Old Man Farming

Written by SFJ editor and publisher Lynn R. Miller, Old Man Farming: Essays of a Rewarded Life is a book to add to your summer reading list. Here is an excerpt of a chapter to whet your whistle.

what it takes…

Some will remember how it was that Dad never explained, just expected you to know. “No, not that way. To the left, to the left! Haven’t you been paying attention?”

Instruction was a ludicrous concept. Water in the nose, fire on the skin, ridicule in the gut, dizzy with pain, nauseous with anxiety, dull with confusion; these were the ways to learn. Those days, for some they may still be today, if you didn’t allow yourself to be pulled along you were left behind. And behind was nowhere, no flow, no connection, no justification, no ladders, no doors, no coupon, no pay, no stay, no return.

“Why would I waste myself explaining to a kid or a greenhorn how the thing is done? It’s an invitation to questions, the answers to which invite more questions. The work doesn’t get done that way. And the kid doesn’t learn that way. They either pick it up or they are out of here! Forgiveness and understanding never got the pig cut and wrapped.”

I wonder if this ‘tough it out’ message isn’t a main reason why so many of us farmers are fiercely independent?

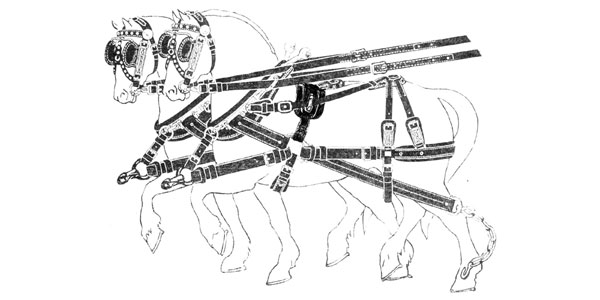

“Nobody held my hand when I learned to work a team.”

Hard to argue with those sorts of valuations of resilience and self-sufficiency. I certainly came from that. But I’ll try to argue nonetheless, because today so many are desperate to know what to do. The collective memories of that other great depression frequently suggests that it took toughness and self-reliance to survive when all else failed. But there is also ample evidence of how it was that communities working together made a very great difference in hope and possibility. Or how ‘extended’ and deep-rooted family held together faith.

Bad days at the bank, sad days on the edges of the river. Millions of good people in this country and others have found themselves in the very depths of economic and emotional depression. It has begun to dawn on those of us who thought ourselves immune, resilient, self reliant, that this minus tide IS taking down ALL boats. No amount of pretending, no amount of analytical gymnastics, hides this terrible fact. But that doesn’t stop the opportunistic merchants and priests of denial. Why do I make these observations at this time? What possible good is done by pointing out the painfully obvious? I believe to my core that amidst this depression one of humanity’s greatest enemies is alienation, I don’t mean as in those protectionist tendencies that alienate countries and cultures from one another (bad enough those), I’m speaking of the close-in alienation that breeds unhealthy suspicions and distance between individuals.

“Keep them away. Their problems aren’t ours. We’re clean and strong, they’re living on the river’s edge in a tent. We aren’t like that, we’re clean and strong.”

Wrong. Their problems ARE ours. And you know what? If we could believe that, really act and believe as though we are in this together, their problems would lessen AND the tide would turn. It has nothing to do with commerce, with spending, with government largess. It has EVERYTHING to do with TRUE community. Nothing to do with handouts. Many people know this and act on it daily. The river’s edge is peopled not just with the homeless, it is also regularly visited by folks who care and, regardless of their own personal well being, folks who will stop at nothing when it comes to helping those suffering human beings within their ever widening view.

At the same time, within the wider agricultural community, there is a stiffer, longer held tradition of alienation buried deep within the most ornery and tenacious of farming’s survivors. Some might take offense at my choice of words and prefer to call them fiercely independent. While they are definitely that, I will add that some of those folks bring upon themselves by choice and consequence a very real alienation from other individuals and community effort. But for this discussion I would point out that this world of farming’s independent survivors is a parallel universe which measured against today’s depression shows a curious pattern of weaving trajectories. A pattern which may show us what it takes to build acceptable and revitalizing community.

Long after his physical capacities have dwindled to pain and stiffening, what drives the solitary old man to continue bringing in the handful of Guernsey cows to milk? To laboriously split the piles of perfect kindling and stack so meticulously in the perfect woodshed? To struggle with the anxious young horse in tedious repetitious harnessing? To calmly shoot dead the helpless suffering cow? To stoop and pick the wild flowers for his lonely breakfast table? To disassemble the hydraulic pump for the fourth time, carefully replacing the o-ring? To scratch with pencil stub at the scrap of paper, planning a new cross fence he may never be able to build?

After all, this man does not worry about getting a piece of land to farm, he is beyond that. And this man does not worry about family as his wife is dead and gone and his children are far enough away in their own anxieties and longings to be disconnected. And he does not worry about learning how to farm, something that he absorbed in his dirt-fighting youth. Pulling a red hot chunk of steel from the forge fire, or pulling a struggling calf from its young mother’s uterus, or pulling hay from the mow, or pulling five dollars from his wallet, he doesn’t think much about making his farm pay, that’s behind him now. Eighty-five years old, he doesn’t think about not having a retirement account or health insurance. If he worries it is about his cows, who will care for them when he wakes up dead? If he worries it is about his land, who will know what to do with this fragile piece of the planet? If he worries it is about his tools and what they evidence. Who will know how to use the device he invented to pull stuck posts out of the ground? Who will know how to spin the drill press head before starting the motor? Who will forgive the old millstone its dips? Who will keep the wooden handles of his screwdrivers oiled? Who is there to honor the craftsmanship he cultivated for nearly a century? For the only honor craftsmanship can use is that which carries forward with the working.

What pushes the lonely old woman to continue the working of her ramshackle ranch? To stitch together, one more time, the tired corner rock crib? To gulp cold coffee after breathing the ammonia-soaked feed dust of the poultry shed? To shoot dead the errant dogs and bury the tortured pieces of dead lambs? To siphon gas from the tractor to put in the pickup truck? To jack up the long heavy gate and balance for one half hour of juggling frustration just to get it lined up to fall back on to its hinge bolts – a job that could have been done in 20 seconds with one additional pair of helping hands?

After all, this woman owns all of this land. She could sell it tomorrow and live worry free for the rest of her days. Her physical aches and pains, her increasing limitations are each and every one met with the internal shrug of unquestioning dedication and ownership. Even so, she’d love to have someone to share the cold morning sunrises with, someone to laugh with and complain about. Someone who never got in the way and had sense enough to keep wood in the fire. Someone who watched and learned without needing to be taught. Otherwise who will honor the craftsmanship she has cultivated for nearly a century? ‘For the only honor craftsmanship can use is that which carries forward with the working.’