunate were the cows. The summer pasture was not only the source of their favorite food, it was dining room, living room, and bedroom all rolled into one (not to mention necessary room too, of course). It provided a soft bed for them to lie on, a shade from the hot sun, and the brushy patches scratched their itches and helped brush away the flies. I admit I never asked for their opinion of this, and they, of course, volunteered nothing. I don’t know if they would have liked to swap.

They never came in my house, but I spent a lot of time in their barn and more particularly in that pasture. The shade and the soft grass were an attraction, as were the flora and fauna of the pond where they drank. About the only thing I didn’t really envy them was the grass they ate. It just didn’t taste as good as they made it look.

The lower end of the pond sort of disappeared into a swampy, cattail and reed-grown area, where snapping turtles, frogs and the elusive shitepoke or bittern coexisted after a fashion. At a very early age – not yet 5 years old – I would sometimes be sent (for sent, read allowed) to the path that led down along that end of the pond of a summer evening to bring in the cows. I always felt very puffed up with my own importance and responsibility. The plain truth was that our exceptional stock dog ‘Gyp’ was actually fetching the cows (and me too). She did it by herself most of the time anyway. When I was along, it was just one more to look out for.

During high water, spring or after hard and continous rains, the pond would rise and that trail would be part of the bog. The cows didn’t mind, and often neither did the small boy – although his mother didn’t always appreciate him coming in with mud to the knees.

I knew that pasture well, probably twenty-five acres of the unimproved kind with permanent grazing, some brush, trees, a short stretch of creek, the pond, hornets’ nests and an occasional fearsome looking, but harmless, snake. Cottontails skittered from underfoot. Chipmunks chattered from the occasional stump and red squirrels scolded from the pines overhead. I knew where the birds nested, the thicket where the partridge mounted the hollow log and drummed for his mate. Now and then a cow wouldn’t come in with the rest of our small herd; it would be necessary to go and find her. Often when she was finally surprised in her hiding place, there would be a wobbly legged calf nuzzling at her side.

That’s what pasture meant to me growing up, up there in Wisconsin. A rather idyllic and stylized concept, I admit. I wouldn’t be too surprised if there are still a good many folks who may still have a similar idea. I know now that it wasn’t all that good nutritionally speaking, although at times the growth was luxuriant enough, especially in spring. The soil was too sandy and undoubtedly too acid as a result of the pines and no added lime. It couldn’t have had the food value to make the best milk or growth in animals, although none went hungry. The cattle would occasionally browse on the tenderest young brush and other plants. That was an indication that they were seeking better nutrition and the trace minerals brought up by the deeper rooted plants, trees and bushes.

Incidentally, if your cattle are eating leaves or stripping bark from trees, you probably should have the soil tested for those trace minerals. They seem to know by instinct when they aren’t getting enough zinc, iron, magnesium, cobalt, copper, iodine and such other minerals as they require.

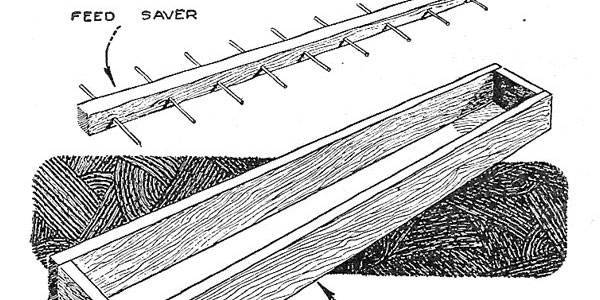

I suppose what all this means is that we are missing the boat in so very many cases in our pastures. We raise animals, livestock, for various reasons and after 8000 years have much to learn about the true advantages of pastures. The nomad of that early day simply kept flocks and herds moving, following the best natural grazing to be had. We ought to have learned better than that, and some surely have – but not all of us. After all, any study, not to mention the application of common sense, will tell us that our stock can be nutritiously fed on pastures at half the cost of other feeds, such as hay, grain or silage. In most parts of the country, this can be true for six to nine months of the year.

That’s a practical consideration, but there is more, too. Any stockman of judgment can tell us that pastures are a great corrective. The stock that has suffered from poor feeding practices, lack of fresh air and too close confinement through the winter months literally blossoms in the first weeks back on pasture in the spring. It is the healthiest, most natural environment for animals. With all that, the savings in feed costs, in healthier animals with lower medical bills, it only makes sense to expend the comparatively small cost and effort to make pastures what they should be.

Pastures take so much less care proportionally than a corn crop, say, or a grain field, and yet there is that two or three to one ratio of time that pastures do sustain the animals, why do you suppose we so often neglect even that minimum of care? We need to provide some additional fertilizer, we should harrow the permanent pasture acreage once or twice a year at least, and if there is any of it that isn’t fully grazed, we ought to mow it to stimulate growth. If it gets enough moisture along with that, it will not only thrive, but the improvement in the livestock will be sure proof that this effort has not been wasted.

