Spinning Ladders

Spinning Ladders

by Lynn R. Miller

“In the dream, I was climbing a wooden ladder of my own construction. Carving and inserting rungs into the slow-growing parallel upright poles. I drilled the holes for those rungs with my thumbs. I chewed the ends of the rungs to created perfect tenons. The background music alternated between the bleating moans of a large old dog and the sweet and sour trumpet-like urgings of grasses and legumes working their way up through the wet and dry earth. Out around me, some distance away, I could see others building and climbing their own unique ladders of various height. They would not see me, they would not hear me. I had a growing sensation that my ladder was near completion and sure enough it tipped to one leg and started its slow elegant spin. It was spinning in the wind of all my hopes, realized and not. It was then that I became aware of an urgency I had worked so hard and so long to deny. Looking across that landscape of ladders, I saw some growing and some spinning and many falling over with their builders, only to disappear completely. But I also saw a few in clusters, standing and waving rather than spinning. I wanted my ladder to be in a cluster, I wanted my ladder to wave into the future, but I had waited too long.

I suppose you could apply that dream in many ways but at this time of my life I cannot help but think of it as a subconscious concern for the future of my efforts. Some might see this dream as the lament of a hermit who wishes to rejoin society. Others might choose to think of this as a man’s reflection on his legacy, but I don’t feel either. I feel a genuine concern for the ongoing, well past me, and past any signature I may leave behind many years from now.

The main portion of our ranch sits in a remote rock-rimmed wide canyon the indigenous people referred to as the valley of the stand-and-look-at-you-deer. It is sacred burial ground for at least one native nation. It is the home to the largest mule deer winter habitat in the world, home to elk, cougar, eagle, turkey, kestrel, redtail, chukars, and summer home to swallows. Surrounded by forest service land, we are on the lip of the Metolius Basin. It is the sage, pine and juniper-scented, water and feeding center for a vast habitat extending from the Deschutes River canyon to the Mt. Jefferson Wilderness area to the rapidly encroaching developments of the neighboring towns to the south and west. And it is where we try to farm. As one of the last remaining small family ranches in the area, the pressure is on, through taxation and market urgencies, to subdivide and develop. We don’t want that to ever happen. Not just during our tenure, but far into the future. We look for the best steps we might take to find a legal designation which will give the area a quasi-public, sacred, park-like protection. We don’t seek to protect it for ourselves, or even for the general public, we seek to protect it for itself. This effort is like one of those ladders which would stand, spin and wave long into the future, long after we are gone.

Farmlands must first be protected individually by individuals. To exempt lands from categories of use through government edict only protects them for future abuse. The best way to protect farmland is to make the highest and best use of that land to be farming and to allow the extended community to embrace it and her famers as sacred to their landscape. You do that as a farmer, as a farm family, as the farm’s community. You do it locally and you do it with religious fervor.

I am reminded that we hold within ourselves so many secrets of the doing here which we take for granted. We know where the water is, where the sun warms the ground first, where the grass is the sweetest, where the elk bed down, and how to read our sky. We remember what crops have failed and which have bloomed. We fondly recall those of our efforts which left the stamp of greatest beauty on the place. When we are gone, what will happen to those secrets? Once again, I believe, unlike the dream, that our time is far from up. I believe we should be working to share all of those secrets with others who might be dedicated to their own overlapping futures with these doings and this place.

I once read a quotation of Edward Curtis, the famous photographer of the North American Indian, which went something like this, “As each of these old people die another piece of their culture dies with them.” His observation, his lament, came in the context of a time when those cultures were, in many cases actually outlawed and certainly dwindling, so the death of an old person likely meant that traditions would also die. For three decades now we have seen the same thing within the community and traditions of true farming. An entire culture which embraced, practiced, and worshipped a farming trust, a way of working which succeeded, and worked better every year, was attacked at every social and economic level. So with the passing of each old farmer, and each old farmer’s farm, we lost pieces of our culture. We lost ways of listening, working, smelling, touching, measuring, tasting, feeling, valuing, and loving. That critically vital way of life is not completely gone yet, each of us holds on to a small corner of it and we have done tremendous good work to keep it alive. But now we must add a broader level of concern. We must attribute to ourselves that same preciousness we once attributed to mentors lost. We have to go into each day asking what it will be like when WE are gone. Now we are the torchbearers. And we need to train and support those who will take the torches from us because what we have saved and built upon is more important that we are. As farmers our cause has been the cause of the peaceable kingdom. I have written before of how it is that I believe the small independent farm is the answer to our environmental woes. Perhaps I should have been adding, all along, that it is also the answer to hunger, deprivation and war. If our peaceable kingdom is to continue to flourish in our small corners, and then move out and into the wider world, we need to see it as our duty to think about passing on what we know, what we care about and what we have built.