The single most important need of most pastures is added calcium. Soil testing IS important and the pH shouldn’t be allowed to drop below 6. A 7 (or neutral) is even better. Sufficient calcium in the soil is essential in breaking down and making soluble the other elements, phosphorus, iron and even nitrogen. It makes the soil more friable, aids in water retention, acts as a wetting agent, helps form humus and is an all-around soil conditioner.

What the element itself does in animals should be so readily recognizable as not to need too much emphasis, but since we’re rambling already – if you’ve ever been to Lexington, Kentucky, I don’t have to tell you that the city is hemmed in by horse farms. I was a little awestruck. I had heard of them surely, but until you see them, it’s hard to envision the sheer volume. One of the major considerations involving the establishment of the operations there is the amount of natural limestone in the soil. It makes the bones that absorb the shock the race horse puts on his anatomy.

Driving south on US 441 just a few miles above Ocala, in Florida, you pass an old, abandoned limestone quarry. As you breast the hill, laid out before you is another ‘Lexington’ on a smaller scale. Horse farms both sides of the road for more than a mile. We don’t have that type of operations here in Oregon, but over beyond the Cascades in the John Day valley, there’s a region noted for its high limestone content. Cattle thrive on the pastures and hay from the valley is prized. There are numerous such regions in the country so blessed, but if yours isn’t one of them, then by all means add a ton or so of ground limerock (much better than hydrate of lime) to the acre every two or three years.

At least five to ten tons of animal manures per acre, with perhaps some super-phosphate (about 40 pounds), will keep that pasture in good shape. This ought to go on at a time when the animals are not on this particular pasture. (Fertilizer is fine on my strawberries, but not when I’m about to pick them, if you please.) If your manure supply is insufficient, the addition of a good balanced commercial fertilizer may be advisable.

The other thing we mentioned briefly was harrowing. Even native pastures, where some stumps, trees and/or stones may be present, could profit from being worked over with some type of drag from time to time. It breaks up thatch, divides the stools of grass clumps so that they spring up more thickly and with renewed vigor. Dragging or harrowing also breaks up and more evenly distributes the droppings of grazing animals. Moisture is always retained better in pastures after occasionally being worked over.

Along with the harrowing process, you should consider whether judicious reseeding would improve the herbage. Grasses and legumes grow at different rates and different times of the season. A variety of several such plants extends the pasture life, increases palatability and will be more suitable to varied climatic conditions. Some will say that pastures ‘run out’ after some years. That isn’t true – it’s only a reflection of neglect.

If we seem to be building some bovine Eden, be assured that there are serpents lurking there. Weeds mostly. Pastures are notorious havens for weeds. Permanent pastures are so seldom worked to any extent and most weeds tend to thrive on neglect. Thistles, wild rosebushes, blackberry vines, thornapple, along with palmetto, spanish bayonet and a whole host of thorn armored vines and brush in some southern states, all make their presence felt if you have to amble through the brambles, but there are many others just as noxious, if not so spiny. And there are toxic and poisonous ones as well. Some thistles qualify, as do sumac, loco-weed, any number of plants native to various parts of the country – including locally a deadly little number (mis)called Tansy Ragwort.

I’m often accused of being critical of the scientific establishment, but this is one of my personal peeves. Totally unscientific as I see it. Tanacetum Vulgare – Tansy is a yellow flowered herb, probably not native, but often domesticated, which your grandmother (should that be great-grandmother?) might have used as one of her ‘simples.’ A febrifuge, a worm medicine (in combination), sometimes a specific, but often an all-around tonic. It was a mild stimulant, but in no way toxic.

Senecio Jacobaea, Tansy Ragwort, on the other hand, although also yellow flowered and a roadside plant, is highly toxic and often fatal to some animals, such as horses and cattle. All this is admittedly true, although I deplore the action of tacking the name of the inoffensive, totally unrelated Tansy on just to distinguish this type of ragwort, simply because of a fancied similarity in the blossom and/or growth habits.

The thing that really offends me is the mistaken habit of the agricultural press and the (supposedly scientific) Agriculture Extension Service, to shorten the name of the poisonous Ragwort to Tansy – even in their control broadcasts and brochures. Grandma ought to sue! Well, Tansy Ragwort by whatever name, along with all the others, should be eradicated from pastures on sight. Some animals may be able to distinguish between good and evil vegetation, but you shouldn’t leave temptation in their way anymore than you would leave the arsenic bottle on the table next to the saccharin.

You thought all pastures were peaceful and idyllic? Not exactly – ask the shepherd. Wolves, coyotes, bears, cougars – tigers in India, jaguars in Central and South America. Even alligators and crocodiles are hazards in some pastures. Not even the skies are safe. We’ve always known of the potential threat of eagles and other raptors; now we have to be conscious of acid rain. How terrible is man, that dares pollute even the Bard’s ‘gentle rain from heaven.’