There are those amongst us who have been fortunate to have ‘inherited’ their farm and/or their farming. Not just the piece of land with buildings and fences but more or less a way of life and a living fabric of traditions. They have a tangible sense of what it means to be carriers of that tradition. Many of us made the farm and the farming ourselves from scratch. We have a far less tangible sense of things going back before us. We lean on instruments such as this publication (Small Farmer’s Journal) to give us connection to a wider remembrance and solemnity and to give us permission to be thankful for our work; give us permission because we live in a society and time which honors tradition only in so far as it might be marketed. All of us in this far flung community, this sub-culture of small farmers and ranchers feel some measure of regret that what we have built, and are building, feels fragile and transitory; feels like our own short lives, when we suspect deep from within a collective genetic memory that it needn’t be that way.

Each of us will pass on-or pass away. We do have a choice. In this regard, you don’t hear that very often these days. We have a choice whether to pass on or pass away. I am not speaking in a biblical sense. I am speaking in the sense of working traditions. It has taken me a lifetime to arrive at certain precious working conclusions about cattle, horses, soils, and procedures. Over a short quarter of a century I have come, with my volcanic passions unchecked, to fear, respect and love this piece of ground we have been entrusted with, our little ranch. I want, in the most complete sense of the meaning, to pass these valuable things, this culture, on. Not on a given Wednesday, when I might board a year-round cruise ship in permanent retirement (Something I will never do.) You die off by passing away. You live on by passing on. I want to pass the culture of my life on slowly, over the ripening time of my best years.

I woke one morning thinking “I am one who remembers what it was like in my beginning.” Then I jabbed myself with a “Mister, most everyone remembers what it was like in their beginning. There’s nothing special about that.” Fact is I may not be unique in any regard. My story is hardly worth repeating except in its ordinariness. Yes, I may have some gift for stringing words along or for drawing or even for horses, but those are not stories that necessarily link me with you. What links me with you are those ways we meet in our experience. What I mean when I say my story is ordinary is that it is composed of wants and wishes, struggles and triumphs just as your is. We share enthusiasms where we share enthusiasms. We share frustrations where the frustrations are. I might tell you amazing stories of my time with senators and congressmen, but it would bore you because we don’t share that world. But if I were to say that I have a horse who is a booger to trim and that I have figured out a way to get it done, you are all ears. You are interested in my beginning and I in yours. You might be interested in my today. I am certainly interested in your today. My today is a new place for me.

We have built a tall, beautiful and vital ladder which needs a cluster to assure it will stand for the longest time. We are looking for that cluster. And so it is also with our ranch. We are looking for that cluster. I am determined for our farming and our land to be two of those tall, slowly-spinning ladders that stand glowing for a very long time.

This is a new place for me. I feel added dimension to many of my choices and valuations. I liken it, in my own visual thinking, to a relay race. The only difference is that coming up from behind me and all on my team are several runners I am coaxing, ready to receive the several torches I bear. And as I hand them off, at different intervals, I plan to continue running alongside for a ‘far piece’, being a part of the cluster, jumping, as I laugh, from one spinning ladder to the next.”

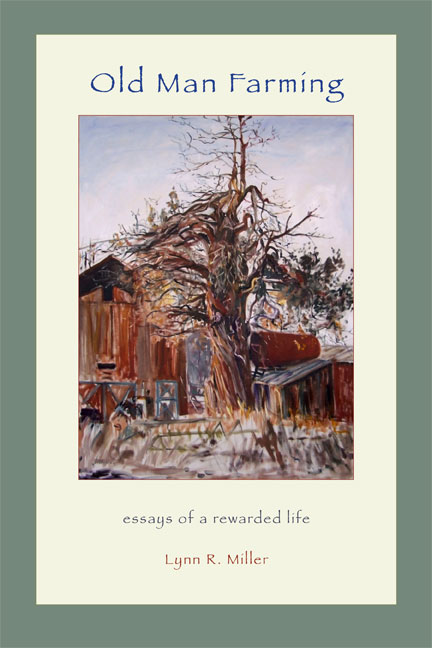

Lynn R. Miller is the editor and publisher of Small Farmers Journal. This is Chapter 8: Spinning Ladders from his book of essays, entitled “Old Man Farming.”