Are you downstream from some modern marvel of technical manufacturing efficiency? PCB’s, radio isotopes, toxic chemical wastes – or even the run-off from your own or the neighbor’s pesticides and herbicides! And our small boy long ago had only hornets’ nests and an occasional garter snake to trouble him. Careful, lambkins – it’s a jungle out there!

Maybe we can digress a moment – it will tie in, I promise you. The ancient Greeks are credited with the discovery that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Of course that seldom applies to such ‘Rural Ramblers’ as small boys – and cows. There’s a natural caste system in the herd, a pecking order. Usually the social arbiter, the leader, is some hefty grande dame of a cow full of years and her own importance. In long established pastures, the routine is set, but turn the animals loose in fresh pastures and our leader will make the trail. They may well all graze at will on the way out, but when it’s time to head back to the barn, the watering trough or the salt lick, they will obediently fall in behind our heroine.

With her calm eye fixed on the main chance, she will probably head in the general direction, bell ringing, bag swinging, but not exactly as the crow flies. Like an old time caravelle in full sail, she’ll tack her way across the expanse of pasture, now to starboard, now to port – and often for no reason visible. Of course the herd follows and the new trail is set. Thereafter and forever, even though the herd leader may change, they will all follow that path or until new barriers force them out of it.

I expect you have heard the tale of how one of the good burghers of New Amsterdam first dispatched his herd to the upper reaches of Manhattan Island for summer pasture. Following the leader where she wandered, they made the trek. And all the subsequent herds only deepened the path. In time some of the owners visited the summer pastures – by cart or carriage, as befitted men of such stature. The cow path became two ruts, rather than one and as was the custom, was referred to as ‘the broad way.’ Although it is now the famed street of broken hearts and bright lights, the last time I drove it some six and a half years ago, Broadway was no straighter and very little smoother than the cowpath established by that long forgotten bossy on her way to the pasture.

Well, I said we’d tie it in, didn’t I? We were talking about the problems inherent in pastures. We didn’t mention soil erosion. If your pasture is flat, it likely won’t trouble you, but so many are not. Cowpaths soon become ruts, and on slopes that can present real potential for trouble. Rains and run-off so well appreciate cowpaths that they genuinely and literally often become pitfalls. The best cure is prevention. Some barriers or an induced slalom course is indicated for such a case. Get Bossy to vary her passage to lessen the impact on the pasture environment. Brush piles, rip-rap rocks – they’ll not only help convince the cows, they’ll serve to catch the washing soil and fill any already committed damage.

We were speaking of the trials of shepherds back there (notice we didn’t even mention anything about the Dugway Proving Ground disaster in Utah a few years ago). A good many folks around the world are still following the ancient calling of pastor in its earliest meaning. The Basque shepherd of the Pyrenees and our American West is traditional, but the practice is not limited to that. Men, boys and to some extent girls and women, still herd goats, sheep and cattle, usually to higher pastures in summer to save the lower fields and meadows for hay and for the time when weather forces them down. If one is temperamentally suited to that life, I can imagine it can be rewarding. Most of us are too impatient to stand and watch grass grow and goats graze, but if solitude and contemplation of the universal verities, along with a full-time commitment for those relatively helpless creatures is motivation enough, then shepherd, goatherd or cowherd is a calling you may be fitted for.

There are other aspects to it: in Mexico, Puerto Rico, in the Netherlands and in Spain, I have seen shepherds graze their flocks along the roadsides (narrow crooked roads and little warning – that can make for some interesting moments for the unwary motorist, as well as the shepherd). But I have often mused over the waste of squandering this not inconsiderable vegetation where we burn it, mow it and/or spray it with herbicides in our country. Of course, after it has been well polluted with auto exhausts, it may not be the healthiest forage anyway.

Back in the spring of ’78, I gave mention to Sunburst Farms and a program they had on with the Forest Service (I believe they have since sold out and moved to Utah or someplace). At that time, they maintained a goat camp for 1800 goats in the Los Padres National Forest of southern California. Some of their people, in rotation as I recall, would herd their large flock of goats carefully along fire lanes and mountain tops. By keeping vegetation down, they tended to alleviate fire danger and helped in control if fire did break out during the hot and windy seasons. That’s a modern and innovative use of the ancient art of moveable pasturing.

It has been going on for thousands of years, so you may wonder why my sudden interest in the subject. It could have something to do with a practice that led to a fairly universal expression. When an animal that has served well is too old for other useful purpose, humanely we often put him out to pasture. Perhaps at my time of life, I am somewhat painfully conscious that the expression, and the practice, are not limited to four-legged animals.

Then, too, I do Ramble, and as I pass around this varied land, fat cattle in good pastures make me happy. Conversely, I am saddened by the sight of too many lean and hungry creatures on parched and meager acres. Especially when it’s all so unnecessary. Good pastures aren’t that hard to maintain and pay rich dividends. ‘Green pastures’ take a good and faithful pastor. And at sight of them, this old Rambler can ‘restoreth his soul.’